Setting their sights on the movies

Updated: 2010-06-30 07:39

By Sherry Lee(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

|

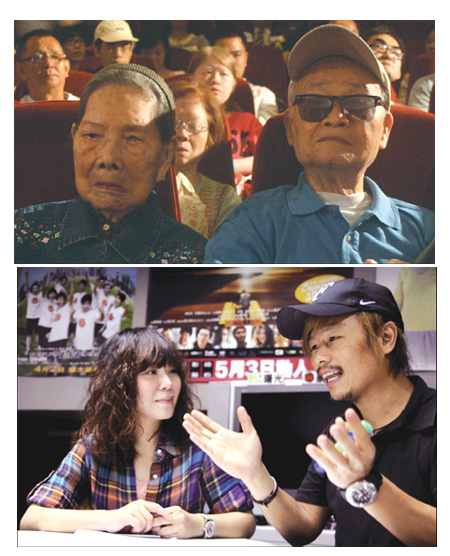

Top: Blind and visually impaired people watch a film accompanied by verbal descriptions. Above: Adrian Kwan Shun-fai (right) and Hannah Chang Pui-king promote barrier-free movies for the blind. Below: Radio and TV host Pang Ching narrates a film for blind and visually impaired viewers. Provided To China Daily |

Hong Kong lags behind many other cities in providing access for people with visual impairment. One local group has banded together with the aim of providing descriptive audio tracks so that blind people are able to enjoy films along with everyone else. Sherry Lee reports.

Tsui Yu-hang loves to go to the movies. He never goes alone. He has to have somebody with him who can describe the on-screen action.

Tsui, 22, is visually impaired as a result of a congenital retinal disorder.

Tsui gets as much as he can from listening to film dialogue, sitting in the front row - trying to distinguish what's on the screen with only 10 percent vision.

"I can only see light to feel the mood to try to understand the movie. I can't see the action," Tsui says.

"Each time after watching a film, my eyes are so tired."

His pain mirrors the lives of Hong Kong's 120,000 blind and visually impaired.

Movie scenes that have no dialogue are lost on them. They don't see the eye contact between the characters, the facial expressions, the landscapes. People who are visually impaired can't grasp what's unfolding in a film. Many simply don't go and haven't been to a screening for years.

That may change with the help of a few dedicated people. Emily Chan manages an organization for blind people. She's gotten together with Adrian Kwan Shun-fai and Creation TV script writer Hannah Chang Pui-king to try to solve the problem.

On June 11, they hosted the first screening for the blind accompanied by verbal descriptions at a Kowloon Tong cinema. Over 100 visually impaired people turned out. The hope of the organizers is that film producers and cinemas will join in the project and have more screenings for the blind.

"We should help blind people to watch movies. They are also human beings," says Kwan, 41.

With pressure from the government and human rights groups, films with audio description for the visual and hearing impaired, known as "barrier free movies", became available at cinemas in the United States and Canada by the early 1990s.

In Germany and Austria, there are websites to introduce barrier free movies and trailers. There are workshops for writers of audio description, and even DVD menus are barrier free.

In May, Paris hosted, for the first time a film festival for the visually impaired with audio descriptions to help audience members follow plots.

Visually impaired, Clayton Lo Keng-chi is researching audio guidance for the blind. He is critical of Hong Kong's cultural policy saying it marginalizes the visually impaired from the main stream.

A spokeswoman for the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) says the department cannot provide audio description service for all performing arts programs "due to substantial resources implications and technical considerations".

A student of film and literature at the University of Hong Kong, Lo says films can broaden the perspective of blind people, and raise their knowledge base.

Providing barrier free movies can increase rights of the visually impaired in Hong Kong where the focus is still on guided paths, he says.

Tsui believes his inability to watch films makes it difficult for him to integrate into society.

"My university friends often talk about movies, but I can't catch what they are talking about," says Tsui, who studies economics at the Chinese University.

Even when he goes to a movie he often misses key parts of the story. He says his friends have to enjoy the film for themselves and cannot fully describe the plots to him.

"One day my classmates talked about how one character was beaten to death in (the film) Ip Man. I watched the film but didn't even know that the person was killed. I felt so embarrassed."

Lo lost 70 percent of his sight at the age of 15. He often has to pause visual images to gaze at them on his computer screen to catch the expressions of the characters and the film's action.

"I can't enjoy the movie," he says sadly.

Emily Chan was born with only 10 percent sight. When she watches a film she sees the images as a blur. As a result, she wasn't interested in movies.

She learned about movies for the blind in the United States in 1994.

"I saw that a theatre provided headphones with a soundtrack for blind people to watch a drama," Chan says, adding that video tapes with soundtracks for the blind were also sold in shops.

She didn't plan to take the idea to Hong Kong.

But after a few occasions hearing friends talk about movies, she felt she was missing something.

"I felt left out," recalls Chan. "I started thinking of helping the blind watch movies."

In 2008, Chan joined the Hong Kong Society for the Blind as the manager of its Shek Kip Mei center with a responsibility to initiate new projects.

Chan started to put her idea about films for the blind into practice.

She met RTHK radio host Jacqueline Pang Ching and invited her to act as narrator for films.

After the first trial, Pang gathered heaps of video tapes and watched them to find the best narration technique.

In March 2009, the two started their biweekly showing at the center.

Many movies attract a full house of 60 to 70 visually impaired people.

Pang trained over 20 volunteers. Former TV actress Annie Liu On-lai, radio host Herman Cheng Ho-man and newspaper columnist Wong Ming-lok joined their ranks.

In January, a director of a new program, Dreams Come True, on Creation TV, passed by Chan's center and learned about movie narration services for the blind.

He mentioned this to Adrian Kwan, Dreams' production consultant.

Kwan proposed to Chan that he narrate his film, Team of Miracle: We will Rock You, with the process of his narration recorded to be broadcast as one episode of Dreams Come True.

Team of Miracle features how a group of street sleepers learnt to play soccer to regain their self- confidence.

Pang trained him and Kwan did his first narration in March.

"I have to use concise language. I learned to forget what I didn't say about a happening and just focus on what is coming," he says.

Attending a film school in Canada, Kwan began his career in movies in 1994 as an assistant director on numerous Hong Kong films, before becoming a filmmaker in 1999. He worked with Peter Chan Ho Sun in many of his earlier box-office hits.

Kwan moved on to make Christian films in recent years, making many inspiring movies such as Miracle Box.

"I like to use my films to inspire people," Kwan says.

His narration for the blind inspired him to help them.

"At the screening, one man said he wished so much to go to a cinema to see a movie with a bag of popcorn and a soft drink. I was so touched. What they wish is just something basic. I wonder whether I can fulfill their dream," Kwan says.

Wanting to take the blind to local movie theatres, Chang and Kwan approached AMC Festival Walk in Kowloon Tong for permission to show Kwan's film, for the blind.

"Our program has a small budget and we didn't have money to pay for the HK$8,000 fee for the screening," says Chang, executive producer for Dreams Come True.

Later Chan got HK$3,000 from the HKSB to share the cost, and Chang and Kwan raised the rest from their workmates "with a money box".

Hoping to promote movies for the blind, Chan invited some TV artists and the media to watch the film.

At 2 pm on June 11, the film was about to start.

TV artist Samantha Chuk Man-kwan, who heads Artiste Training Alumni Association, arrived at the screening with her peers to lend support. She says it felt a meaningful thing to do, to help the blind watch movies.

"I went to many film openings and those of my own films, but this is my most important screening ..." Kwan said, bursting into tears speaking in front of the audience.

"Films are not just to make money. They can be a blessing to society."

"I hope that we can help the visually impaired to see movies in local cinemas. Today is the start."

Holding a megaphone and standing on the steps next to the audience, Kwan, wearing his signature black cap, narrated for scenes in which there was no dialogue.

"A man walks up the stairs, he wears black. He sees a light before him, and a figure. Who is the person?" he told the audience.

In another scene, he says: "something unusual is happening. The street sleepers all gazed at a wall. It was a poster reading 'there are soccer games, meals and even beautiful ladies'."

"The rain is coming, and they all stand at the pitch and look very sad".

The audience is quiet listening to the descriptions.

The movie ends with the street sleepers finding hope and going to the homeless world cup.

Jason Ho Ka-leung, a visually impaired member of the audience stood up to thank Kwan.

"I am so happy and touched. I would like to thank director Kwan. I can't see a movie as a blind person, but he took me to a film. I hope that today is not the last time we can see a movie in a cinema."

Ho is calling on the government and the film industry to promote movies for the blind.

"I hope that all films will have sound tracks for the blind, and we can be barrier free to see a film."

Lo is urging DVD distributors, film producers, and the Hong Kong Film Archive to join together to help the blind see movies.

The United Nations' Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which took effect on the mainland, in Hong Kong and Macao in 2008, states parties shall "recognize the right of persons with disabilities to take part on an equal basis with others in cultural life".

The convention states that countries "shall take all appropriate measures to promote participation in cultural life" by ensuring provision of television programs, films, theatre and cultural material in accessible formats, and by making theatres, museums, cinemas and libraries accessible.

The LCSD spokeswoman says the provision of audio guides for each film at the Hong Kong Film Archive is not feasible "in view of cost implications".

A government spokesman for the Film Development Council would not comment on whether the council will take the lead in discussion of the matter or provide funding for cinemas and filmmakers.

But a council member and renowned filmmaker Mabel Cheung Yuen-ting, who produced the recent box-office success, Echoes of the Rainbow, supports the move to help the blind.

Coincidently she has offered to be a narrator for Chan starting in July.

"They are arranging several screenings of Echoes of the rainbow for the blind and I offered to be the narrator. It is my sincere hope that I can extend my service to the narration of films other than my own," Cheung says. She says she felt inspired to help the blind after one barrier free screening of her movie, The Soong Sisters, in Japan.

Cheung believes that it wouldn't cost much to make films accessible to the visually impaired in cinemas.

"I think some film makers wouldn't mind spending some time for this meaningful service," she says.

Cheung says she will take the matter to the Hong Kong Film Directors' Guild to discuss the idea.

Fanny Lam, executive officer of the Hong Kong Theatres Association, also says the group will discuss the idea.

Tessa Lau Siu-man, executive director of Broadway, AMC & Palace, says that a balance must be struck between cost and social responsibility.

"It is good that anyone can enjoy a movie. If it doesn't cost much, why not do it? But if it costs a huge amount of money, it is difficult for us to do it."

But both Lam and Lau say filmmakers have to take the first step or cinemas can't do it.

Emily Chan says that being able to watch films has helped her understand society and its trends. She has also learnt from narrations that "people can express their love through eyesight".

Walking out of the cinema, Tsui Yu-hang expressed feelings of hope.

"I am happy that I can close my eyes to see a movie. Kwan narrated it so well. I used my imagination to see the movie and don't need to worry about disturbing others."

(HK Edition 06/30/2010 page2)