---

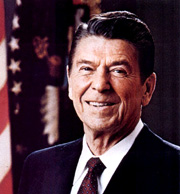

A captivating and elusive man, Ronald Reagan rose from lifeguarding

in Illinois to Hollywood and became one of our greatest presidents.

An intimate look at how he played the role of a lifetime ---

A captivating and elusive man, Ronald Reagan rose from lifeguarding

in Illinois to Hollywood and became one of our greatest presidents.

An intimate look at how he played the role of a lifetime

His timing, as always, was perfect.

Almost exactly 20 years after he stood before the aging soldiers

of D-Day on the cliffs of Normandy, saluting the warriors who had

saved democracy, Ronald Reagan died, quietly, in his house on St.

Cloud Drive in Bel Air last Saturday, ending his long and noble

battle against Alzheimer's disease.

"It was very peaceful," a family member said. "It

was time."

Word of Reagan's death came as the world was once again commemorating

the Allied victory over Nazi tyranny. As presidents and princes,

old soldiers and sailors, widows and grandchildren gathered on those

same wind-swept beaches last weekend, they, and America, were hearing

Reagan's words as they mourned his death. "These are the boys

of Pointe du Hoc," Reagan had

said on June 6, 1984, hailing the Rangers

who helped spearhead the liberation.

"These are the men who took the cliffs." Grown men wept

that day in 1984; Reagan's voice caught with genuine emotion. "The

men of Normandy had faith that what they were doing was right,"

he said, "faith that they fought for all humanity, faith that

a just God would grant them mercy on this beachhead-or

on the next."

He spoke with such grace, such conviction and such power that only

the most cynical observers recalled that Reagan himself had spent

World War II in Hollywood, making training films. That day at Normandy-and

all the other days of his remarkable public life-Reagan was doing

what he did best: making us believe in a vision of America as a

beacon of light in a world of darkness, as the home of an essentially

brave and good people. "We will always remember," he said

that long-ago day. "We will always be proud. We will always

be prepared, so we may be always free." Freedom-from self-doubt,

from the Soviet threat, from uneasiness about our national power

and capacity to do great things-was Reagan's gift to his country.

He was 93; for his devoted wife, Nancy, now 80, her beloved husband's

death ends a half-century love affair and a decade of anguishing

illness and caregiving. She may find some comfort in the nation's

outpouring of affection; few men

in our history have been held in such warm regard. This week Reagan

will receive a hero's farewell in Washington, lying in state in

the rotunda of the Capitol followed

by a funeral service at the National Cathedral. Then he will go

home again, back across the nation, to be interred on the grounds

of his presidential library in southern California's Simi Valley.

For Mrs. Reagan, it will be the final act of what she has called

her husband's "long goodbye." For the rest of us, the

passing of the 40th president marks the close of one of the great

American sagas: the rise and reign of the mysterious and elusive

Ronald Reagan.

He fought the good fight for years. Toward the end, in the late

1990s, he could only remember the beginning. As Reagan's memory

faded, the years seemed to fall away: the presidency, the governorship,

Hollywood, sportscasting. Among his sharpest recollections was his

youth in Illinois. In chats with guests in his Los Angeles office

and in bits of conversation with his family at home in Bel Air,

he would talk about learning to read newspapers on the front porch

with his mother, about playing with his older brother, Neil, about

setting off for the picture-perfect little campus of Eureka College.

And there were his early days on the Rock River, where he swam in

the summers and ice-skated in the winter. A picture of the river

hung in his retirement office in Century City, and visitors would

ask him about it. Again and again he would tell the story. "You

know, that's where I used to be a lifeguard-I saved 77 lives."

There had been a log, he went on, where he carved a notch for every

swimmer he rescued. "It was obviously an important part of

his life, something he cherished," an aide recalled. "Being

a lifeguard was ever-present in his memory." The image lingered

when everything else was disappearing.

The lifeguard would grow up to seduce and shape America. When Reagan

became president in January 1981, the country was suffering from

what his predecessor, Jimmy Carter, described as a "crisis

of confidence." After triumph in World War II and the boom

of the 1950s, postwar American optimism seemed to peak just before

John F. Kennedy's assassination. After Dallas came Vietnam and Watergate.

On Carter's watch inflation spiked, deficits soared, the Soviets

invaded Afghanistan and Islamic militants took 52 U.S. diplomats

hostage in Iran. Serious people began to wonder whether the presidency

was too big a job for any one man.

Then along came Reagan-nearly 70, the emotionally distant son of

an alcoholic Midwestern shoe salesman and a pious,

theatrical mother. A former movie actor who gave his only critically

acclaimed performance before Pearl Harbor, he was a sunny Californian

who amiably ducked his head while talking tough on bureaucracy at

home and communism abroad, pushing the nation's political conversation

to the right.

In the White House, Reagan proved a maddeningly contradictory figure.

An eloquent advocate of traditional values, he divorced his first

wife and was often estranged from his children. A fierce advocate

of balanced budgets, he never proposed one. A dedicated anti-communist,

he reached out to the Soviet Union and helped end the cold war.

An icon of button-down morality, he led an administration beleaguered

by scandals. A man capable of nuanced thinking, he strongly believed

in Armageddon.

He mangled facts; caricatured welfare recipients; opened his 1980

presidential campaign in Philadelphia, Miss., in the county where

three civil-rights workers had been murdered for trying to overthrow

Jim Crow; presided over a dark recession in 1982-83; seemed uncaring

about the emerging HIV/AIDS crisis, and, in the Iran-contra scandal,

came perilously close to-and may have committed-impeachable offenses.

Reagan, then, should have been as divisive a politician as Bill

Clinton or George W. Bush-a man about whom the nation was closely

and bitterly split. And while many people were consistently critical

of Reagan, he still left office with a 63 percent approval rating.

The roots of our own age's attack politics and ideological divisions

lie in the Reagan years, yet the man himself seemed to dwell just

above the arena, escaping widespread political enmity.

What was his secret? His personal gifts were enormous and helped

smooth the rough edges of his rhetoric and his policies. Reagan

was witty, eloquent and bold. Wheeled into the operating room after

being shot in the chest on March 30, 1981, the president looked

up at the doctors and murmured, "Please tell me you're all

Republicans." Coming to after the surgery, he whispered to

Nancy, "Honey, I forgot to duck." At the Brandenburg

Gate in 1987, he stood in the heart of divided Berlin and

cried, "Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, tear

down this wall." And eventually it was gone.

|

|

note:

|

captivating: 迷人的,有魅力的

Alzheimer's disease: 阿尔兹罕默氏病(老年

痴呆症)

Pointe du Hoc: 霍克角

ranger: 突击队员

spearhead: 先头部队

beachhead: 登陆场

outpouring: 倾泻,流露

rotunda: 圆形大厅

Watergate: 水门事件

pious: 虔诚的

Brandenburg Gate: 勃兰登堡门

|

|