Opinion

Troubled IMF needs changes

By Martin Khor (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-05-25 13:09

|

Large Medium Small |

The arrest of Dominique Strauss-Kahn on charges of sexual assault was followed by his resignation as managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This has sparked a race for his successor, one of the world's top two finance posts.

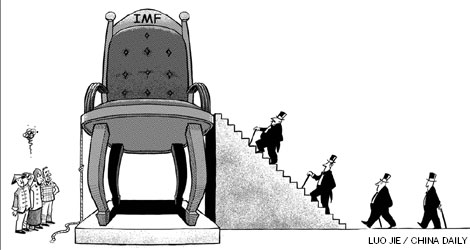

European leaders were quick off the mark, arguing that a European should occupy the post again according to the old but discredited tradition. It has been increasingly recognized that the convention of a European IMF managing director and an American World Bank president can no longer be justified.

People for the two posts should be selected from any country according to merit, not on the basis of being Europeans or Americans, which is a colonial or neo-colonial principle.

Candidates from developing countries should have an equal chance, especially since the countries have increased their share of global gross national product, and many of them (especially China and other Asian nations) have large foreign reserves.

The international media have mentioned well-known figures from India, South Africa, Singapore and Turkey who could succeed Strauss-Kahn. But the European Commission president and political leaders of Germany, France, Italy and other European countries insist on another European, giving reasons such as Europeans are the biggest creditors, are facing a serious crisis and have candidates of merit.

| ||||

European leaders are arguing that the IMF chief needs to be a European because much of the present IMF loans in value are going to European countries such as Greece, Ireland and Portugal, and Europe is facing a serious financial crisis. They argue that a European IMF chief would be best suited to deal with the European crisis because he/she should or would understand the region better.

This is a strange argument, fraught with double standard. When East Asian countries suffered a debt crisis from 1997 to 1999 and the IMF's main clients became Thailand, Indonesia and South Korea, no one argued that the IMF should be led by an Asian because he/she could understand the region's problems more deeply.

Similarly, there was no chance of an African or South American occupying the higher posts of the IMF even when many countries in those regions faced financial crises and were the main borrowers in the 1980s and 1990s.

Veteran journalist and analyst of international organizations and affairs Chakravarthi Raghavan argues that the spreading economic crisis in Europe is indeed a valid reason for a non-European to head the IMF.

In the 1980s, when democratization of international institutions was on the agenda, the United States and Europe argued that since the developing countries are borrowers, they cannot be allowed to control the IMF or World Bank, Raghavan told the IPS press agency. "This logic applies here. No European should be allowed to head the IMF" now, he said. The IMF's rescue packages for Europe have become efforts to protect the interests of French and German banks which are major creditors and bond holders of Greece, Portugal and Spain.

The outrageous demand by Europe that it must continue to monopolize the IMF's top post is a clear case of double standard, especially when Western countries are trying to "teach the principles of democracy and meritocracy" to developing countries.

Despite this, Europe is likely to succeed because of the undemocratic decision-making system in the IMF, as is the case in the World Bank, where European countries hold more than 30 percent of the votes, the US 16.7 percent, Japan 6 percent and Canada 3 percent. If developed countries unite under a single candidate, they will get their way.

Still, it will not be a guaranteed or even an easy win for Europe. One reason is that public opinion (including that of Western civil society) finds European monopoly indefensible and outrageous in the modern world. A group of NGOs have called for a fair, transparent and merit-based process for selecting the next IMF chief.

Many developing countries recently called for an open and democratic selection process for the heads of the IMF and World Bank. Developing and emerging countries together control 44.7 percent of the votes, and the IMF chief must get 85 percent of the votes.

At a meeting in April, ministers of the G24 (a group of developing countries that operate in the IMF and World Bank) repeated their call "for an open, transparent, merit-based process for the selection of the president of the World Bank and the managing director of the IMF, without regard to nationality". They also called for "concrete actions and proposals to be put forward to guarantee this change".

While the developed countries have a majority of the voting rights, the developing countries can theoretically block the candidate put up by Europe or other developed countries.

The reality is that the developed countries tend to unite behind a candidate from among them, while developing countries have not been able to come up with a single candidate of their own who they could support en bloc.

Though the selection of a new IMF managing director is of immediate importance, more important is the reform needed in the IMF's policies and operations.

A South Centre paper, authored by chief economist Yilmaz Akyuz, points to its failure in preventing financial crises, which is its main task. The change of IMF's leadership is a good opportunity to discuss the weaknesses of the IMF and to reform its policies.

The author is executive director of the South Centre, a think tank of developing countries, based in Geneva.

| 分享按钮 |