Practical platform for progress

Beijing+30 will be judged on the results it delivers in measurably improving gender equality

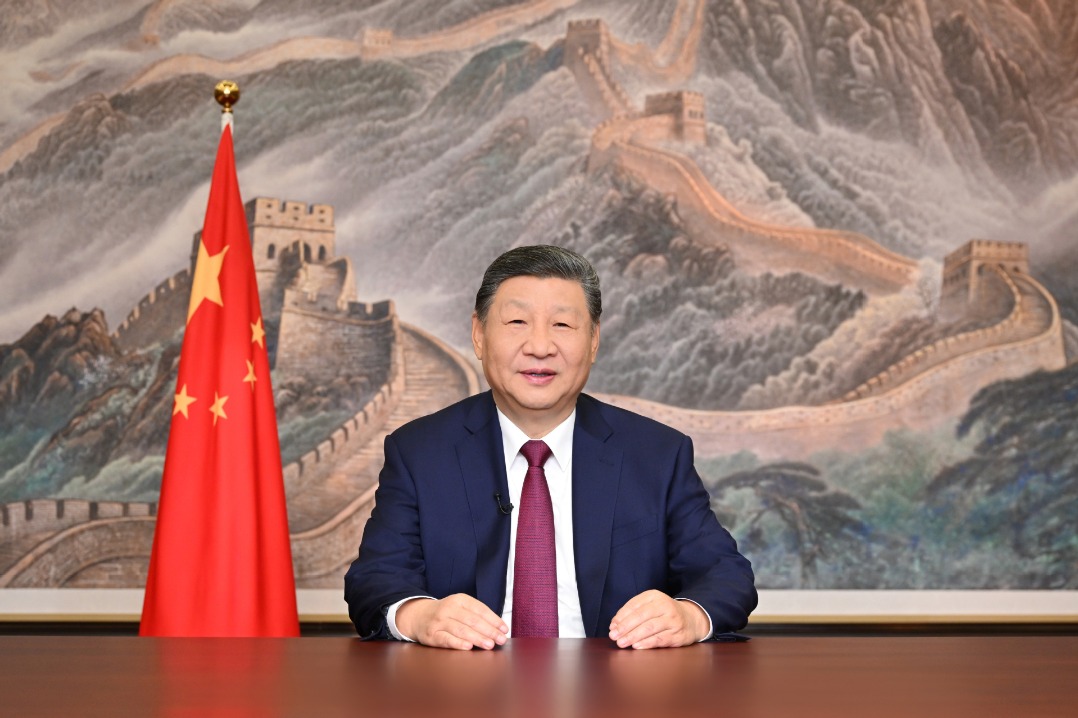

This year offers a special vantage point for examining the progress and development of the cause of women's equality. The Beijing+30 Action Agenda, a United Nations initiative led by the UN Women, is a momentous reaffirmation of the central importance of achieving gender equality as critical to development, peace and security, 30 years after the landmark Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. As the Global Leaders' Meeting on Women convened in Beijing on Oct 13, China's focus on women's development is more than a commemoration. It signals a practical commitment to embed gender equality in public policy and daily life, with the scope to deliver at home and internationally. It also invites clear-eyed stocktaking: where progress is real, where gaps persist, and which practical steps can turn ambition into delivery.

China's modernization has widened the space for women to thrive. Economic growth and social change have strengthened women's standing at work and in everyday life.

Since China's reform and opening-up in 1978, rural women have gained land-contracting rights on a par with men. Hundreds of millions have moved from villages to cities, benefiting from industrialization and urban services. Education has expanded quickly. As development has advanced and rural-urban gaps have narrowed, the old norm of "men first in schooling" has largely faded. Net enrolment for primary-school-age girls stands at more than 99.9 percent, and women now make up more than half of higher-education students. Equal access to education has helped women build human capital and competitiveness, laying a firm foundation for fair employment and social recognition. Social protection now has broad reach across town and country, with basic pension and basic medical insurance systems providing near-universal coverage, and more than 111 million women are enrolled in maternity insurance. This institutional base is a platform for the next round of reforms. Female entrepreneurship is on the rise, and social attitudes continue to shift as more women choose self-development, self-expression and civic engagement.

Taken together, these gains show that Chinese-style modernization has delivered not only prosperity but also substantive advances in gender equality and women's development. Spotlighting women's development at the Beijing+30 milestone signals China's resolve to go further and to deepen international exchange and cooperation.

The job, however, is far from done. Biological differences, entrenched role expectations and unequal care burdens still leave many women at a relative disadvantage. With only five years to 2030, several gender-related targets are off track and global progress has slipped. The UN Women estimates suggest that in the world, over 600 million women and girls live under the threat of deadly conflict; an alarming 2 billion lack any form of social protection; and around one in 10 women live in extreme poverty. Violence, discrimination and economic inequality persist, while the digital gender divide is shaping women's health, education and economic prospects in profound ways. Progress is uneven across regions and cohorts, and risks now straddle both offline and online spaces — another reason why systems must be more anticipatory and better tailored to context.

China's record shows both advances and shortfalls. The gaps largely reflect the structural frictions that emerge as society urbanizes, ages and digitizes, which in turn calls for system-wide solutions rather than piecemeal fixes. Government action is underway, and several indicators are improving step by step.

In education, test-driven competition — neijuan — adds pressure on young people, including girls, harming their well-being and sound life planning.

In the labor market, gender bias has not disappeared. Some jobs still exclude women; the motherhood penalty — challenges women face in workplace after having children — and other hidden costs persist; and equal pay remains a challenge with lower wages for women in several sectors.

In public health, policies that promote women's well-being need strengthening. Screening for cervical and breast cancers is part of the national basic public-health package, but the implementation remains uneven in many central-western and rural areas.

In social security, statutory retirement ages push many women out of work earlier, depressing pensions and widening gender pension gaps; basic medical insurance does not yet fully shield families from the costs of serious illness, and women face higher risks overall; and maternity insurance still centers on formal employment, leaving many flexible workers and rural women uncovered.

In services and rights, targeted welfare and services for women remain scarce. In some rural areas, women who have married out see their land-contracting rights weakened.

In public life, women remain underrepresented. In the current National People's Congress and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference National Committee, they hold under one-third of seats — short of the balanced goal.

None of this negates the progress to date; it just sharpens the priorities for the next phase of reform. Turning pledges into delivery calls for two complementary lenses — equality and reason.

An equality lens uses institutions to repair structural gaps. For example, exploring "maternity pension credits" (as in Germany), so childbearing and care periods count as deemed contributions and do not depress pensions; introducing "use-it-or-lose-it" paternity leave — a Nordic-style father's quota — to share care fairly and reduce gendered hiring bias; securing rural women's land-contracting rights after marriage and migration through reliable registration and orderly land transfers; strengthening the enforcement of the anti-discrimination law, banning pregnancy-related bias and moving toward pay-gap transparency; gradually extending employment-linked maternity insurance into a universal birth-related protection scheme so flexible workers and rural women are covered; and ensuring a full and effective rollout of cervical and breast cancer screening in rural and less-developed regions.

Equally important is investment in affordable childcare and long-term care services that ease unpaid care burdens and increase women's labor-force participation. Strengthening women's pathways into science, technology, engineering and mathematics sectors and closing digital and skills gaps will widen opportunity as technology reshapes work. In political life, appropriate measures should be explored to secure women's voices in decision-making.

A reasoned lens then makes changes stick through priorities, certainty and partnership. Policy should focus on women's aspirations for a better life by building comprehensive, life-course-oriented public services and social security, while sequencing reforms sensibly within real resource and institutional constraints.

At the same time, it should tackle urgent problems that women face today and offer clear and stable expectations for the longer term — by improving laws, policies and delivery systems, and by building rules-based institutions with digital and other technological support that are sustainable, predictable and measurable.

It should also adopt a partnership model in which government, business and civil society share the load. For example, companies can use digital tools to support public-health and social-service roll-outs, nongovernmental organizations can provide specialist services in employment, health and mental well-being, and universities and vocational institutes can co-design curricula and re-entry pathways with employers.

It should also align central and local finance, and — where appropriate — leverage public-private partnerships and social investment to expand provision.

A reasoned lens also means guarding against extremes. It keeps advocacy for gender equality from sliding into gender antagonism, prioritizes constructive remedies to structural inequities, and helps ensure that women share more fairly in the gains of development and technological progress.

What will define Beijing+30 is not rhetoric, but whether an equality-plus-reason agenda extends to every key stage of women's lives, prioritizes the most urgent needs, and delivers results that can be measured and reviewed.

The author is an associate researcher at the Institute of Population and Labor Economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.