Ethnic Experience

Tibet's best-kept secret

By Qi Xiao (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-26 09:52

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

|

|

Nedong county, southeast of Lhasa, is an oasis of tranquility and home to the region's first palace as also its first village, as Qi Xiao discovers

Riding an early morning bus with a dozen Tibetans in Nedong county feels surreal. Listening to them make small talk in their own language feels even more unreal. While the morning ride is commonplace for the locals going about their everyday chores, it is a whole new experience for an outsider like me in the very heart of Tibet autonomous region.

August is the harvest season in Tibet, and the weather is most pleasant. The cool climes offer a perfect escape from the wilting heat of other parts of the country. Mysterious Tibet becomes even more attractive to travelers.

From the crowded capital city Lhasa to the sparsely populated western Ali area, hordes of tourists from home and abroad can be seen everywhere. Hotel rates as well as prices of admission tickets to popular tourist draws, such as Potala Palace, also begin to climb.

The oasis of tranquility in Nedong county of Shannan prefecture - an area to the southeast of Lhasa known as the cradle of Tibetan history and culture - offers a welcome respite. Although Nedong county, Shannan's cultural and administrative center, is no more than 200 kilometers from Lhasa and about 100 km from the region's major airport, it is not known to many tourists.

Indeed, driving half an hour to the south along the two-lane asphalt road, which leads to the China-India border area, I do not see a single tour bus.

When the bus arrives at its final stop, only a handful of visitors can be seen and some are already trudging along the steep mountain path and halfway to their final destination, Yambulakang, the first-ever Tibetan palace.

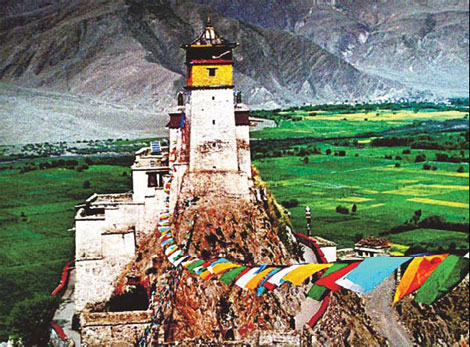

Perched precariously on the top of Mount Tashitseri overlooking the Yarlung River valley, considered the place of origin of Tibetan civilization, the palace was built more than 2,000 years ago by Nyatri Tsenpo, literally "King on the Neck", the first Tibetan king.

Legend has it that, one day, a strange-looking young man descended on the valley. When the tribal leaders asked him where he had come from, he just kept pointing to the sky as he could not understand them. The chieftains decided he had been sent from heaven, hoisted him on their necks and crowned him Nyatri ("neck" in Tibetan) Tsenpo ("king").

Historians later said Nyatri Tsenpo was actually from Bomi county in southeastern Tibet.

For those looking for magnificence, the first impression of this palace can be quite disappointing. One is apt to wonder how this three-story structure could have been home to Tibetan kings and later also served as the summer palace for the mighty Songtsen Gampo and his wife Princess Wencheng.

A local peddler, who declines to reveal his name, becomes philosophical as he ponders this question.

"Everybody jostles to get into the Potala Palace, which is perfectly understandable given its grandeur and status," he says. "But the Potala, and various later palaces for that matter, are in fact just a series of Yambulakangs."

Visitors will quickly recognize Yambulakang's strategic location - it is easy to defend and well-positioned to withstand the frequent mudslides that used to plague the Yarlung River valley - and marvel at the wisdom of Nyatri Tsenpo. No wonder he was able to unite the warring tribes in this area and become king.

Most will also probably end their trip here. It is natural that they will look up at the palace where kings used to live, rather than down.

But it is right at the foot of the mountain atop which Yambulakang sits, on the other side of the regular tourist route, that Tibet's first agricultural plot and its first village Yarlung Suoka lie.

To the south of the village, right beside the asphalt road, two cows graze nonchalantly. On one side of it is a stone tablet covered in rags and bearing an inscription in Tibetan, Chinese and English attesting to its historical value.

On the other side of the road, wheat and Tibetan barley lie neatly bundled on endless fields.

But for the distinct Tibetan-style brick house in the village, this could well be a scene from the American Midwest.

Under the early afternoon sun, the village, boasting about 20 households, seems totally deserted, barring the occasional dog barking or a rooster crowing. But as I turn a corner, I see a group of villagers in a big courtyard, leaning against a short wall, sitting in the shadows of two roadside trees and sipping their afternoon tea.

"This is my home," says 39-year-old Geduo, although I see no door anywhere - only walls.

They are all descendants of the first villagers.

"We rarely see any visitors here," 55-year-old Dawa Ciren says. "They always go to the palace."

He says they have been living here for as long as he - and his father and grandfather, for that matter - can remember.

"A hundred generations?" he mutters to himself. "I don't know."

Except for the tractor in Geduo's courtyard and a few other harvesting machines, the village looks like something out of antiquity.

But the lack of modernity hardly seems to bother its residents, not even 24-year-old Yangjin, the youngest of the group, who has returned home after completing high school.

Asked why she had not pursued further studies and gone to, say, Tibet University in Lhasa, she says: "It's not that I don't want to - it's just that I love my farm life more."

Geduo interjects and points to his courtyard and the fields across the road. "This is our university," he exclaims, eliciting a chorus of hearty laughter from the others.

It is barely 3 in the afternoon, but Geduo and his companions are already preparing to return to their "campus".

For their daily lives, especially farm work, they still depend largely on the rising and setting of the sun - the watch being a superfluous accessory.