An eccentric approach

Met exhibition shows how famed Chinese artists used depictions of the natural world to comment on society, Zhao Xu reports in New York.

In 1753, 60-year-old Zheng Xie (Zheng Banqiao) left behind his life as a county magistrate once and for all, to engage solely with painting and poetry, and a close-knit circle of like-minded friends known today as the "eight eccentrics of Yangzhou".

Yangzhou was an affluent eastern Chinese city and haven to scholars, painters and calligraphers, disenchanted or not.

The decision was voluntarily and involuntarily taken: voluntarily because Zheng had helped to seal his own fate as a court official by openly disobeying his superior; involuntarily because Zheng, who had spent the first 43 years of his life trying to pass the examinations needed to enter imperial officialdom, was left with no choice — to concur with his superior would mean to close the county granary to starving villagers at a time of great famine.

Zheng, who once wrote that "the rustling of the bamboo leaves outside my abode reminds me of the grunting and groaning of the destitute and the downtrodden", chose to listen to that sound, one that resonated deeply with him. Before departing, he painted a few stems of "skinny" bamboo "for use as fishing poles over wind-ruffled water", according to his own inscription.

If anything, the bamboo rustling proved to Zheng that integrity was vital.

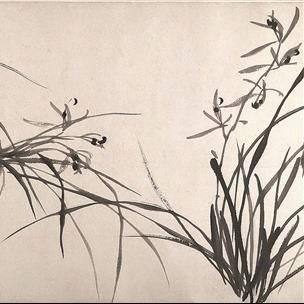

This belief is evident in many of his works, including one recently on display at an exhibition, titled Noble Virtues: Nature as Symbol in Chinese Art, at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In his own inscription, the painter-calligrapher described his work as a "portrait" for a friend who, like the bamboo, harbored the same "hollowed heart", one that's unclogged by worldly pursuits. One cannot help but think that the 49-year-old Zheng was also creating his self-portrait, at a time when many of the trials and tribulations of his life lay ahead.

"When the painting was done in 1742, Zheng was in Beijing, capital of the Qing empire (1644-1911), socializing with members of an elite, literary class, many of whom were scholar-officials," says Joseph Scheier-Dolberg, the show's curator.

Complete disillusionment would not come until a decade later, but the man had already matured as an artist. With his "economical, almost strategic" application of ink — to quote Dolberg, Zheng conjured up orchid flowers complete with pistils and stamens, with just a few strokes and dabs. The orchids' slender leaves echo the spindly stalks of the bamboo, and both find company in rocks, a symbol of constancy in the artistic language of ancient China.

While Zheng's work exudes tranquillity, elsewhere the bamboos are subjected to wind and rain, with wispy tendrils swept up or leaves soaked and heavy.