A society that fostered symbolism and wealth

From the late Warring States Period (475-221 BC) to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24), along the shores of Dianchi Lake in Kunming of Yunnan province, there existed an ancient civilization known as Dian.

Although archaeologists have yet to uncover any written language from this civilization, a large quantity of uniquely shaped bronze ware unearthed in the last century serves as a vivid historical record of the ancient civilization, bringing to life the story of this regional state that once thrived more than 2,000 years ago on the southwestern frontier of China.

Unearthed in the 1950s from Shizhaishan and Lijiashan sites in Kunming, Yunnan province, a treasure trove of ancient Dian currency (cowrie shells) and over 10,000 bronze ware were discovered. Among them stands out a unique type of bronze artifacts: bronze cowrie containers with decorative covers featuring vivid miniature sculptures.

In the ancient Dian Kingdom, which was far from the sea, cowrie shells were rare and became a kind of currency as valuable as gold and silver. The nobles thus created special bronze containers to store these shells, much like today's piggy banks.

However, for the Dian people, the cowrie container was much more than a mere storage vessel: It was a symbol of wealth, power, and status, and played a crucial role in ancestral rituals.

"These bronze artifacts are unique to the ancient Dian people, never found in other regions, and is regarded as the representative artifact of the Dian bronze civilization," says Fan Haitao, deputy director of the Yunnan Provincial Museum in Kunming, where lots of these cowrie containers are housed and exhibited.

"While bronze ware from the Central Plains region mostly features symbolic and abstract patterns, the style of Dian bronze artifacts is more realistic and closely related to everyday life", says Fan.

The bronze lids of the cowrie containers, for instance, were adorned with tiny figures and structures, showcasing scenes from the daily lives of the Dian people, such as hunting, farming, and weaving. They also captured the Dian people's leisure activities, including bullfighting, dancing and making music.

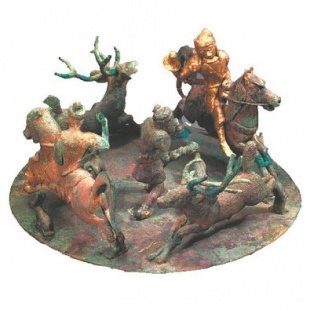

In the collection of the Yunnan Provincial Museum lies a fascinating bronze cowrie container from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24), crafted by skillfully welding two bronze drums together. Its lid vividly captures a hunting scene: three figures, each armed with a long sword. Two of them are mounted on horseback, in hot pursuit of a fleeing deer, with one rider entirely gilded. The third figure stands at the center of the lid, poised to hunt another deer, flanked by two dogs ready to pounce on their prey.

The bronze lid resembles a miniature society, intricately carved with a multitude of human and animal figures. The most populated of these cowrie containers, now housed in the National Museum of China in Beijing, boasts an impressive 32-centimeter diameter lid adorned with 129 figures. It also features stilted buildings, bronze drums, columns, cauldrons and various animals, making it the most complex piece among the bronze artifacts of the Dian Kingdom.

This elaborate creation captures a widely practiced sacrificial ritual among the ancient southwestern tribes. The sacrificial plaza depicted on the bronze lid also doubles as a bustling marketplace, reflecting the vibrant trade exchanges that the Dian Kingdom maintained with neighboring states and regions.

Animals are a focal point in the intricate carvings of Dian bronze ware, such as oxen, tigers, deer, monkeys, rabbits and birds. These creatures are depicted either alone, in groups, or interacting with humans, all rendered in unique and lifelike forms. Among these, oxen are the most frequently represented.

During the agrarian civilization era, the people of Dian did not use oxen for farming, says Fan. Over 2,000 years ago, they held oxen in high reverence, using them solely for sacrificial offerings. The Dian people were also among the earliest in the world to engage in bullfighting and related activities. A bronze buckle ornament collected by Fan's museum vividly depicts a scene of an intense bullfighting event.

Due to the scarce historical written records about the ancient Dian Kingdom, there have been doubts about whether this regional state inhabited by indigenous people truly existed, says Jiang Zhilong, a researcher at the Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology.

In 1956, the unearthing of a large number of bronze artifacts, including these uniquely-shaped cowrie containers, unveiled the mysteries of this ancient kingdom that had been dormant for over 2,000 years. Recently, discoveries of Jiang's team of a significant amount of clay seals and wooden slips at the Hebosuo site in Kunming have further provided textual evidence confirming the existence and demise of the ancient Dian Kingdom.

"We still need to spend years conducting further research on the ancient Dian Kingdom," says Jiang.