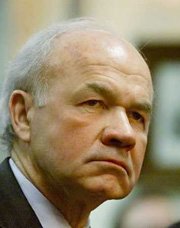

Former Enron Corp. Chairman and Chief Executive Kenneth Lay, who grew the company into an energy trading giant that became the ultimate symbol of corporate wrongdoing and greed, was

indictedon Wednesday and said he would surrender to authorities. Former Enron Corp. Chairman and Chief Executive Kenneth Lay, who grew the company into an energy trading giant that became the ultimate symbol of corporate wrongdoing and greed, was

indictedon Wednesday and said he would surrender to authorities.

Lay said in a statement issued Wednesday afternoon he had been indicted and would surrender on Thursday morning. Sources earlier said a federal

grand juryreturned a sealed indictment with

undisclosedcriminal charges for Lay's actions before the company fell into bankruptcy in December 2001.

On Thursday, Lay is to follow a

well-wornpath for former Enron executives: surrender to the FBI and then make his initial appearance before a federal

magistratejudge.

"I have been advised that I have been indicted. I will surrender in the morning," Lay said. "I have done nothing wrong, and the indictment is not justified."

Houston-based Enron was the nation's seventh largest publicly owned firm when it

unraveledin the final months of 2001 amid disclosures that it had used

off-the-booksdeals to hide billions in debt and falsely inflate profits.

Lay, 62, has

steadfastlydenied any wrongdoing.

Separately, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission plans to file civil fraud charges against Lay in Houston on Thursday morning, a source familiar with the matter said.

Lay, once a leading U.S. industrialist and close friend of President Bush -- who called him "Kenny Boy" -- now faces

felonycharges stemming from the Enron

debacle.

The charges come 2.5 years after the U.S. Justice Department began an investigation which has slowly climbed the corporate ladder to bring criminal charges against 22 former Enron employees.

Former Chief Financial Officer Andrew Fastow pleaded guilty in January and is cooperating with prosecutors who were aiming higher up the corporate ladder.

He helped prosecutors bring charges against Lay's

handpickedsuccessor, Jeff Skilling, who unexpectedly quit in August 2001, six months after becoming CEO.

The fall of Enron

touched offinvestigations that uncovered widespread financial fraud in corporate America and was followed by scandals that brought down giants such as accountancy Arthur Andersen, telecoms giants WorldCom Corp., now MCI, and GlobalCrossing and HealthSouth Corp.

Those bankruptcies and charges of criminal behavior in the boardroom eroded consumer confidence and helped send world stock markets into a yearlong

tailspin. In the wake of the scandals, strict new federal laws on corporate governance were enacted.

In a recent interview with the New York Times, Lay accepted responsibility for Enron's

demise, but said he had committed no crimes.

He said Fastow, the architect of Enron's financial house of cards, was largely to blame for the company's troubles.

"At our core, regrettably, we had a chief financial officer and a few other people who, in fact, mismanaged the company's balance sheet and finances and enriched themselves in a way that once we got into a stressful environment in the marketplace, the company collapsed," Lay told the Times.

Legal experts said that defense might not win over a jury, especially in Houston, where thousands of people were affected by the company's collapse.

Lay, as head of then Houston Natural Gas, led a 1985 merger that formed the modern Enron.

He became an aggressive political player who lobbied lawmakers such as Bush and his father, former President George H.W. Bush, to

deregulatenatural gas markets.

Generous campaign donations -- at one time he was the current President Bush's top contributor -- helped gain access to the halls of power.

Enron used deregulation to become a dominant force in electricity trading in the 1990s and served as a role model for dozens of other firms that

mimickedits no-holds-barred trading practices.

But the burgeoning merchant power industry imploded after Enron's collapse and the California power crisis of 2000-2001.

Lay was Enron's chief executive for most of the company's history, but handed the post to Skilling in February 2001.

Skilling suddenly resigned in August 2001 Lay resumed as CEO until he quit in January 2002.

Lay told the Times his personal fortune once stood at 0 million, but had dropped below million because most of his holdings were in now worthless Enron stock.

|