Appreciating the distinction between work and labor

I'm standing among rows of kale in a greenhouse in Gaomi county, Shandong province, with a camera pointed at me, its lens vacant and black. My performance is captured and stored, where it will lie dormant in digital form until it is someday edited. Around me, women pick green and purple leaves from stalks and store them in mesh sacks hanging from their hips or strapped to their backs. The air is sticky with the smell of damp dirt and sweat. I am working, but they are laboring.

Work and labor: this is an important distinction for me. Hannah Arendt contrasts the two in her lecture, "Labor, Work, Action". She labels work as that which fabricates the world we live in, which produces something that exists beyond its use. It's an effort toward immortality. Conversely, labor is attached to the cycle of biological life; it must be repeated, often as soon as it is finished.

The idea that my video might live beyond me is seductive. After all, I work for an international publication. I have planned this shoot for weeks and devised a script that speaks about the push and pull between tradition and modernity. My narrative illustrates the value of a connection to the land. My ideas are big; I feel important.

These are illusions. I have never plucked a vegetable from the ground.

I ask the women to show me how it is done — identify a healthy leaf and trace its stem back to the stalk; apply leverage at the base until it snaps off. They assure me that the leaf is pesticide-free and urge me to taste the leaf I've just picked. It is crisp and watery, with a ghost of sweetness that haunts the tongue.

I think about my relationship with food. By the time it reaches my mouth, it has passed through an unknown number of hands, traveled across biomes to be cleaned and processed, packed, cooked, and spiced. I chew the leaf and marvel at the women efficiently packing their sacks.

In some cases, I am told, these laborers can trace their family tree back to this land for dozens of generations. The farm relies on their agricultural knowledge, which I suspect is akin to intuition for them. It's a concept that I struggle to comprehend. The job of the farmers in the greenhouse is to sustain metabolism. They are the inheritors of a labor that exists as a function of time itself. My job is to project an abstraction. I'm suddenly uncertain that the potential longevity of my work holds up against permanence.

How might I tell their story in a way that inspires empathy? I can describe their conditions and efforts, and my descriptions can achieve a passable level of plausibility if I spend the day with them and practice their deeds. Ultimately, I will fall short of knowing them, and so too will my audience.

And yet, I am a product of their labor. I am only able to take my relationship with food for granted because they work until their backs ache, and their fingernails are packed with dirt. If I can't identify with them, perhaps appreciation will do for now.

Today's Top News

- Confidence, resolve mark China's New Year outlook: China Daily editorial

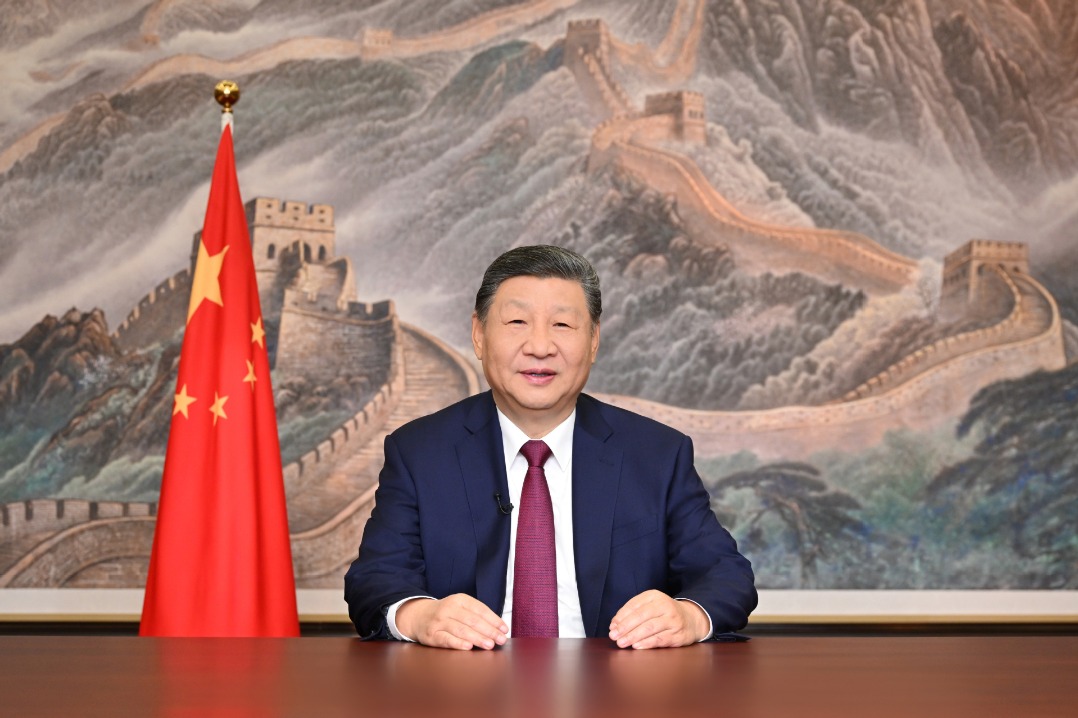

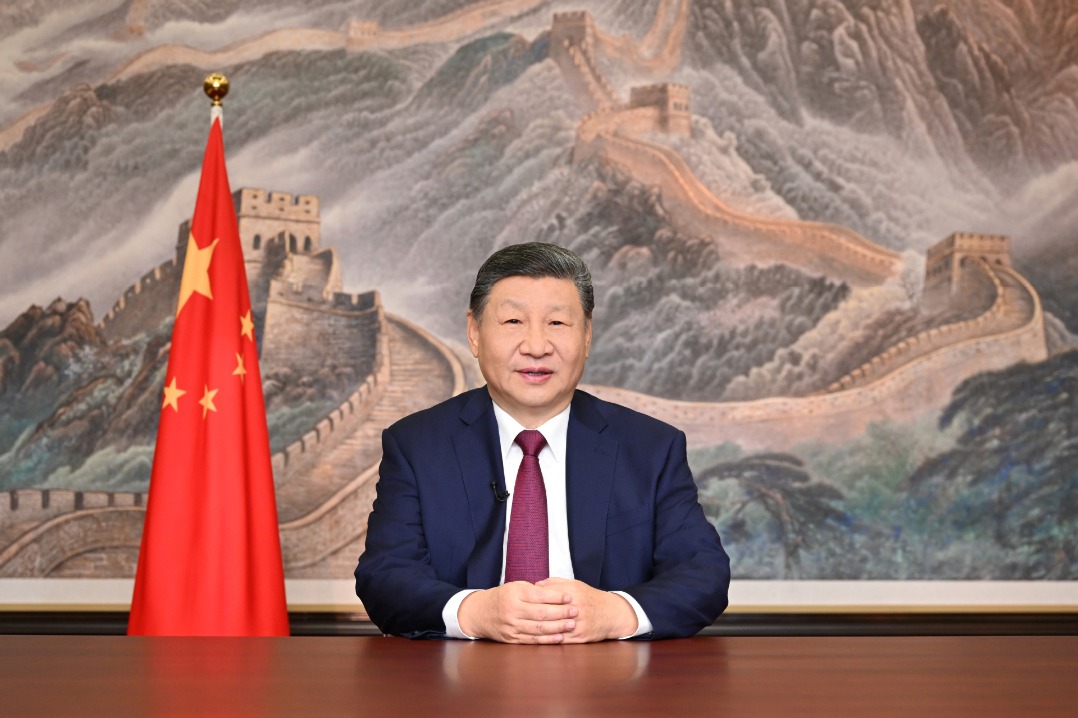

- Key quotes from President Xi's 2026 New Year Address

- Full text: Chinese President Xi Jinping's 2026 New Year message

- Poll findings indicate Taiwan people's 'strong dissatisfaction' with DPP authorities

- Xi emphasizes strong start for 15th Five-Year Plan period

- PLA drills a stern warning to 'Taiwan independence' separatist forces, external interference: spokesperson