Society

Cittaslow names Yaxi China's 'slow city'

By Shi Yingying (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-05 08:12

|

Large Medium Small |

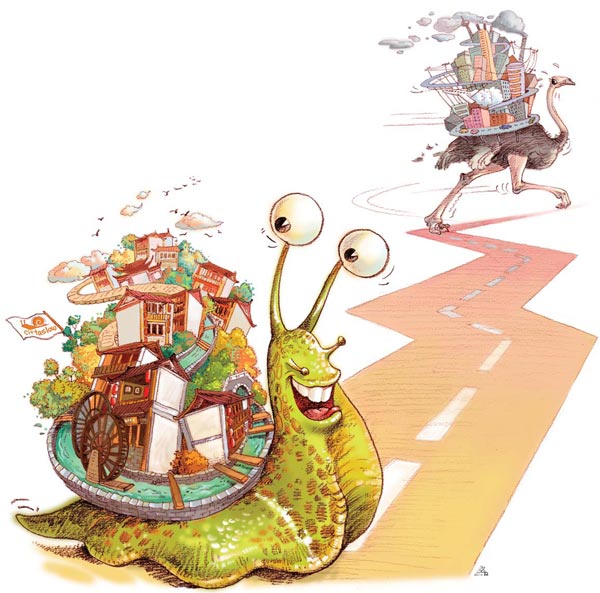

Cittaslow has discovered China, and it is awarding a little village in Jiangsu the title of "slow city". Shi Yingying looks at the rewards and possible repercussions.

The bored teenagers of Gaochun are impatient with the leisurely pace of hometown life. For them there is no nightlife to speak of, no bright lights, no excitement and they cannot wait to grow up and leave for the urban attractions of the big cities. But it is this laid-back lifestyle that has attracted international attention. At least, a quiet village within Gaochun county has come under the spotlight. Yaxi village, population 20,000, is about to be designated China's first "slow city" by Cittaslow, the sustainable lifestyle movement that first surfaced in Italy 11 years ago. Yaxi's nearest "sister city" in the Asia-Pacific will be Matakana, a little town in New Zealand's North Island where organic practices are a part of everyday life ?from the farmer's market to its vineyards, from its neighborhood café to its seafood restaurant.

At home, the residents at Yaxi are unfazed and pretty much unimpressed by the honor. To them, life has been like this for as long as they can remember.

"Slow city? That sounds like us," says 81-year-old Mei Weibing, whose shoe shop in Gaochun's Old Street has been around for more than 50 years.

Mei does not believe in mass production and three of his sons and their wives help out in the family business, learning the vanishing trade in the process. Every cloth shoe is painstakingly hand-stitched and Mei proudly declares, "I spend three days making one perfect pair of shoes."

It is this pride and spirit that first impressed Cittaslow, and the coming award is only a confirmation of the concerted efforts to preserve an old-country, small-village atmosphere where growth is limited, chain stores are discouraged and civic life revolves around a close-knit society.

Here, growing old gracefully is natural.

Unlike the retirees in urban centers who find too much time on their hands, Mei is too busy to be bored.

"I learnt how to make shoes when I was 13," says Mei. "I picked up the skill in the countryside while hiding from Japanese soldiers during the war and I have used this skill all my life." But, things are changing. It takes longer to make a pair of shoes now.

"Hand-stitched soles are no longer available in the local market, and that means I have to make them from scratch," says Mei. A radio keeps him company as he works and he proudly tells us the local station has just started all-day broadcasts from November.

Nobody living in this little county had heard of Cittaslow or the words "slow city" before this.

"The first time I heard the term was last July, when the vice-president of Cittaslow, Angelo Vassallo, visited Yaxi village," says Zuo Niansheng, the chief editor of local newspaper Gaochun Today.

"Vassallo was deeply impressed by this village's natural and cultural resources and said it perfectly fitted the requirements for a slow city," says Zuo. "That was how Yaxi became connected with Cittaslow."

Cittaslow was founded in Tuscany, Italy in 1999. It was a spin-off from the Slow Food movement which started, also in Italy, in 1986 as a protest against the first McDonald's opening near the Spanish Steps in Rome. The movement championed a return to healthy, nutritious home-grown, home-cooked food.

Slow Food has since expanded globally to more than 130 countries. Its mission has also broadened to include the promotion of sustainable foods and local small businesses, and the localization as opposed to globalization of food production.

It has spurred awareness in reducing carbon footprints of food logistics, such as reducing food miles - encouraging consumers to buy and eat locally produced meat and vegetables.

Cittaslow is an expansion of the Slow Food movement, and it actively advocates a lifestyle that is sustainable, that will improve quality of life, and will preserve cultural and culinary heritage.

Both movements share the logo of an orange snail, an icon increasingly recognized globally. There are now 135 accredited slow cities in 24 countries across the world.

"In China, we will start with Gaochun," says Cittaslow chairman Pier Giorgio Oliveti. "Slow city is not a Europe-centered project, it is for the planet."

The paperwork to add Gao-chun's Yaxi village to the list is in progress. Oliveti says he worked for three years to clear Colombia's Pijao town to make it an official slow city. It will earn its final accreditation in March next year.

"The criteria is very selective at the moment, and no town or city with more than 50,000 residents can be called a slow city," says Oliveti.

Yaxi village, with its 20,000 residents and 49 square kilometers of organic tea, Chinese herbs and orchards, fits the bill perfectly.

The Slow City must also be committed to protect and maintain the natural environment as well as promote a sustainable way of development - all of which are the current strategies adopted in Gaochun. "We've been doing this for years," says Zuo.

But the Slow City label has drawn criticism from some quarters, who see it as further proof that Gaochun has walled itself off as an isolated enclave.

"The county is surrounded by Gucheng Lake, Shijiu Lake and Shuiyang River," says Zuo. "In ancient times, we used to be a famous trading port as merchants from Anhui province congregated here to do business. But with the advance and development of land transport, we were left behind."

Wang Hongtao, who comes from a farming family in Yaxi village, says he probably has a higher happiness index than those living in big cities like Beijing or Shanghai. He has another take on the laid-back life.

"We are homebodies. We love our hometown and we are not interested in moving to big cities in pursuit of the so-called 'better life'. I guess there are two sides to the coin. The economy suffers because of this."

But being awarded the Slow City tag may also have its flip-side, if things are not carefully managed. Tourism is set to boom. Already, a new resort villa has opened and a new tour route to Yaxi is already in operation - all prepared for the potential rise in visitors.

How do you manage the floodgates?

"We want people to come, but we don't want that many people to come," said Marilyn Larden from the non-profit Sustainable Travel International at last month's China International Travel Mart in Shanghai. Say that again?

"We have to know what our environmental limits are before we promote the places of interest. The only way to do that is to know the bottom line. To understand, for example, what cultural elements you have, and how much it would cost in the carbon perspective," said Larden.

The secret, she says, is to know how to manage the process before it gets out of hand.

The Chinese has always been masters at unraveling the mysteries of the Middle Way, but the first Slow City in China will have to draw on all the wisdom of the sages if it is to tread the fine line between preserving a sustainable lifestyle and being swallowed by the inexorable swathe of progress which may come with the coach-loads of tourists all eager to visit China's first Slow City.