Keeping kosher

Updated: 2010-12-08 07:04

By Christopher DeWolf(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

Asher Oser, Ohel Leah's new rabbi, describes Hong Kong's Jewish community as "a transient place, yet there are deep roots." Provided to China Daily |

Barely visible among Hong Kong's cosmopolitan population lives a small community of about 5,000 Jews. The Jewish community, that dates back to the beginning of the colonial era, has played a significant part in the history of the city. Christopher DeWolf reports.

Rabbi Asher Oser opens the heavy doors to Ohel Leah and steps inside, pausing for a moment to consider its vaulted ceiling, intricate woodwork and marble floors. As the door closes behind him, the sound of traffic fades, replaced by the quietude of Hong Kong's oldest synagogue.

"It's a building of such history and gravitas, but if you walk in here on a Saturday morning, there are kids running around and it's full of life," he says. "It's the kind of contradiction that I love. And I think what Judaism does is it tries to make sense of those contradictions."

Less than two months ago, Oser arrived in Hong Kong to lead Ohel Leah, a Jewish Modern Orthodox congregation that is nearly as old as Hong Kong itself. He is still finding his feet. Walking towards the Torah ark, where the synagogue's sacred scrolls are kept, he finds it padlocked. "I don't actually have the key," he says with a chuckle.

But Oser, who was born in Australia, educated in Canada and most recently served as the rabbi for a congregation in Providence, Rhode Island, is already enraptured by his new community in Hong Kong. "There are few Jews here, and it's a transient place, yet there are deep roots," he says.

The first Jews arrived in Hong Kong with the British in 1842. Some were European traders who had previously been based in Canton, now known as Guangzhou, but most were employees or relatives of Iraqi Jewish families that had followed the British Empire through Asia, from Bombay to Rangoon, Penang, Singapore and finally Hong Kong and Shanghai. The community was formally recognized in 1858, when the colonial British government granted Jewish families land for a cemetery in Happy Valley.

Since then, Hong Kong's Jewish population has grown from a few hundred to more than 5,000, though the precise number is elusive, since so many of Hong Kong's Jews are expatriates from the United States, France, Israel and other countries. Though it remains small by Western standards, the community is remarkably active and diverse, with five congregations, a lively community center, a school, a newspaper, a magazine and even a film festival.

"We don't have the amenities that we would have in Toronto or New York but we're very lucky with what we do have," says Howard Elias, the founder of the Hong Kong Jewish Film Festival, which recently wrapped up its 11th edition.

On the surface, Hong Kong is not the most accommodating place for an observant Jew, who is required to observe kashrut, a series of dietary laws that prohibits the consumption of pork, shellfish and other food that has not been judged kosher by a rabbi. But when he first came here nearly two decades ago, Elias was surprised by the diversity of Jewish life. "People are from everywhere, even from countries where I didn't know there were Jews, like Zaire," he says.

A century ago, Jewish Hong Kong was a far more insular place. It was dominated by three Iraqi Jewish families, the Sassoons, Kadoories and Hardoons, who also maintained a presence in Shanghai, which had an even larger and more active Jewish community than Hong Kong. Import and export was where the families made their money: in the late 19th century, the Sassoons controlled as much as 70 percent of China's opium trade.

Ohel Leah was built in 1901 with money from the Sassoon family. Its Middle Eastern influence could be felt in the architecture and prayer services, which followed the Sephardic traditions of Jews that found refuge in countries like Iraq after being expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492. Arabic was the community's lingua franca; in 1925, when the congregation needed a cantor to lead song and prayer, it hired one from Baghdad.

But there were also Ashkenazi Jews from Europe, including Sir Matthew Nathan, who governed Hong Kong from 1904 to 1907. Though he was considered the symbolic head of the community, he kept a distance, partly because its Sephardic traditions were foreign to him, and partly because of colonial politics. Though it was secular in practice, the British Empire was officially Anglican, and as governor of Hong Kong, Nathan was the titular head of St. John's Cathedral - an odd position for a Jew.

"It was obviously a conflict," says Judy Green, the chairwoman of the Jewish Historical Society of Hong Kong. "He tread a very fine line. He was aware of his Jewishness but he wasn't able to be very active."

Politics caught up to Hong Kong's other European Jews, too. In the early 20th century, there were 30 to 40 families who had arrived after fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe. "They were inn-keepers and cafe owners and considered low-lifes by the Sephardim," says Green. Among those families were the Greens, who came to Hong Kong in the 1900s from Romania. (They were originally Yiddish-speakers, but their name was anglicized at some point after their arrival.) At the time, Romania was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Greens were branded enemy aliens during World War I and forced to leave for Shanghai.

The tides turned after World War II. While most of Hong Kong's Jews were interned by the Japanese, Shanghai had become a haven for those fleeing from the Holocaust. When the Chinese Civil War resumed in 1946, Shanghai's Jews began leaving for Hong Kong. Though most eventually moved overseas, the families that stayed - including the Greens - put down roots.

"It was an infusion of new blood," says Green. "It just totally revived the community." The Jewish Club, which was located next to Ohel Leah and had been destroyed during the war, was rebuilt. Community life flourished. But it was, in many ways, an almost secular community. "There would be stretches, a year or so, without a rabbi," recalled Green's husband, Michael, at a talk given to the Historical Society last year. Instead of being kosher, the restaurant inside the Jewish Club was "kosher-style."

Things began to change in the 1980s, with Hong Kong's emergence as an international business hub. An influx of Jewish expatriates created what Judy Green describes as "a critical mass of people who wanted to pray." New congregations were founded, representing the spectrum of international Judaism, from the liberal United Jewish Congregation to the ultra-orthodox Chabad Lubavitch movement.

In 1995, Ohel Leah sold the development rights to its gardens to a property developer, which funded the restoration of the synagogue and the construction of a large new Jewish Community Centre, which includes a library, supermarket, swimming pool and a strictly kosher restaurant.

The sudden expansion of the community wasn't without conflict. "The old saying goes, 'Two Jews, three opinions,'" says Rabbi Oser. When the new community center opened, an Israeli Orthodox rabbi complained that it was too secular. And the old Sephardic-Ashkenazi division lingers on, to some extent. With the recent influx of Europeans and North Americans, Ohel Leah has now become an essentially Ashkenazi synagogue, though it combines elements of both traditions. In 1995, a group of Syrian-American businessmen founded a new Sephardic synagogue, Kehilat Zion, in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Still, the squabbles remain minor, and in some cases amusing. Erica Lyons, a lawyer from New York who moved to Hong Kong eight years ago, enrolled her children at the local Jewish primary school and found that parents were split in their opinion on what the school canteen should serve for lunch. "The American parents wanted their kids to have something small, like a sandwich, but the French and Israeli parents were used to their children being served these big hot lunches," she says. The solution? Both options are now available to students.

Lyons hopes to capture the community's diversity in a new quarterly magazine, Asian Jewish Life, that launched earlier this year. "It really is a melting pot of all different cultures and nationalities, and here, you're interconnected with all the other pockets of Jewish life in the Far East," she says.

Though there are several congregations, the singular presence of the Jewish Community Centre prevents people from "segregating themselves" the way they would in cities with large Jewish populations, says Lyons. "You're in a big city but you have a small town kind of life, which really pulls you into the Jewish community and makes you a bit more involved than would be back home."

The community's small size and diverse nature has led to some peculiar arrangements. Ohel Leah and the Jewish Community Centre are maintained by an Orthodox trust, which also sponsors the United Jewish Congregation - the only example in the world of a Reform congregation being funded by an Orthodox one.

Hong Kong's Jews have also had an outsized impact on the city as a whole. The Kadoorie family, which owns China Light and Power as well as a variety of other businesses, has been involved in charitable activities for decades. In the 1950s, the Kadoorie Agricultural Aid Association helped poverty-stricken refugees from the Chinese mainland start farming in the New Territories by giving them pigs, interest-free loans and agricultural training. (The family's patriarch, Lord Lawrence Kadoorie, once quipped that he knew everything about pigs but the taste.) More recently, Sir Michael Kadoorie discovered a treasure trove of historical archives in his family's offices, which he has used to launch the Hong Kong Heritage Project, a non-profit initiative to raise awareness about Hong Kong's history.

History is another thing that binds the community together, especially when so many of its members are newcomers or expats who might not stay in Hong Kong for more than a few years. When the Jewish Historical Society was first founded in the 1980s, one of its first acts was to catalogue all of the gravestones in the Jewish Cemetery. "It's a very higgledy-piggledy cemetery, but it's gorgeous," says Judy Green. "It's right behind a Buddhist monastery and you can hear the nuns chanting. It's very peaceful."

That kind of incongruity is what Rabbi Oser finds so exciting about his new position in Hong Kong. "Everyone is trying to deal with the challenges of being a 21st century Jew in Asia," he says. "God doesn't say live here, live there. People thought that Jewish life would never flourish in the United States, but Jewish life is able to adapt to many different contexts. You can walk into a congregation and they're reading the same texts, but there's a different flavor - a French flavor, an American flavor, an Israeli flavor. I think there will be an eventual Asianization of Judaism."

Standing outside Ohel Leah, next to a poster advertising a Hanukkah junk trip for teens, he looks up at the synagogue's beige facade. "You stand here and it's a place of history," he says. "You're not just one person standing here. That's how people come to have a Jewish identity. You're part of a Jewish past."

|

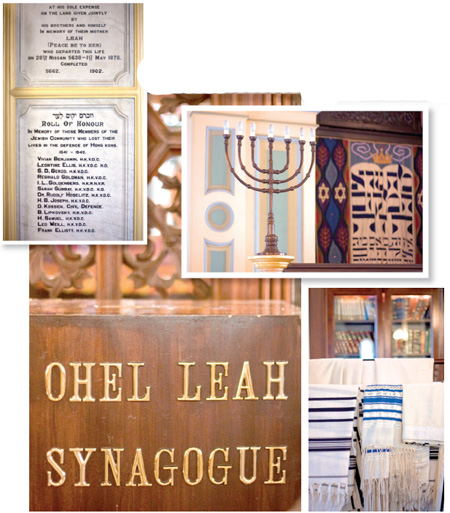

Ohel Leah, which opened in 1902, is one of the oldest synagogues in Asia. It is now home to a Modern Orthodox congregation whose members hail from around the world. Photos Provided to China Daily |

(HK Edition 12/08/2010 page4)