Profiles

Teacher helps lepers' children

By Huang Zhiling (China Daily)

Updated: 2006-03-28 06:01

|

Large Medium Small |

YUEXI, Sichuan: On the surface, 47-year-old Wang Wenfu looks like an ordinary man.

Wang's dark skin, quiet nature and small frame, however, are merely the exterior of a courageous and compassionate man who spent 19 years teaching children of lepers in an isolated village primary school in Yuexi County, Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture in Southwest China's Sichuan Province.

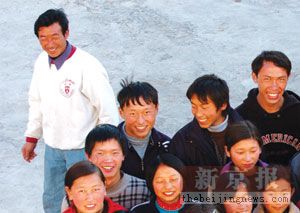

Wang Wenfu (L) together with his students [thebeijingnews] |

China Central Television (CCTV) first reported his story last year and nominated him for the list of 10 persons who touched the nation's heart in 2005.

Although Wang failed to make the final list, his nomination put leprosy in the spotlight, when before it was a disease long forgotten by most Chinese.

By 1999, 90 per cent of Chinese cities and counties had rooted out leprosy, and the nearly 400,000 lepers formerly confined to colonies had recovered and returned to mainstream society a far cry from the 1960s, when leprosy meant a deadly disease that deformed faces and limbs.

In the 1960s, the Yuexi county government moved all the county's lepers to Dayingpan Village and built a special hospital for them. As their number rose from around 50 to more than 100, the village became known locally as a lepers' colony.

Cornered village

As more lepers gave birth to children in the village, the county education and health bureaus allocated 8,000 yuan (US$996) in 1986 to set up a primary school to wipe out illiteracy among school-age children, according to Wan Yongkang, former chief of the Education Office of Yuexi's Xinmin Town, which administers Dayingpan Village.

"But no teacher on the government payroll was willing to work there," Wan recalled.

Wan found two temporary teachers for the school, but they left in less than a year.

" I was worried about finding another temporary teacher who would commit to working in the school. Wang Wenfu became a possible candidate as he was the only one willing to take the job," said Wan, who is also one of the school's founders.

At the time, Wang said he was working as a technician in an apple orchard. He also worked as a driver. "I never dreamed of becoming a teacher, let alone one in a lepers' village," Wang recalled.

Wang lived in Gaoqiao Village in Yuexi, which was half an hour's walk from Dayingpan Village. When he was 9, his mother passed away. Soon afterwards, his elder sister married and moved away, and his father lost his sight.

Wang quit school after just one year in junior high for a job that would support his family.

"As the family had only 0.2 hectares of land, we lacked grain four or five months a year," Wang said. "I took the teaching job without hesitation in hope of earning the 24 yuan (nearly US$3) monthly salary to support the family."

In September 1987, Wang arrived at the school and cringed as he stepped onto the platform and met the students' stares.

"I had not received any professional training and feared I would be unfit for the job," he said.

In the first week, Wang was also afraid to have any close contact with the students. But gradually, he became used to the environment.

The students were of the Yi ethnicity and could not understand putonghua. Wang could not understand theirs either.

So, with the help of older students, Wang began learning the Yi language and teaching in both putonghua and the Yi language.

"I wrote words in the Yi language first on the blackboard and wrote their Chinese equivalent underneath," Wang said.

But perhaps Wang's greatest challenge was trying to teach students whose ages ranged from 7 to 15. He divided the 78 students into three groups and divided the blackboard into three sections. Each section catered to one of the three age groups.

Wang encountered other problems: 78 students in a cramped house, prejudice against lepers that prohibited kids from attending local high schools and parents pulling their kids from school to do farm work.

One student after another dropped out. About 40 remained.

"To keep the rest of the students, I taught them how to sing popular songs," Wang said. "The songs attracted not only children but also adults to the school, for life was boring in the village."

The village didn't have electricity until 1992 and didn't have a television set until 1997.

Since the school lacked sports equipment, Wang got a second-hand basketball and a hoop from the Education Office in Xinmin Town. He used two pine branches to erect a basketball pole in front of the classroom and began teaching the students how to play.

"It was sports that brought us closer," he said.

For 15 years from 1987 to 2002, Wang, the temporary teacher, taught the students Chinese, mathematics, music and sports. He was both the teacher and headmaster, though his commitment to the students cost him friendships.

"I felt lonely after students left the school," Wang said. "But prejudice was more dreadful than loneliness."

Whenever he returned from the school to his home village of Gaoqiao, villagers would talk behind his back and suggest that he was infected with leprosy because he taught students in the lepers' village. Some even refused to sit in chairs he had touched.

"I felt very sad, but it was the genuine smile of my students that comforted me and kept me teaching," Wang said.

However, a 1989 incident almost forced him to leave.

His daughter was hospitalized after being scalded in an accident. To Wang's monthly salary of 24 yuan, his daughter's 1,200 yuan (US$149) hospitalization fee was "an astronomical sum."

Struggling to repay the debt incurred from his daughter's hospitalization, Wang planned to quit and find a better paying job. In 1999, the town raised his monthly salary from 24 yuan to 56.5 yuan (US$7). Still, it was far from enough.

"The wages were meagre, for I had three children to support," Wang said.

In the winter of 1999, a friend found him a welding job in Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan. But at the last minute, Wang changed his mind.

"Whenever I was busy in the school, some students and their parents would help my family dig the fields and plant crops," Wang said. "They were so kind and I didn't want to give them up."

Hope comes

Since 2000, the Wings of Hope, a non-profit organization from Taiwan Province, has invested 3 million yuan (US$373,599) to build a new three-storey school building, dining hall, toilets and a road leading to the school.

Thanks to the improvements, 11 teachers have worked in the school since 2002. Eight are still there.

The school has 167 students, ranging from the first to sixth grade. Last June, 14 students graduated and entered the Xinmin Town High School and became the village school's first graduates.

Previously, prejudice had kept Dayingpan Village students from attending the area's high schools.

"Thanks to the efforts made by the local government, high schools outside the village started enrolling its graduates last year," Wang said.

In the final examination before this year's winter vacation, the average score of the school's sixth graders ranked first among over 20 schools in Xinmin Town.

"The achievement has changed people's prejudice against children of lepers, and their children are more confident of their future," said Luo Guiping, the village school's incumbent headmaster.

One of these children Ji Piyao, a 15-year-old sixth grader wrote in a composition that he hoped to use knowledge to change his destiny and give his home village a major face-lift. An accompanying painting also by Ji displayed neatly arranged houses, lush crops and flocks of oxen and sheep.

"I feel that my life is meaningful, for I have seen students become literate, do arithmetic and find hope," Wang said.

Wang has also been rewarded with a pay increase.

Last year, the government added Wang to its payroll and his monthly wages rose to 1,123 yuan (US$140).

(China Daily 03/28/2006 page14)