Flavor of the city

Updated: 2011-04-28 06:44

By Christopher DeWolf(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Hong Kong's reputation for culinary excellence has spread around the world. While many of the city's characteristic treats may have originated in other parts of the world, they are made to a standard of flavor and appearance that is distinctively 'Hong Kong'. Christopher DeWolf reports.

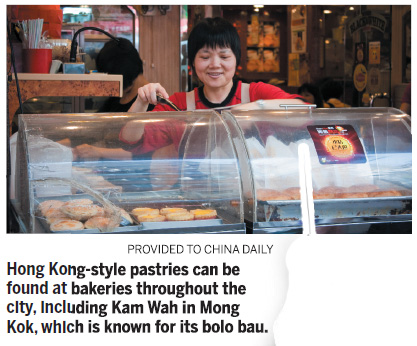

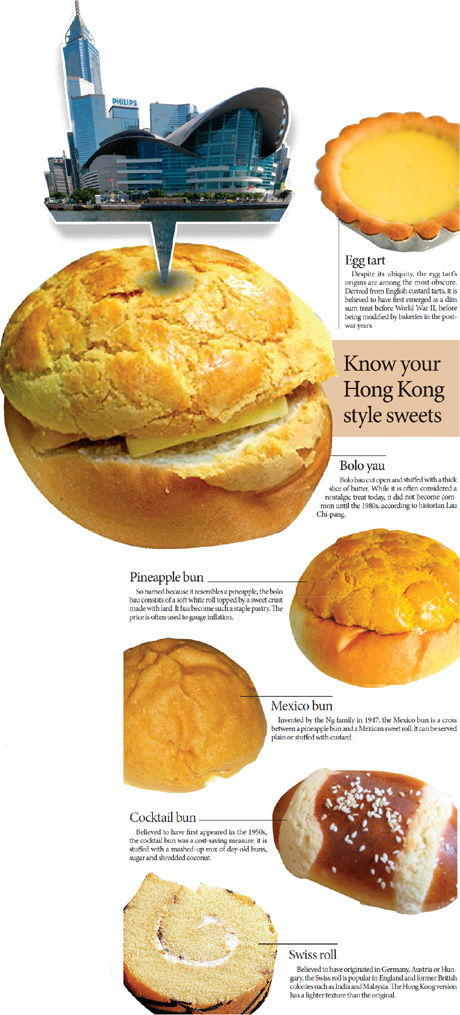

Every day for more than 60 years, the ovens of the Mido Caf have churned out dozens of crispy pineapple buns for breakfast tea. Better known by their Chinese name, bolo bau, pineapple buns are the most emblematic of Hong Kong snacks: light, fluffy and filling, with sweet, crunchy crust on top.

But when Mido's third-generation owner, 59-year-old Wong Sing-fan, is asked where the bolo bau comes from, she looks nonplussed. "It's from the British," she says hesitantly, before adding, "They have them in England, right?"

Hong Kong-style cuisine, known for its peculiar marriage of Western and Chinese tastes, is perhaps the city's most beloved contribution to the world, Cantopop aside. Local staples like bolo bau, milk tea and macaroni soup have followed Hong Kong people wherever they go, from the suburbs of Toronto to the streets of Shanghai. But for all their notoriety, the origins of these pastries, drinks and dishes are unclear.

"It's a bit of a mystery," says Lingnan University historian Lau Chi-pang while nibbling on an egg tart at Honolulu Caf in Wan Chai. "Some of us scholars are very interested in knowing where they came from, but it's quite tricky because their origins are not documented. Basically, we have no idea where to start."

A large part of the problem is that few bakers or cooks in the past bothered to write down their original recipes. That is especially true in the case of popular cuisine meant for everyday dining. With no food-obsessed TV shows or websites like OpenRice to document their creation, the story of how most dishes came to be has been lost to the fog of time.

"There's a lot of hearsay," says Lau. "I've been trying to figure out where pineapple buns come from for years with no luck. Some claim it's from Southeast Asia, but there's no evidence of it appearing in Singapore or Malaysia. One of my colleagues interviewed an old man in his nineties who claimed the bun was invented in Guangzhou. It's possible, since Guangzhou has a longer history of serving not-so-genuine Western pastries, but there are no bolo bau in Guangzhou today."

Two years ago, designer Oriana Reich and journalist Dora Chan embarked on a project to uncover the origins of Hong Kong pastries. They ran into the same problems as Lau: plenty of stories, and even some braggadocio, but little hard evidence.

"It's impossible to get anything too specific on any of these confections," says Chan. "Every bun and cake has a story that cannot be precisely traced."

Some stories are clearer than others, however. While the bolo bau remains a puzzle, its cousin the Mexico bun - which has a thin, sweet crust around the whole bun, rather than a thick crust on the top - was invented in 1947 by the Ng family, who had returned to Hong Kong after many years of living in Mexico. After opening the Mexico Bing Sutt, a caf on Shanghai Street, they created a signature bun that was a cross between a bolo bau and a traditional Mexican sweet roll.

Russians who fled to Hong Kong after the revolution in 1917 had an especially profound influence on the local cuisine. Unlike other Europeans, many of the local Russians were poor, and a number of them opened bakeries and restaurants. That was especially true in the late 1940s, during the Chinese Civil War, when a large number of Russians fled to Hong Kong from Harbin, Tianjin and Shanghai.

"It was actually the Russians who made the cha chaan teng (canteen) into a big thing where you have dinner sets with borscht, bread rolls and steak with soy sauce," says Chan. Some Russian restaurants and bakeries, such as Czarina on Bonham Road, Queen's Caf in Causeway Bay and Cherikoff in Mong Kok, continued to produce distinctive dishes long after their original owners immigrated to other countries.

Hong Kong-style cuisine didn't come into its own until the population boom of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, says Lau. "In prewar Hong Kong, Cafs and restaurants were very segregated. On the street, you had coffee stalls and dai pai dong (restaurant offering al fresco dining) selling toast, egg sandwiches and things like that. There were only a few high-quality Cafs serving genuinely Western food in Central and Tsim Sha Tsui, and genuinely Chinese restaurants like cha lau (teahouses)," he says.

With the growth of industry, tea stalls morphed into restaurants catering to the needs of a hungry population of factory workers. "By the late 60s and early 70s, local Cafs had started serving rice dishes and dinner, which was a major change," says Lau. "You had a good mix of all kinds of food - Chinese tea, English pastries, curry from Southeast Asia, instant noodles."

As time went by, dishes, drinks and pastries created from a blend of influences settled into a kind of standard. Today, one can walk into one of thousands of Hong Kong-style restaurants and be greeted by nearly identical menus based on standards like milk tea, baked spaghetti and white-bread sandwiches.

"You have restaurant owners that have been in the same business for three generations or more and they make the same things as everyone else because that's what people like," says Reich. "It becomes tradition just because it's been around for a long time."

That is especially true for pastries. "There are such obscure rules," says Chan. "Why is there always a red cherry on top of coconut tarts? Why must there be a lot of mayonnaise on tuna buns? It becomes almost codified. The inauthentic becomes authentic."

In their research, Chan and Reich found that, even if they had no clue about the origin of their dishes, bakery and restaurant owners had very specific ideas about how they should taste, look and feel. With the bolo bau, says Reich, "you have this distinct taste of margarine and pork fat, a real sweet-savory thing going on."

Milk tea, the most famous of Hong Kong beverages, is bound by the same tacit rules. "Hong Kong-style uses evaporated milk while Indian chai uses fresh milk that is cooked together with the tea, and (Malaysian) teh tarik uses condensed milk," says food writer Nana Chan.

To make a good cup of Hong Kong-style milk tea, she says, there needs to be a specific, hard-to-describe balance between temperature, fragrance, smoothness, color and thickness, all of which has to be "perfectly executed through carefully pulling the tea through thin cotton strainer that resembles a woman's stocking".

Howard Wong, general manager of the Association of Coffee and Tea of Hong Kong, estimates there are more than 3,000 Hong Kong-style restaurants in the city. His grandfather, Wong Kiu, owned a coffee and tea stall in the 1930s.

"Back then, a lot of these Cafs were for lower-income people," he says. "The docks were lined by these places." Because most of their customers worked labor-intensive jobs, they needed a strong pick-me-up, but one that wasn't too expensive - hence the use of evaporated milk, which is much cheaper than fresh milk and serves as a better counterweight to the strong flavor of the tea.

Over the past two years, Wong's association has organized an annual milk tea and coffee-making competition. Increasingly, many of the best competitors come from outside Hong Kong. In fact, the winner of last year's coffee competition was from Shenzhen.

Wong grew up in Toronto, where milk tea is a common drink in the many suburbs populated by Hong Kong people. "Now I spend more than half my time in Shanghai and I see a lot of Hong Kong-style restaurants opening up, and when you walk in, it's majority Shanghai people, not Hong Kong people," he says.

"That's something we can be proud of," says Lau Chi-pang. "In 1842, we started from nothing, and we imported all of our food culture. Now we are exporting it."

But will we ever be able to pinpoint the origins of Hong Kong's favorite dishes? As he finishes off his egg tart with a sip of milk tea, Lau deems it unlikely. "It provides a lot of room for imagination. I don't think we'll ever know for certain."

(HK Edition 04/28/2011 page4)