Insurance-induced suicide: grim facts, tragic tales of hopelessness

Updated: 2010-07-08 07:36

By Simon Parry(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

|

A few atypical suicide cases have raised questions over whether the way life insurance is sold may add to the suicide death toll. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

Financial or emotional stress drives a young husband to cash in his life for a big insurance payout. Through a bizarre twist of business logic, Hong Kong insurance companies may unwittingly be causing as well as assisting such 'death by insurance' suicides. Simon Parry reports.

Anguished and alone in his home in the minutes before he took his own life, the family man who would soon become just another of Hong Kong's suicide statistics showed surprising clarity of mind as he sat down and spelled out his final thoughts.

In a letter to his wife and two young children, he explained as best he could why he had decided to end his life. Then, beside the letter, he placed the paperwork for five separate life insurance policies he had taken out, leaving them with a total payout approaching HK$4 million.

Two of the five policies had been taken out just over one year before he died - making his family eligible for the full payout and just bypassing a 12-month exclusion period for payouts on suicide cases in Hong Kong life insurance policies.

This suicide, it seemed, hadn't just been planned to the last hour: It has also been planned to the last dollar in terms of how much it would be worth to the family he left behind.

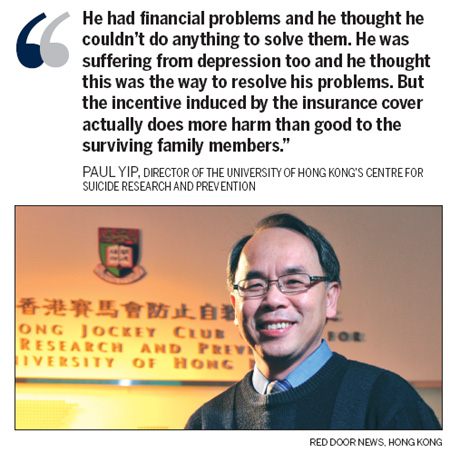

"They got the money - they met all the requirements so the insurance companies had to pay out," said Paul Yip, director of the University of Hong Kong's Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention.

But if the man thought he was being a good husband and father by doing what he did - taking out insurance policies in an apparently calculated way and planning his death for more than 12 months - he couldn't have been more wrong, according to Yip.

"We asked his family about it afterwards and they told us very clearly 'We don't want the money. We want him back'," he said. "They valued him as a husband and a father and the money meant nothing to them.

"He had financial problems and he thought he couldn't do anything to solve them. He was suffering from depression too and he thought this was the way to resolve his problems. But the incentive induced by the insurance cover actually does more harm than good to the surviving family members," Yip observed.

The man's death four years ago and an unknown number since raise the question of whether he would have committed suicide if he had not believed he was worth more dead than alive. It also raises questions over whether the way life insurance is sold may add to the suicide death toll.

Yip and his colleagues believe lives could be saved if the exclusion period for life insurance payouts on suicide cases is extended from one to three years - and they have produced a detailed academic study to back their argument.

The study, to be published in the international journal Crisis, examines the link between suicides and life insurance payouts over a seven-year period in Australia, where the suicide exclusion period is 13 months.

It detected a sharp rise in life insurance claims from 13 months after the policies were taken out and a corresponding drop three to four years into the policy. Extending the suicide pay-out exclusion period to three years could, therefore, prevent at least some "insurance-induced suicides", the academics say.

Written in conjunction with experts from the University of Melbourne and the Singapore Clinical Research Institute, the paper argues that there is a moral responsibility on life insurance agents to act as "gatekeepers" when dealing with potentially suicidal clients.

It also argues that extending the exclusion period would be a win-win scenario for society and insurance companies. "Suicide deaths not only cause a loss of productivity in the community, but also certainly increase insurance premiums," the paper says.

"If suicide deaths could be removed or reduced, the life expectancy for the whole population would be longer and life insurance premiums would surely fall. More importantly, the waste of human lives and the emotional pain caused to the survivors are a primary concern. Of course, insurance companies would be able to save money too."

It may seem a compelling argument, but the reality is that long before this current study was completed, insurance companies resisted any moves to extend the payout exclusion period for suicide cases. In Hong Kong and many other countries, the exclusion period is 12 months and only the US currently has a longer exclusion period of two years.

Asked why he thought this was, Yip, who has for years lobbied the Hong Kong Federation of Insurers for a policy change, said, "Insurance companies are very sensitive to this proposal because life insurance is a big market.

"Only around half of all people have life insurance, so insurance companies want the policies to have a good image so they can go out and get a bigger share of the market. They don't want to have any negative publicity over life insurance.

"If you come out and tell people there are some individuals who buy life insurance so their families can collect the payout if they die from suicide, it will have a negative effect on customers.

"Insurance companies have already built that consideration into the calculation of the premiums so that there is a proportion to pay for the suicides. It is a business consideration."

Yip said he did not believe that the people who committed suicide shortly after suicide exclusion periods of life insurance policies necessarily took out the policies with the intention of killing themselves.

What may happen in many cases, he said, is that the person takes out the policy and, weeks or months later, goes through a difficult time or loses his job. The thought of the insurance payout then occurs to him and he begins to formulate a suicide plan.

Tragically, although their numbers are relatively small, the deaths of the people involved in induced suicides of this kind are often devastating to those left behind. They are often breadwinners and parents to small children as well as the supporters of elderly parents. "Their loss can have a devastating effect on society," Yip said.

Yip believes there is a moral obligation on insurance agents to seek intervention if they believe someone is taking out a policy with a view to committing suicide and getting a payout for their family once the exclusion period is over.

However, the way policies have been sold has encouraged them to overlook that obligation, he said. "The bonus for insurance agents is sometimes calculated on the first annual premium. After the first year, the money goes to the company, not the agent," he said. "So the agent's concern is just to sell as many policies as possible ... They are under a lot of pressure."

Peter Tam, executive director of the Hong Kong Federation of Insurers, who has been sent a copy of the academic paper, declined to answer a question from China Daily on whether he supported the proposal to raise the suicide exclusion period on life insurance policies to three years.

However, he dismissed Yip's suggestions that insurers were more concerned about selling policies than saving lives or that they were overlooking their moral obligation in any way as "unfair to our industry".

"The remarks are grossly unfair, but we'll nevertheless contact Yip to understand more about his arguments and recommendations," Tam said in a written response.

As an indication that he supports keeping the current exclusion period of 12 months, he said, "Life insurance is taken by people to protect their families and loved ones and we can never lose sight of this." However, he added, "As a caring industry, we will continue to support any practical initiatives aimed at reducing suicides.

"We will, for example, continue to work with the Hong Kong Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention in developing information material for agents so that they're better equipped to understand what depression is and encourage clients with signs of depression to seek early professional help."

Yip confirmed that he and his colleagues had already, some years earlier, spoken to insurance agents at the invitation of the Hong Kong Federation of Insurers with advice on how to act as "gatekeepers". The session was not a great success and has not so far been repeated, Yip admitted.

"The agents told us they were worried they would not sell as many contracts if they followed our suggestions and might lose their jobs or make less money," he said. "They actually joked to us 'We might end up committing suicide ourselves.'"

It is a joke that will have a hollow ring for the relatives left behind in suicide cases linked to insurance payouts. Yip recalled another more recent case in which a young father appears to have had an insurance payout as at least one of the factors in his decision to take his own life.

"I personally went to the mortuary to see this young man aged about 35 who jumped off a building and I saw his wife who had gone there to identify his body. They had a 5-year-old daughter," he said.

"The husband had taken out life insurance worth a lot of money but she kept crying and told me she just wanted him alive so they could face their difficulties together. She said she would pay the insurance money back 10 times over if she could only get her husband back."

(HK Edition 07/08/2010 page2)