The great exodus

Updated: 2011-04-20 06:51

By Michelle Fei(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Over a 30-year period about a million people made their way into Hong Kong from the Chinese mainland. They risked their life and limb to find a better life and ended up providing the city with cheap labor pool and making it prosperous. Michelle Fei reports.

On a summer night in 1958, 16-year-old Tang Chi-yan ran away home. He and a fellow countryman were bound for the border separating the mainland and Hong Kong. Climbing over the border on Ng Tung Shan Mountain, linking the south end of Shenzhen with the Hong Kong border village of Sheung Shui, was one of the toughest things they'd ever done.

As far as Tang was concerned, it was his only hope to create a future. His father belonged to the hated "landlord class", and so Tang, having completed middle school, was banned from further education. Tang expected to be mired by his "special identity" in his hometown of Huiyang, Guangdong province, for the rest of his life.

"Let's go to Hong Kong!" One of Tang's friends suggested. Anyone who foreswore the socialist motherland and sought shelter in a capitalist colony was considered a "traitor" by the government of the day.

Once Tang and his friends were on there was no turning back. Tang and his friends hoped to sneak across the border to start a new life in Hong Kong. Failure meant imprisonment or death - being caught by the border police, falling off a cliff coming over the mountains.

"My heart was quaking when I heard the barking of police dogs approaching," said Tang.

"I saw the iron net (border gate) right in front of me and one of my friends shouted 'jump!', and then I jumped," Tang added, recalling how he and his companies made it through the border safely that night.

Tang did not realize that he was among the pioneers of what was to become a large historic group of escapees.

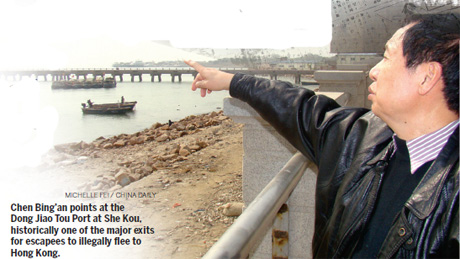

During the 1950s to 1980s, it was estimated that approximately one million mainland residents escaped to Hong Kong via the Shenzhen border. The exodus was believed the largest one ever recorded during the Cold War period, in terms of both numbers and duration, according to Chen Bing'an, a mainland journalist who completed a book on the escapees in October 2010, titled The Grand Exodus, or Da Tao Gang in pinyin.

"People know only that the city (Shenzhen) developed after the famous opening-up policy. However, there are few people who know that it was the tears and blood of the escapees that inspired the introduction of the opening-up policy," said Chen.

"By revealing the history of the exodus, I want to remind people, especially the young ones, where the city's roots lie," noted Chen.

Last year also marked the 30th anniversary of Shenzhen's becoming China's first economic reform zone. Chen's book was considered something of a "precious gift" to the city.

Chen said he believed that the history of the exodus was equally important for Hong Kong as for these illegal immigrant who provided cheap labor to fuel Hong Kong's rapid economic development, and who made grand contribution to the city's "economic miracle" that happened during the 1960s and 1970s.

"Forget the economic indices, policies, the prosperity of Hong Kong was built by tears and blood of mainland refugees!" said Ye Xiaoming, who fled to Hong Kong in the 1970s and was interviewed by Chen.

Till the end of the 20th century, it was said that among the 100 richest people of Hong Kong, more than 40 of them fled to Hong Kong during the 1960s and 1970s. These included the founder of Goldlion Holdings Ltd Tsang Hin-chi, founder of Giordano International Limited and Next Media Limited Lai Chee-ying, and "Futures Godfather" Liu Mengxiong, who is now a Hong Kong member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference National Committee.

The history of the exodus remained unknown among most Chinese people for about half-century.

Documentaries concerning the exodus were considered "sensitive" and "forbidden" till the central government decided to change its policy in 2007. Chen's book was the first one to reveal stories of people once involved in the grand exodus.

It took him 22 years to explore the history as few people were prepared to recount their former sadness and pain. Many lost their families during the risky journey, some right before their eyes.

The Shenzhen River serves as the natural border between Hong Kong and Chinese mainland. The narrowest part of river is only two-meters wide. One can across it in a single bound. One of the major routes for the exodus was to climb over the eastern border on Ng Tung Shan Mountain, where the Shenzhen River starts, and sneak into Hong Kong via the Sha Tau Kok area.

Many others stowed away or swam across the Shenzhen River via western She Kou or Shenzhen Bay area, reaching Hong Kong's Yuen Long District.

Tens of thousands of mainland refugees flocked to the border to seek a better life in the colony. However, many of them were not as lucky as Tang.

Many were swallowed up in the ocean; some were shot dead by mainland border police; others were just too weak to make to the end, according to Chen.

"I didn't realize how lucky I was until I heard from my younger brother later that he was caught near the border twice and was bitten by police dogs," said Tang, adding that many of his fellow townsmen tried to copy their experience but failed to make that far.

"I still remember that many dead bodies of mainland refugees could be seen on the seashore of northern Hong Kong everyday during those days. Some were found with dog bites, some even had bullet holes," said Tang's wife, Chow Kee-lin, a local-born Hong Kong resident.

An industry of "body draggers" once flourished during the area in Shenzhen. Workers would drift in the river, retrieve bodies and bury them. The draggers were paid by the government. There were so many corpses that many of the draggers prospered, according to Chen.

Besides "body draggers", there was the illegal trade of "drifter host" that boomed across the border. Escapees were "hosted" - pretty much the same as being kidnapped-- at shattered metal sheds located under Ng Tong Shan Mountain, waiting for their Hong Kong relatives or acquaintances to pick them up, after a sum of money was paid to the "host", according to Tang.

"I was later kicked out of the shelter when they found out that no one's going to pick me up," said Tang.

Having no contact with his relatives in the city, Tang could do nothing but to drift onto the street.

"Most Hong Kong people were willing to help these refugees, giving them toast, bread and sugar," recalled Tang's wife.

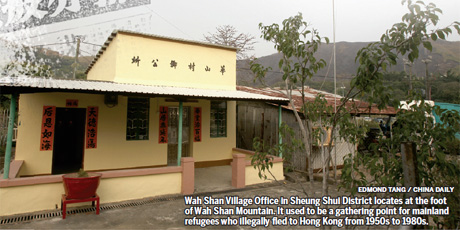

"We not only helped strangers we came across on the street, but also went to Wah Shan to pick them up as many of them were actually our relatives," said Tang's wife.

Wah Shan Mountain, at the border town of Sheung Shui, was a gathering point for mainland refugees at that time. They had a lot of sympathy among Hong Kong people.

The headline for Sing Tao Daily published on May 17, 1962 read "historic high numbers of refugees recorded at the border".

The article stated that over 3,000 mainland refugees were reported being arrested at the border in one day, with the total number of refugees arrested in first half of May reaching 25,000.

In the face of those high numbers, over 2,000 Hong Kong residents were reported rushing to the mountain with food and water to help the refugees.

When hundreds of police cars carrying nearly 30,000 refugees moved slowly towards the border to return them to the mainland, an astonishing thing happened.

Thousands of Hong Kong residents surrounded the police cars. They stood waving goodbye to family members in the police cars. Then, one Hong Kong resident lay down on the road to stop the cars and shouted "run!" Many other residents joined him. Thousands of refugees then jumped off the vehicles and ran, assisted by local residents' help, according to Hong Kong media reports.

"They were forced to flee to Hong Kong by hunger and poverty, even at the price of their lives," said Chen.

He reckoned that poverty was the most direct cause of the grand exodus. However, "inappropriate policies" was the true reason behind them, said Chen.

On Chen's notebook, a red curve on a chart marked the numbers of escapees during the 30 years from the mainland. The first exodus can be traced back to 1955. The escapees flowed to the boundary at Shenzhen from 12 provinces, including Guangdong, Hunan, and Hubei.

Four peaks were recorded in 1957, 1962, 1972 and 1979, involving some 560,000 people, according to Chen's research.

"The curve of the exodus intrinsically was linked with political moves. The chart was a clear reflection of the nation's policy and economic development," said Chen.

Chen cited three major political moves during the 1950s through to the 1980s: the Great Leap Forward (1958); the Three Years of Famine (1959-1961), which Chen believed to be a consequence of the Great Leap Forward campaign but was officially declared to be a natural disaster; then the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

"These political moves gave the young regime a hard time, impoverished the country, and more importantly, left millions of people of the grassroots with their lives hanging in the air," said Chen.

"The majority of the exodus was farmer. They didn't know much about politics or democracy; they only cared about where they could find food, where they could keep their heads above ground," said Chen.

"Socialism or capitalism? People voted with their feet, not their hands," said Chen.

Today, a half-century after the grand exodus, villagers at Hong Kong's Wah Shan village are still reluctant to recall the history.

"Why you ask about the history? What do you want?" a villager who had lived in Wah Shan for over 40 years questioned first instead of giving direct answers. In his 80s, the villager remains fully alert about the topic.

"There used to be lots of mainland people lingering on the mountain. They climbed over the border and waited for their relatives," recalled the elderly villager.

"I had a friend that came to Hong Kong in this way," he said.

The villager, born on the mainland and came to Hong Kong in the 1970s, claimed himself as a legal immigrant, not like these refugees.

Since publication of the book, Chen said he has received emails from several compatriots who once joined the exodus to Hong Kong and now have moved aboard. They are considering setting up a group to record their common history.

|

The book, named The Grand Exodus, or Da Tao Gang in pinyin, took mainland journalist Chen Bing'an 22 years to write and was published on the mainland in October 2010. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

(HK Edition 04/20/2011 page4)