Society

The games of true champions

By Tang Yue (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-30 08:28

|

Large Medium Small |

Special Olympics gives intellectually disabled a fast track to glory. Tang Yue reports from Fuzhou.

|

|

Gercho Lhamo, a 10-year-old Special Olympic athlete from Tibet, celebrates after winning a 50 meter race in Fuzhou last week. [Cheng Mini / Xinhua] |

Standing on the winner's podium, Su Fang thrust his gold medal into the air and shouted: "I made it. I made it."

After finishing first in the men's 50 meter sprint, the 23-year-old appeared more excited than the average champion and continued his cheering long after he had returned to the stands.

But Su is no average champion. He has Down syndrome and the race he won was at the Fifth National Special Olympics of China in Fuzhou, capital of Fujian province, from Sept 19 to 25.

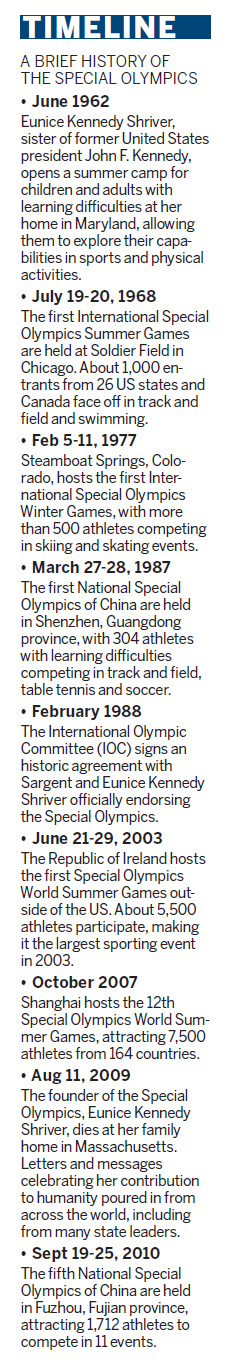

Unlike the Paralympics, which is an event for all athletes with disabilities, the Special Olympics has focused on people with intellectual disabilities since it was founded in the United States in the 1960s.

In China, the popularity of the event has soared, with entrants increasing from just a few hundred in 2000 to 1 million today, accounting for roughly one-third of all participants across the globe.

According to the event's rules, anyone who has trained for eight consecutive weeks and taken part in a competition from school to world-class level qualifies as a Special Olympic athlete.

Su first competed in 2002 and won his first world title at the 2007 World Special Olympics Summer Games in Shanghai, where he took gold in the 50 m sprint.

"It will always be the happiest moment of my life," said the runner, who hails from Dalian, Liaoning province in Northeast China. "I proved I'm the best, the best in the world. I like the feeling of winning so much. It's great."

After becoming a star Special Olympics athlete (he also won the long jump and softball throw events in Fuzhou), Su has had to get used to that winning feeling and the interviews that follow.

"It's not easy being a celebrity," he joked before excusing himself so he could send a text message to his mother, Yang Jinxu, to tell her about his victory.

"He wrote, 'Mum, your son won again. Your son didn't let you down'," Yang later told China Daily, before admitting that the victories Su enjoys today were beyond her imagination when, as a 4-year-old, he had stood in front of the family's television set and waved his handkerchief, imitating an athlete on the winner's podium.

"My husband and I burst into tears when we saw that," said the 49-year-old. "We knew our son didn't want to be a loser all his life. Like other kids, he wanted to taste victory, to be honored.

"At that moment I thought there was no chance for him to stand on that podium but now he has made it. He has won respect for himself and won a lot of pride for me."

Patience and progress

The road to glory is never an easy one, however; and for disabled people it can be twice as hard.

Coach Xu Guangsong still remembers the first time he asked the stoutly built Su to try the long jump eight years ago.

"A teenager without learning difficulties should be able to jump at least 1.5 meters but Su could only manage 10 centimeters," said the physical education teacher at Shashikou Special School in Dalian. "That's where we started - and this year he won the gold by jumping 1.57 meters.

"Mentally disabled children can't learn that fast and they can't simply copy other people's actions," he explained, "but sport makes them happy and, once they love it, they try really hard, even if it takes 1,000 times to make real progress."

That hard work usually pays off - in more ways than one. Experts say that training and competition not only improves students' physical health but also boosts self-confidence and communication skills, giving them greater independence.

"It's not that they are incapable, their abilities just need to be awakened and sport is the best tool," added Lu Yan, a professor of adopted physical activity at Beijing Sports University.

No one knows better about the difference that is made once a disabled youngster develops a passion for sport than Yang.

When Su participated in a table tennis competition in 2005 in Shenyang, Liaoning province, it was the first time he had traveled without his parents.

"To be honest, I secretly followed the team because I was afraid he wouldn't be able to take care of himself," said Yang sheepishly. "It was hard for him but I found he was learning much faster than if he was at home, from preparing his kit to communicating with players and staff."

The proud mother explained she sees how much Su has progressed after he returns from every competition.

"He used to be able to write only a few Chinese characters and they'd be full of mistakes but now he can write beautiful sentences. What's more, he's not afraid to talk to others," she said. "I didn't realize he had such potential and I don't think it would have come out without the Special Olympics."

After joining the Special Olympics movement in 1985, China staged its first national competition two years later in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, where just 304 athletes took part in three disciplines - table tennis, soccer and track and field.

A total of 1,712 sportsmen and women competed in Fuzhou this year, which featured 11 events.

To better develop the potential of athletes, this year's games also included five non-sporting events - a health program, a teenagers' summit, a family summit, a university plan and a Special Olympics research forum.

"China has made enormous progress with the Special Olympics in the past decade," said Timothy P. Shriver, chairman and CEO of Special Olympics International, which was founded by his mother, Eunice Kennedy Shriver. "The world games in Shanghai was the best ever and the event in Fuzhou was very impressive."

Despite the improvements, much more work lies ahead and he urged China to build not only its economic power but also its social power.

"The Special Olympics is not only about the games, it is about everyday life," said Shriver. "It is about everyone; not just those with learning difficulties and their families but for everyone in society to say hello, to be friendly, kind and generous."

|

|

Three teenagers compete in the roller-skating competition. [Hu Meidong / China Daily] |