Profiles

Reporter's Notebook: Being Somali

By Hu Yinan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-12 09:33

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

Their countrymen are now better known to the world as desperate adventurers on the high seas. But for many Somalis living in Kenya, everyday life can be an adventure, as China Daily's Hu Yinan finds out.

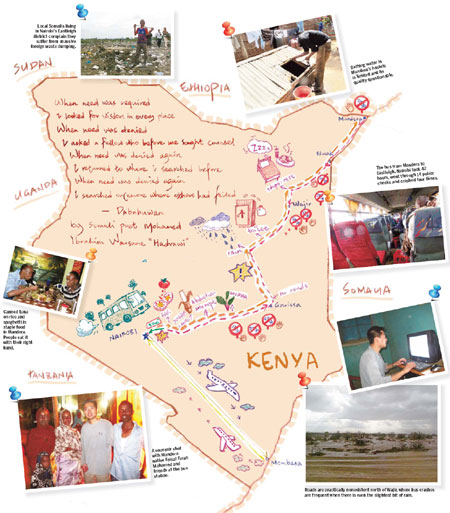

The trip to Kenya, to investigate the plight and status of Somalis living in Kenya, took a month of planning. After intensive research, I sent out more than 100 e-mails to local administrative bodies, foreign NGOs, analysts and reporters. Only three bothered to reply, and in the end, I did not use any of them. I met all the sources in my story on the ground. Luck, to be honest, played a big part. I only had nine days in Kenya. In order to talk to Somalis living in communities in Nairobi's Eastleigh neighborhood and the northeastern town of Mandera which borders Somalia, as well as a key source in the eastern port city of Mombasa, my timing had to be very precise. I also had to meet various other sources within the tight deadline.

|

Refugees are being pushed into the arms of radicals, Hu Yinan reports from Africa.

|

So early on the morning of Nov 9, I boarded a bus in Eastleigh with nothing more than a backpack and a little money, determined to travel alone to Mandera, where even UN staff members never leave their quarters without armed escort.

My top concern was never about security, but time. I was expected in Mombasa for a face-to-face interview at noon on Nov 13, and in Nairobi for two other interviews the following day. The bus to the border takes 30-odd hours and the return trip takes even longer, with police roadblocks for human-trafficking checks. It meant I had to get a bus ticket the very night I arrived.

The result was fruitful, among other things. Aside from learning what was needed for the stories I wanted to write, I escaped an abduction attempt in the first hours of my trip with the help of newly met friends, in whose company I made it through hours of anti-terrorism police questioning in Mandera.

There are no proper roads northeast of Garissa, capital of the North Eastern Province, but that didn't matter. The 14 roadblocks on the 42-hour ride back, and a road accident that triggered instant armed police response, helped me understand better what it meant to be a Somali.

For me, coming and leaving on a chopper and talking to "those who are authorized to speak with the media" in a fortified compound for an hour or two does little to explain the complexity of situations in any part of the world.

It is my belief that investigative reporters are duty-bound to be at the scene of what they're trying to uncover.

I believe that by taking the initiative, it is possible to reclaim the journalistic integrity lost to many in the profession.

The graphic, photographs and text try to recapture bits and pieces from this unique experience from Nov 9 and Nov 13.

I am indebted to the China-Africa Journalists' Study Tour Program arranged by the University of Witwatersrand's school of journalism in South Africa, which made my trip possible.

Hu Yinan's story, "Stark reality in a Somali community", was published on Dec 6 in China Daily.