Society

Shantytowns face hard home truths

By Fu Lei (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-13 07:43

|

Large Medium Small |

Waiting game

|

|

A corner of Cha Kwo Ling in eastern Kowloon that is home to 3,000 people. The area has long been a major settlement for the Hakka ethnic group and mainland migrants. [China Daily] |

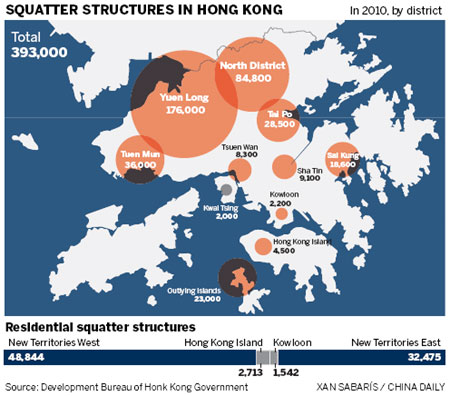

A watershed for Hong Kong's shanties came in 1982 when the regional government conducted a survey of all existing squatter structures, the materials that went into them and the surrounding neighborhoods.

No new shanties have been permitted since then but dwellings built prior to that are tolerated until redevelopment begins.

Qualified residents of shantytowns have been told they will be re-housed in public rental apartments; however, such properties are in short supply.

Almost one-third of Hong Kong's 7 million residents live in its 710,000 public rental homes, according to official statistics.

In his annual policy address last month, Donald Tsang, chief executive of the SAR, vowed that the government will shorten the average waiting time for a public accommodation to three years by allocating enough land for 15,000 new apartments every year.

Ip said the government has so far "ceased its large-scale eastbound development in New Kowloon, which started in the 1930s and lasted for half a century". (Cha Kwo Ling lies to the far east of New Kowloon.)

If the government does redevelop Tse's village, residents would be given two years' credit by the housing authority, which would theoretically slash the waiting time to about 12 months. However, not everyone will be eligible.

"To qualify, at least half of an applicant's family must have lived in Hong Kong for seven years," said Ng Yin-cham of the Neighborhood Advice Action Council, a government-backed organization offering consultancy services to the "most helpless people".

"A considerable number of dwellers are migrants from the Chinese mainland," he said. "Their wives and children may have come to Hong Kong later and have not been here for seven years."

Tse has lived in Hong Kong for decades but most of her children and grandchildren are now in Guangzhou, capital of South China's Guangdong province.

In fact, the 65-year-old said that, despite the hardships, she does not want to move from the community she has laid down her roots.

"My house is cozy, and I pass the time of day with my neighbors," she said, smiling. "In a public housing estate, the doors are all shut. People don't even know each other."

Every afternoon, locals flow into Tse's cafe for snacks, drinks and conversation. Inside are six wooden tables fixed to the floors, while among the decoration is an old, yellowed advertisement poster.

The shantytown offers more than just a relaxed ambience, though. "The location is ideal: sitting on a hill and facing the sea," said Tse. "Transportation is also convenient."

Good with the bad

Yet, for every pro there is a con. Although the four-lane highway running in front of Cha Kwo Ling has several minibuses carrying commuters to the two nearby subway stations, the majority of vehicles using the route are heavy-duty trucks carrying concrete and steel containers.

A lot of the traffic is heading to the metal recycling plant at a walled quay on the other side of the road or a small paper recycling center in the shantytown.

The proximity to the harbour, while providing a costal vista and balmy breezes, also exposes the fragile shanties to the gales that hit Hong Kong every summer and autumn.

Like most shantytowns, the village does not have even basic facilities, such as a gas supply, which means residents have to use liquefied petroleum gas cylinders for cooking and bathing.

Arguably the worst problem is the lack of private toilets. The underground drainage pipes beneath Cha Kwo Ling are too narrow for human waste, so locals use public toilets on the outskirts.

"Only those who ignore the interest in public health would build indoor toilets (here)," said a 72-year-old woman who declined to give her name. "The hygiene (in the village) is not good in general. My tin house gets stifling in the summer."

The woman, who settled in the area after moving from the Chinese mainland in 1962, said she and her 80-year-old husband have recently applied for public rental housing.

With densely packed buildings, narrow passages and highly flammable building materials, fire hazards abound in Cha Kwo Ling.

"We have fire accidents almost every year," said Tse, whose village witnessed three fires in just one month in 2006, leaving hundreds of residents homeless.

It was a sweeping fire at a settlement in Shek Kip Mei in late 1953 that displaced some 53,000 people that prompted the then-colonial government in Hong Kong to introduce the public housing system.

Despite the danger, Tse insists the only thing that will make her abandon her house is "if it is demolished".

Like most others in the village, she and her husband would be unable to afford the cost of living in other areas of the SAR, let alone afford the rent on another cafe.

"Even public rental flats will charge us," said Wu Wai-yuk, a mainlander who arrived in Cha Kwo Ling in the 1980s. "I'd rather save the money."

"Zi li geng sheng", she said, a slogan widely known among those born in the era of former leader Mao Zedong that roughly translates as "rely on yourself to change your own life".

"I don't pin my hope on others," added Wu.