A hunger for higher learning

Updated: 2010-05-29 07:31

By Kane Wu and Timothy Chui(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

|

Research postgraduate students from the mainland at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. edmond tang / china daily |

As Hong Kong kids stream to the job market clutching freshly acquired Bachelor's degrees, mainland students are becoming the dominant group among postgraduate students at the city's universities. Kane Wu and Timothy Chui report.

It came as a blow when Yin Wenting, a student from Shenzhen, was rejected in her application to attend the University of Hong Kong (HKU), the city's top university, five years ago.

Her most obvious option appeared an offer of enrolment from one of the top ten universities on the mainland but she was not satisfied.

Rather than enrol in the elite mainland university, Yin took her third option, to become a student at the Hong Kong Institute of Education. The quality of the education she could obtain in Hong Kong and the city itself were prime motivators in shaping her final choice. "It seemed such a dazzling cosmopolitan city to me at the time," she says.

Hong Kong's effort to become a regional educational power house is paying off. Education Bureau statistics show that the number of non-local students studying under University Grants Committee (UGC) programs doubled from its 2006 level to 8,400 in the 2009-2010 academic year.

HKU alone is getting around 9,000 applications every year from mainland students seeking enrolment in the university's undergraduate program. Fewer than 300 of those applicants - slightly more than 3 percent - are accepted.

"Hong Kong embraces a diversity of different cultures; it is the best choice for students who want to keep pace with the development of the emerging Asian markets while maintaining a global perspective," Isabella Wong, director of the China Affairs Office of the HKU, says.

The relaxation of rules for mainlanders applying for Hong Kong visas plays a big part in the influx of mainland students. In 2008, the Hong Kong Immigration Bureau started granting visa extensions of one year for mainland students who earn at least a bachelor's degree in a local university. That means students have time to look for a job. It's making it a lot easier for graduates to find work and settle down in the city.

"It's an open secret mainland students make up the majority of overseas students in Hong Kong so its pretty fortunate local universities have a ready supply of students nearby who are a boon to a school's rankings," says a business professor teaching at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who declined permission for her name to be published.

Undergrad Mary Wang Yueming says the perception is widespread that students can improve their career prospects back on the mainland, or even farther afield, if they obtain their degree from a Hong Kong university. She's from Harbin, in northeastern China's Heilongjiang province. Wang is studying business administration, accounting and finance in Hong Kong. After graduation, she hopes to move on to take a master's degree in the US or the UK to give herself a solid footing in the business world. Wang said the quality of education in Hong Kong was considered to be better than most schools on the mainland. English language instruction in Hong Kong also provided an advantage. She says local teaching methods are more flexible and interactive. The city's Western-style approach and general openness enhance the academic atmosphere, and learning seems to flourish, she added. In her view, this liberal approach encouraged a higher level of critical thinking and problem-solving skills compared to the more formulaic approach at mainland schools.

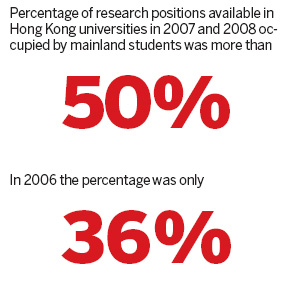

Mainland students are pretty much taking over postgraduate programs. It's a trend that's evolved over the past four or five years. UGC figures showing sharp incremental increases in the numbers of mainland students reveal the measure of mainland dominance. More than half of the 5,871 research positions available in 2007 and 2008 were occupied by mainland students. In 2006 mainland students represented only 36 percent of postgraduate enrollment, UGC statistics show.

Vincent Cheung, head of the Postgraduate Studies Administration at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), says the mainland contingent now comprises 70 percent of students enrolled in the university's research programs.

Cheung offers this possible explanation as to the reason local students have become the minority: the local students tend to complete their education as soon as possible and start earning money. "They might feel overqualified for the job markets with a master's or PhD degree," Cheung explains. "After all, it was only in the past decade that the government started supporting research in science and technology. The demand in the job market (for these graduates) is still limited."

By contrast, students who took their college education on the mainland are prepared to pay higher tuition fees here, because they see advanced education at a Hong Kong University as invaluable.

Twenty-year-old Tu Hua passed up an offer to study law at the Renmin University of China in favor of a master's degree in business management in Hong Kong.

Studying business in a financial center with internationally renowned schools seemed only common sense to the Guangzhou native. Hong Kong offers more international exposure than most mainland schools.

Even though tuition is higher in Hong Kong than on the mainland, the cost of attending a school here is still a good deal lower than at overseas universities in the West.

"Money is still one of the biggest barriers," he said, adding application, visa and financial requirements for undergraduates seemed to increase in proportion to the distance from home.

With mainland students becoming a rising force in local universities, distinctions between local and mainland students already are becoming blurred. HKU Faculty of Education Dean Shirley Grundy observed, "I suspect that as Hong Kong becomes more integrated into the country, especially the Pearl River Delta region, the distinctions between local and mainland students will become less meaningful."

Henry Wai, the registrar of HKU, thinks that as more and more Hong Kong companies expand into the mainland, locals will benefit from their exposure to their mainland classmates. "At least they speak better Mandarin than before," he says. "And with these mainland connections, they can get an edge when applying for jobs."

The long-term effect of the mainland influx on the whole seems even more rewarding, according to educators.

Cheung sees it from yet another perspective, "There are a great number of aging people in Hong Kong, which could be a potential threat to the social and economic sustainability of the city. If mainland students stay in Hong Kong to pursue their careers, they can help alleviate the problem." Currently, only 18 percent of the Hong Kong population are in the demographic window of post-secondary education. "It's a win-win situation," Cheung says.

Mainland students in Hong Kong are not only pursuing a higher standard of education, they want a better lifestyle after graduation.

"Never would I have become who I am today, if I hadn't come to Hong Kong," says Mao Mao, who graduated from the HKUST with a Bachelor's degree in Electronics and Computer Engineering and now works in the IT department of an investment bank. The tuition fees, HK$120,000 a year, are a huge investment for Mao's family, but it's paid off. "It took less than two years for me to earn the money I spent over all four years in the university. I currently have one of the best jobs among my high school classmates who went to universities on the mainland," Mao says.

Mao has just enrolled in a part-time master of science program in financial analysis at the HKUST. The program starts in September. "I hope to work as a research analyst or for a consulting firm while I am completing the courses," he says. "The city's dynamic financial sector offers so many opportunities. I see a bright future ahead."

Mainland students are strong competitors of their local counterparts in the job market. "One-third of the mainland students were in the top ranks of their classes," Chung Jah Ying, a recent local graduate from HKU says. "And in our program, the highest- income job was taken by a mainland student." Chung admits that those mainland students who can also speak Cantonese and good English apart from Mandarin "have a significant edge over us".

That's why the HKU's Wong has no worries about the job prospects of mainland students. "I haven't heard of a single student from the mainland who failed to find a job after graduation," she says. "These students are already the elite from the mainland. The overseas exchange programs we offer add to their global background. And with strong academic performance and language skills, they are favorites among employers."

Zou Chonghua, a division head at the Beijing-Hong Kong Academic Exchange Centre (BHKAEC) who came to Hong Kong 16 years ago, says that most of the researchers in the Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks are mainland graduates. A PhD holder from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Zou now organizes academic and research exchange programs between Hong Kong and mainland higher education and research institutions. "Talent from the mainland contributes greatly to Hong Kong's scientific research, which enjoys a worldwide reputation for its high quality," he says.

(HK Edition 05/29/2010 page2)