Society

From the height of success to the low of uncertainty

By Hu Yongqi and Zhang Leilong (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-25 07:40

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Huang Liang (center), 13, sits with other wushu trainees during a break from practicing a routine at Shaolin Temple Martial Arts School in the city of Dengfeng. Most students said they hope to become coaches after graduating.[Photo/China Daily]

|

|

Wushu student Zhu Ceng, 15, practices a split jump at the sacred Shaolin Temple on Songshan Mountain.[Photo/China Daily]

|

Martial arts students face the foe of doubt after graduation. Hu Yongqi and Zhang Leilong report from Dengfeng.

Zhao Peiyu felt like he was on top of the world - and it was not because he was suspended almost 80 meters off the ground by steel wires.

|

Chen Tao, a 15-year-old monk, practices martial arts at the Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng city, Henan province, in this file photo. [Photo/China Daily]

|

On the night of Nov 12, the 19-year-old was among more than 1,600 kungfu students who performed at the opening ceremony of the Guangzhou Asian Games.

"We travel a lot to perform in different places but this time we represented the country's youth," he said proudly, pointing at the Asian Games logo on his T-shirt. "We strived to make it the most impressive show we could."

It is not the first time Zhao has taken center stage at a major event. His school, Tagou Wushu Sports Academy, also helped open the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

However, back home in Central China's Henan province, the teenager's mood was less upbeat. The fleeting excitement in Guangzhou had been unable to ease his growing fears about the future.

"I don't know where to go now I've graduated," said Zhao, who, after training in the Chinese martial art of wushu for more than seven years, feels he is only qualified to "be a coach or join the army".

Like thousands of others at secondary vocational schools in Dengfeng, one of the spiritual homes of wushu, Zhao's schooling in standard subjects like Chinese, mathematics and English has taken a back seat to improving his acrobatic and kungfu skills.

On a regular day, he gets up at 5 am to practice zuigun, a stick-fighting style, for roughly two hours before breakfast, usually a steamed bun and porridge. After half a day of classes, he returns to the training area until the late evening.

"Hours of training on the playground is a real test for juveniles," said Zhao.

At his age, most are talking about another type of test - the gaokao, the national college entrance exam that can potentially make or break a student's job prospects. Zhao is unlikely to ever sit the exam and has little idea about his options.

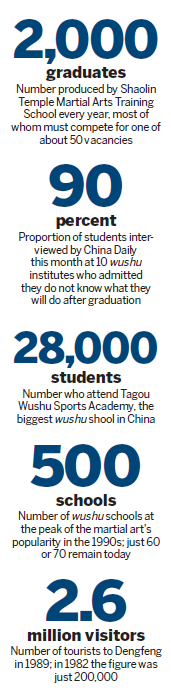

At least 90 percent of the students interviewed by China Daily this month at 10 wushu institutes admitted they do not know what they will do after graduation.

Zhang Xuemin, head coach at the city's Shaolin Temple Martial Arts Training School, said only three or four of its students continue their education at college every year.

In between performing at events home and abroad, most youngsters pin their hopes on earning jobs as coaches. Competition is fierce, however.

Shaolin Temple School has 260 teachers, mostly former students, and every year roughly 2,000 new graduates fight over just 50 vacancies on its staff.

If they fail to win spots at college or become coaches, the only other option is the army, said the school's deputy director, Men Zhendong. "The worst case scenario for graduates is to work as security guards," he added.

Men agreed that half a day of study is not enough to prepare youngsters for life after school, but then again many parents are unconcerned. He argued most children are sent to wushu schools to learn discipline, not book smarts.

"Most trainees at these schools were hard to handle at home," said director Zheng Hongqi, Men's boss. "Parents need an institute to take care of (the children), so they can dedicate their time and energies to making a living."

Coaches at Tagou Wushu Sports Academy, the biggest in China, also revealed that the vast majority of its 28,000 students were "problem youths" sent there to be "straightened out".

|

Cheng Yangyang (right), 18, prepares to take a heavy blow from his classmate's stick during a qigong training session at the Shaolin Temple Martial Arts Training School in Central China's Henan province. [Photo/China Daily]

|

Problem children

One of them was Zhao Peiyu. He grew up in the suburbs of Anyang, also in Henan, but was enrolled by his family at Tagou in 2003 because he "was too naughty".

His previous two years at a regular school were filled with on-campus fights and constant warnings from teachers about his behavior.

"I couldn't stand it (at Tagou) the first few months," he said. "Practicing in the heat of the afternoon sun left my arms and neck badly burned."

Most wushu apprentices in Dengfeng fall into three categories: countryside children left behind by migrant workers, children of single parents and children born out of wedlock. According to Chinese psychologists, these groups are all at risk of developing anti-social tendencies, such as over-aggressive attitudes or extreme shyness.

Based on estimates by staff members at all 10 schools visited by China Daily reporters in November, more than 70 percent of their students are from rural families.

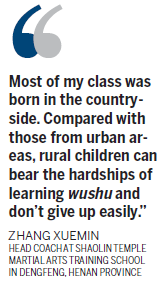

"Most of my class was born in the countryside," said coach Zhang at Shaolin Temple School, which has 10,000 registered students and is funded by the world-famous Shaolin Temple.

"Compared with those from urban areas, rural children can bear the hardships of learning wushu and don't give up easily," she said.

One initial hardship is coming to terms with the militaristic management style at wushu institutes. Unlike regular schools, students are often banned from leaving campus on weekdays and even need permission from teachers before they are allowed to leave on weekends.

When China Daily reporters visited Songji Wushu School on Saturday Nov 13, some of its 110 students could even be seen painting railings outside a four-story dormitory building.

| ||||

Yao Yuqing, director of its general office, defended the decision to get youngsters to decorate for free by arguing that they "had nothing else to do on weekends".

The school's website, which features many pictures of the Shaolin Temple but few of its modest classrooms and dirt-covered basketball court, states the annual tuition fee is 1,600 yuan ($240). However, students said they had been charged almost double that.

Yao refused to comment when asked about the price difference or whether the school is fully qualified to teach. Calls to the Dengfeng's wushu administration office also went unanswered.

Men at Shaolin Temple School said he believes the strict conditions, coupled with "peer pressure", can help troubled youths learn to "behave better and live independently".

"The schools are helpful to a stable society," he added.

In fact, wushu schools have become particularly helpful to the parents of illegitimate children. As these children are often unwelcome among Chinese families, many are unable to go home during national holidays, such as Spring Festival, and are forced to pay extra to stay in their dormitories.

Shaolin Temple School teaches 500 to 600 illegitimate children, according to Men. He would not reveal the charge for the "overtime care" but explained many parents are happy to pay so they can have a "comfortable holiday".

Management style

Wushu was born on the sacred Songshan Mountain, where the Shaolin Temple is located. Although the martial arts lost popularity during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), the hit movie Shaolin Temple brought it back to the public's attention in 1982.

By the end of the decade, visitors to Dengfeng soared from just 200,000 a year to 2.6 million.

The boom inspired the city's residents to open wushu schools and, at the peak in the 1990s, there were up to 500 institutes. Today, just 60 or 70 remain, with most teaching fewer than 1,000 students.

Most schools were originally opened by State and provincial wushu champions and then usually passed on to their sons. Small institutes with fewer than 100 students are still like family workshops, but major ones are run as corporate enterprises, with decisions made by a board of directors.

"As wushu schools are basically private, it makes sense that sons take over their fathers' businesses," said Niu Ziming, assistant training manager at Shaolin Temple School. "But the corporate management does good to our long-term development."

In the school's performance hall nearby, about 20 students were entertaining dozens of visitors with a dazzling display of acrobatic fighting skills.

Huang Liang, who at 13 is the youngest in the team, contorted and performed a standing split, while his classmate Long Shuang was suspended in the air on three sharp spears strategically placed underneath him.

"Wushu takes patience. You have to do the same action millions of times," said Zhao Peiyu at Tagou Wushu Sports Academy. "It's about resolve and perseverance."

For many wushu students without the necessary skills to survive in China's tough employment market, perseverance could be vital.