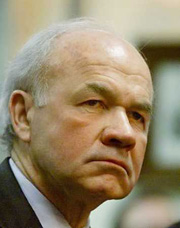

Former

Enron Corp. Chairman and Chief Executive Kenneth Lay, who grew the

company into an energy trading giant that became the ultimate symbol

of corporate wrongdoing and greed, was indicted

on Wednesday and said he would surrender to authorities. Former

Enron Corp. Chairman and Chief Executive Kenneth Lay, who grew the

company into an energy trading giant that became the ultimate symbol

of corporate wrongdoing and greed, was indicted

on Wednesday and said he would surrender to authorities.

Lay said in a statement issued Wednesday afternoon he had been

indicted and would surrender on Thursday morning. Sources earlier

said a federal grand jury returned

a sealed indictment with undisclosed

criminal charges for Lay's actions before the company fell into

bankruptcy in December 2001.

On Thursday, Lay is to follow a well-worn

path for former Enron executives: surrender to the FBI and

then make his initial appearance before a federal magistrate

judge.

"I have been advised that I have been indicted. I will surrender

in the morning," Lay said. "I have done nothing wrong,

and the indictment is not justified."

Houston-based Enron was the nation's seventh largest publicly owned

firm when it unraveled in the final

months of 2001 amid disclosures that it had used off-the-books

deals to hide billions in debt and falsely inflate profits.

Lay, 62, has steadfastly denied

any wrongdoing.

Separately, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission plans to

file civil fraud charges against Lay in Houston on Thursday morning,

a source familiar with the matter said.

Lay, once a leading U.S. industrialist and close friend of President

Bush -- who called him "Kenny Boy" -- now faces felony

charges stemming from the Enron debacle.

The charges come 2.5 years after the U.S. Justice Department began

an investigation which has slowly climbed the corporate ladder to

bring criminal charges against 22 former Enron employees.

Former Chief Financial Officer Andrew Fastow pleaded guilty in

January and is cooperating with prosecutors who were aiming higher

up the corporate ladder.

He helped prosecutors bring charges against Lay's handpicked

successor, Jeff Skilling, who unexpectedly quit in August 2001,

six months after becoming CEO.

The fall of Enron touched off investigations

that uncovered widespread financial fraud in corporate America and

was followed by scandals that brought down giants such as accountancy

Arthur Andersen, telecoms giants WorldCom Corp., now MCI, and GlobalCrossing

and HealthSouth Corp.

Those bankruptcies and charges of criminal behavior in the boardroom

eroded consumer confidence and helped send world stock markets into

a yearlong tailspin. In the wake

of the scandals, strict new federal laws on corporate governance

were enacted.

In a recent interview with the New York Times, Lay accepted responsibility

for Enron's demise, but said he had

committed no crimes.

He said Fastow, the architect of Enron's financial house of cards,

was largely to blame for the company's troubles.

"At our core, regrettably, we had a chief financial officer

and a few other people who, in fact, mismanaged the company's balance

sheet and finances and enriched themselves in a way that once we

got into a stressful environment in the marketplace, the company

collapsed," Lay told the Times.

Legal experts said that defense might not win over a jury, especially

in Houston, where thousands of people were affected by the company's

collapse.

Lay, as head of then Houston Natural Gas, led a 1985 merger that

formed the modern Enron.

He became an aggressive political player who lobbied lawmakers

such as Bush and his father, former President George H.W. Bush,

to deregulate natural gas markets.

Generous campaign donations -- at one time he was the current President

Bush's top contributor -- helped gain access to the halls of power.

Enron used deregulation to become a dominant force in electricity

trading in the 1990s and served as a role model for dozens of other

firms that mimicked its no-holds-barred

trading practices.

But the burgeoning merchant power industry imploded after Enron's

collapse and the California power crisis of 2000-2001.

Lay was Enron's chief executive for most of the company's history,

but handed the post to Skilling in February 2001.

Skilling suddenly resigned in August 2001 Lay resumed as CEO until

he quit in January 2002.

Lay told the Times his personal fortune once stood at 0 million,

but had dropped below million because most of his holdings were

in now worthless Enron stock.

|