Society

Antibiotics: How nation got hooked

By Li Li (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-09 07:16

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Parents for their children to be attached to intravenous drips at the Xiangfan No 1 Hospital in Xiangfan, Hubei province, on Oct 26. Overuse of antibiotics has become a big problem in China. Gong Bo / for China Daily |

When Yu Liya's month-old daughter was diagnosed with pneumonia in September, she reluctantly agreed to let doctors put the child on a course of third-generation cephalosporin.

"The doctors said they weren't sure if the cause of the illness was a bacterial infection," said Yu, 27, who was both relieved and angered when test results a week later showed no evidence of such an infection. "My daughter could have recovered without antibiotics," she complained.

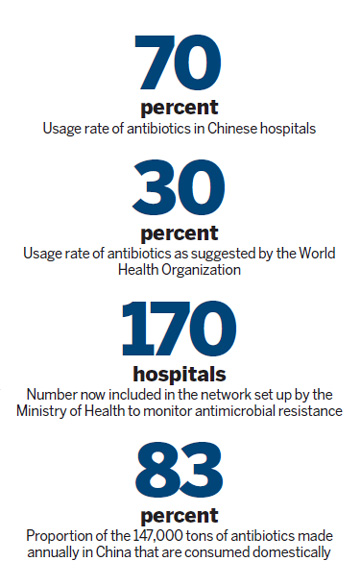

With a hospital usage rate of roughly 70 percent nationwide, more than double the level recommended by the World Health Organization, China is now a nation "addicted" to antibiotics.

Health experts say this rampant abuse is not only increasing the risk of superbugs, such as the NDM-1 strain that hit the mainland last month, but is also leading to more babies being born who are resistant to powerful medication.

At Chongqing Southwest Hospital, where Yu works, pediatricians said they have already found many newborns are resistant to antimicrobial drugs, which work against disease-producing micro-organisms.

"It says in my medical school textbook that streptococcus pneumoniae, which causes pneumonia, is sensitive to penicillin," said doctor Wang Yang. "But the bacteria has long beaten penicillin, so we have to prescribe more advanced antibiotics to the children."

Shi Yuan, chief physician of pediatrics at Chongqing Daping Hospital, added he has noticed a similar trend among the babies of women who have overused antibiotics during pregnancy, suggesting the possibility of intrauterine infection.

|

|

Examples of antimicrobial-resistant youngsters are now widespread, resulting in even simple conditions becoming difficult to treat.

"I know that in the United States pediatricians usually avoid giving children antibiotics. That's because they have a cleaner environment," said Zhou Zhongshu, head of pediatrics at China-Japan Friendship Hospital in Beijing. "We use antibiotics and even advanced antibiotics on our children because we are forced by our environment, which contains antimicrobial-resistant bacteria."

The situation, experts say, is highly alarming, especially as many pathogens (disease-producing micro-organisms) can now successfully battle antibiotic agents.

Gan Xiaoxie is a researcher at Chongqing Cancer Hospital's clinical laboratory, which conducts drug sensitivity tests on blood and phlegm samples. She explained that, 15 years ago, a condition like Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, which causes skin infections, was sensitive to penicillin, "but now we need to kill it with a combination of ultimate-level antibiotics".

"Macrolides (antibiotics), which successfully lowered the death rate from pneumonia three decades ago, are just not that effective anymore," added Tang Taiqin, a professor of pharmacology at Jinan University's No 1 Hospital in Guangzhou, Guangdong province.

|

|

Cure on demand

But how did China develop this addiction to antibiotics?

To some extent, patients must share the blame. Doctors at several hospitals told China Daily they are often put under extreme pressure by people demanding "the quickest cure".

"Today, patients are impatient," said Wu Shuai, an outpatient doctor at a hospital run by the Red Cross Society of China in Zhaoqing, Guangdong. "Many of them come and request antibiotics straight away. They expect to see an immediate effect."

Facing such opposition, many medics cave in and prescribe unnecessarily strong antibiotics, he said.

Zhaoqing is just two hours' drive from Hong Kong and Wu explained that many of his patients are businessmen and women from the mainland who return for treatment as antibiotics are tightly controlled in the special administrative region.

Sacrificing safety for speed can result in dire consequences, though. Liu Jianmin, for example, had never visited a hospital before he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

"Whenever I was sick, I just went to a drug store and bought whatever antibiotics the salesperson recommended," said the 58-year-old.

The farmer from Luobei county in Northeast China's Heilongjiang province is now in Beijing receiving treatment, which doctors say is being hampered as drug sensitivity tests have shown he is antimicrobial-resistant.

However, patients are not professionals and many health experts insist doctors must shoulder the responsibility for the overuse of antibiotics.

"One more treatment is one more way of making money for the medical department and one more bonus," said Wan Ruijie, a doctor at Chongqing No 1 People's Hospital, explaining why antibiotics are prescribed so often.

But money is not the only problem; there is also a shortfall in applied knowledge.

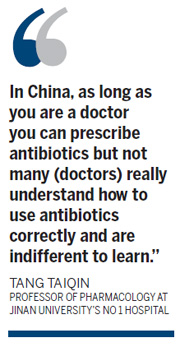

"In China, as long as you are a doctor you can prescribe antibiotics," said Tang at Jinan University's No 1 Hospital, "but not many (doctors) really understand how to use antibiotics correctly and are indifferent to learn."

The only official regulation on antibiotic use is the 2004 Guiding Principles for Clinical Application of Antibacterials issued by the Ministry of Health. Yet, Tang argued that the guide is too rough.

"A more detailed guideline with enforcement mechanisms is needed," he said. "The power to prescribe antibiotics should be clearly laid out."

As farmer Liu can testify to, the easy access to antibiotics through drug stores and private health centers is also a major contributing factor. Although the government forbids the sale of the medicine without a prescription, the rule is generally ignored.

The difference in antibiotic use between Chinese hospitals and the country's international clinics is also stark.

At Beijing United Family Hospital and Clinics, a joint China-US venture mainly serving the capital's expatriate community, the use of antibiotics has been kept at 12 to 15 percent.

"We don't prescribe antibiotics of the common cold," said Andy Wang, a Chinese American physician at the hospital who worked in Seattle for five years before practicing in China. "We only use it when we find evidence of an increase in white blood cells."

Capping the bottle

Aware of the growing problem with antimicrobial resistance, the Ministry of Health in 2005 began constructing a monitoring network for Chinese hospitals. More than 170 first-class facilities are now included in the system, which was credited with finding the three NDM-1 superbug cases reported on the Chinese mainland last month.

Some hospitals have also taken the initiative and tightened controls on the use of antibiotics by staff.

"We carry out 500 spot checks on medicine prescriptions every month," said Xu Qian, chief physician with China-Japan Friendship Hospital's infectious diseases unit. "If any inappropriate use is found, the related doctor's bonus is downgraded."

The move has helped reduce antibiotic use from more than 70 percent to between 50 and 60 percent, said Xu, who added that "a monitoring system for the use of drugs, especially antibiotics, is now being built".

To cut down on the abuse of antibiotics in small hospitals and village clinics in Guangdong, the pharmacology association under the Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Center is organizing training programs led by experienced doctors.

However, the efforts of just a few hospitals and social organizations are far from enough to solve the problem, said Xiao Yonghong, chief physician of the No 1 Hospital affiliated to Zhejiang University.

|

|

"First of all, the government needs to draft a law on antibiotic use," he said, warning about legal loopholes. "Second, hospitals need to cut the influence producers have on doctors in choosing medicines."

Xiao, who is also a professor at the State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, explained that Chinese doctors have too many brands to choose from, especially when it comes to antibiotics, and he fears their decisions are often affected by representatives from drugs companies.

"I don't understand why the State Food and Drug Administration need to give hundreds of production licenses to the same drug," he said.

China began producing antibiotics about 60 years ago, although choice was extremely limited until the 1990s, leaving hospitals to depend on imported drugs.

Today, China is the world's largest producer of antibiotics, boasting 181 brands, according to figures released at the Chinese Summit on Antibiotics in 2009. More than 83 percent of the 147,000 tons of antibiotics made annually in China are consumed domestically.

Ironically, the antibiotics that once helped defend people against bacteria is now making it harder to kill.

"It's hard to imagine what will happen if antimicrobial resistance gets overwhelmingly high," said Xu at China-Japan Friendship Hospital. "It would be like going back to the days before antibiotics."