Mushroom as pollution mask

Updated: 2010-09-10 07:06

By Emma Dai(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

Researchers at Chinese University of Hong Kong install "mushroom barrier" along the street as a superb, natural defense against air pollution. Provided to China Daily |

|

Amy Lam manages a mushroom farm in New Territories. The farm produces pleurotus, a popular fungus, which is used in Chinese University of Hong Kong's experiments. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

A team of Hong Kong researchers has discovered that mushroom serves as a hugely effective ally in the fight against air pollution. Now, a reserach team awaits the go-ahead for a full-scale testing. Emma Dai reports.

For many, the mushroom is a gourmet food, a sensual delight, full of unexpected flavors. Researchers at Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) consider the "mushroom barrier" a superb, natural defense for the future, against air pollution.

The team built its mushroom barrier along a major highway in the New Territories.

"We are the first in the world to look into mushrooms' potential in treating air pollution," said Chiu Siu-wai, the professor who is leading the research. "Very efficient it is." In a month of field testing on mushrooms, the team recorded significant reductions in concentrations of organic air pollutants.

Concentrations of nitrogen dioxide were reduced by up to 50 percent within 10 minutes. The average reduction was an impressive 10 percent. Noise pollution was reduced by three decibels.

At another site, outside St Paul's Hospital at Causeway Bay, one of the most polluted areas in the city, concentrations of nitrogen dioxide were reduced by 50 percent at best and 19 percent on average. The barriers also had a cooling effect, reducing adjacent temperature from 40 degrees to 35 degrees.

The mushroom barriers are not aesthetically pleasing. They're really rather shabby - formed of spent mushroom substrates made of chopped straw, paper and wood stuffed in plastic baskets.

The caps and stems of the fungi had been previously harvested but their hyphae, or "roots", continue to thrive and grow inside the substrates. As they are growing they produce enzymes that can degrade organic pollutants such as hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides. They also absorb airborne heavy metals. Hyphae eat pollutants and grow. No extra fertilizer is needed. That makes spent mushroom substrates just the right thing to purify vehicle exhaust.

"I've been working on mushrooms for more than 10 years," said Chiu. "Previous discoveries using them to curb soil and water pollution inspired me." After testing several kinds of mushrooms, the team concluded the enzyme produced by pleurotus, a popular fungus, was the most efficient air cleaner.

Lab experiments saw even more astonishing results. The mushroom's efficiency in degrading pollutants in mid-polluted environment can reach the 90 percent level.

During the course of the field work, the city experienced almost all the extremes of weather imaginable during a tropical summer. Amid the downpour of black rainstorms, Chiu and her students had to brave the elements to collect their data. "We were wet from top to toe." Chiu said. "But we are happy to see that our barriers survived."

The pollution sometimes overwhelmed the barriers, occupying their tiny site. "We only have two layers of substrates," Chiu said. "Once overloaded, their efficiency would drop. I believe the result could be better if there were enough (substrates) to absorb more pollutants."

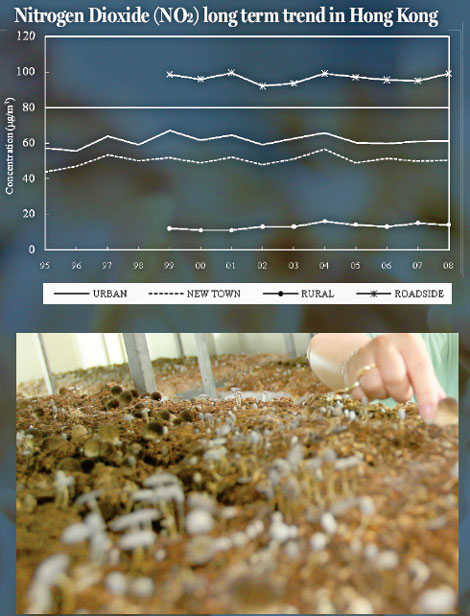

Despite government efforts, air pollution in Hong Kong has been at alarming levels for decades. From time to time, the city chokes in smog, downtown particularly. Vehicle exhaust is one of the most significant contributors. While 4 percent land of the city is occupied by residences, traffic arteries account for 3 percent. The air along the roadways is much more poisonous than the average urban atmospheric environment. The gap between roadsides and rural area is even greater. (See chart)

Last month the Environmental Protection Department recorded roadside conditions as "highly" polluted, in three quarters of the tests carried out. About 8 percent of test results during the month produced "very high" pollution readings, indicating that people with heart or respiratory illnesses should "avoid prolonged stays" in heavy traffic areas.

"I used to think there would be a lot of complaints about our field settings. The barriers were crude," Chiu said with a broad smile. "I told my students to collect as much data as they could in the first week in case any withdraw order came." But later the team found understanding and support from the neighborhood. When the team collected samples in Causeway Bay, students, retired people and ordinary working people came to ask what was going on. People who came were open-minded and full of curiosity.

The local authorities however were not enthusiastic about the research. The team applied to the authorities to carry out field testing on a large scale, and received no reply. Thus, there is no funding for large-scale testing. "I don't know to whom they gave the money," Chiu shrugged. "Luckily I have some savings and this is not expensive to do."

The experiments got the go-ahead, when a "friendly construction company" allowed the researchers to put their substrate barriers inside their road sites. The researchers were required to undertake three training sessions on safety. The testing materials were waste material from the university's mushroom farm, so the cost for the field work was really low. Much of the cost was for chemical analysis.

"This is a promising field," Chiu said enthusiastically. "It could have a wide application: as a median strip on high way; at bus stops, parks; even to purify air inside cars. Besides, it also exploits waste from mushroom production and needs only a little water to sustain."

Even in Hong Kong, the tiny city arguably having no place for agriculture, five mushroom farms exist, providing 32.5 tons of mushrooms a year (2009).

At the New Territories farm of Peninsular Innovations, a leading mushroom producer, nearly one ton of pleurotus is harvested every year. "A substrate pack can raise two batches of pleurotus. Each takes seven to eight days to mature," said general manager, Amy Lam, as she walked through the greenhouse. "We discard more than 500 old packs once every two weeks, creating seven tons of substrates a year." Once a headache bound for the landfill, the wastes are now dried and given to organic farms as soil conditioners and fertilizer. "Basically for free," Lam said. "Orchid farmers sometimes pay as they wish."

Chiu has not tried to patent the innovation in pollution control. "I would be far richer if I opened my own business," she laughed. "Commerce is not my cup of tea. My interest is finding more innovations."

"This is not only for Hong Kong," she added. "I hope whoever thinks it worthy feels free to dig. I hope those interested will go ahead and make modification. Only in this way can the field be well-shaped and the invention further developed. I'd be happy to answer questions."

In her view, lab experiments and practice should go hand in hand. "I am in favor of a broad study and test of the substrates and discover their limits for reducing air pollution. We would put substrate barriers along a high way, just like sound barriers," Chiu said. "That wouldn't bother the traffic, but will help reduce noise pollution," she added.

Such an exercise, which is beyond the means of the research team, requires the government's support. "We cannot do much unless we have more resources," Chiu said. "But of course, it's also my responsibility to my students."

(HK Edition 09/10/2010 page4)