Two's company

When the Hong Kong Philharmonic and Hong Kong Ballet staged a historic coproduction, they took collaboration to a new level. Madeleine Fitzpatrick has a ringside view.

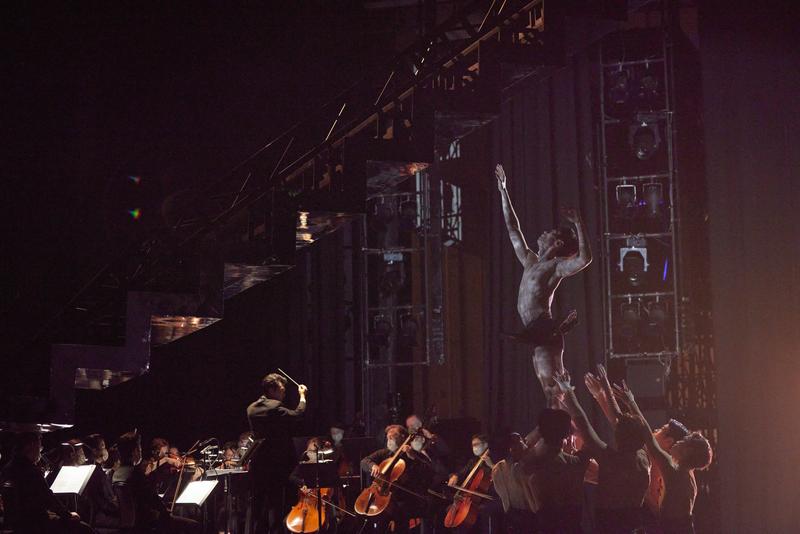

The first-ever coproduction of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra (HK Phil) and Hong Kong Ballet (HKB), Carmina Burana, which ran Oct 14-16, comprised two strikingly contrasting halves. Audiences were treated to a chamber orchestra on stage in the first half - the world premiere of The Last Song. The second half was the Asian premiere of the title piece, Carmina Burana (Songs of Beuren).

It's very unusual to have an orchestra on stage for a ballet, confirms Lio Kuokman, HK Phil's resident conductor, whose friends call him by his surname, Lio. "Our musicians aren't just accompanying - we're integrated into the dance," he adds.

For the dancers, too, it was a special experience. "When the orchestra's in the pit, what the dancers hear are the onstage monitors," says Septime Webre, HKB's artistic director, who choreographed Carmina. "With the orchestra on stage, the dancers are experiencing what the audience experiences in a concert hall, where the music's coming right at them. It's thrilling."

While HK Phil and HKB have been performing together since the 1980s, the milestone coproduction is the first time they were given equal billing, the companies having a joint say over the creative process.

Hauntingly emotive, The Last Song was created by Ricky Hu, HKB's choreographer-in-residence. "Lio really helped me because originally I'd chosen different music," says Hu, who'd already spent a month listening to Bach's oeuvre before he shared his vision for the show with Lio. The conductor suggested two pieces so touching and emotional, the choreographer was inspired. Hu had grown up with Oscar Wilde's fairy tales. With the seven-piece selection for Song in hand, an idea hit him: Wilde's The Nightingale and the Rose was a perfect fit.

In the work, male dancers portray Wilde and the nightingale, the latter bare-chested and in a tutu. Hu explains that the nightingale is Wilde's inner or fantasy self. The tutu seems a racy addition in an intimate man-on-man dance inspired by the most famous of gay writers, but Hu's motivation proves innocent: "Why did I choose a tutu for the nightingale? First, he's not human - no man would wear a tutu. Second, (the tutu standing for a tail feather) because he represents the bird."

Endless possibilities

Tisa Ho, outgoing executive director of the Hoqqng Kong Arts Festival, has overseen innumerable cross-disciplinary collaborations in her 16 and a half years on the job. "Collaborations between institutions can be particularly fruitful not only in increasing the resources available to a project, but also because of the possibilities of learning different ways of working, exploring new approaches to finding solutions, and of course building connections," she notes.

"Institutions that collaborate can produce something that's more impactful, so the art packs a bigger wallop," says Webre. "(The coproduction) allows us to share resources, so we're more efficient financially. It's also fun for us - there's something intrinsically good about working with your neighbors."

Webre's Carmina Burana is set to the eponymous 1936 cantata by Carl Orff, based on a manuscript of 254 poems and songs written by monks between the 11th and 13th centuries. The cantata is bookended by O Fortuna, a piece instantly recognizable, having been featured in movies and TV commercials over the years. The song's lyrics, in Latin, lament the fickle vicissitudes of fate.

The curtains rise on a somber scene of 130 singers playing cowled monks, framed by scaffolding that evokes monastic cloisters. Three world-class soloists - soprano, tenor and baritone - do phenomenally with a notoriously tricky score. The dancers wear a modified version of clerical vestments, sliced so that they swirl. Descending from the ceiling, a ballerina stands within a ring, arms outstretched in reference to da Vinci's iconic Vitruvian Man.

O Fortuna takes up where Song's poignant final scene left off. "One seems to follow the other in tone," says Webre - after which, "I go into much lighter zones." As a whole, Carmina is a feast for the eyes in perpetual motion: an extravaganza from a more-is-more choreographer, with lavish costumery by Cirque du Soleil alumna Liz Vandal. The musical styles of the two halves could hardly be more different, Lio having elected to contrast pure, intimate Bachian strings against the intensity of Orff.

A professed formalist ("not an expressionist") in his youth, Webre says it was challenging to find his way into Orff's work. Virginia Woolf's 1928 novel, Orlando, provided the key: "Something that happens in Orlando is the piece changes over time - you catapult through time." Webre's Carmina begins in the medieval period of the original texts, concluding - with the reprise of O Fortuna and the Vitruvian ballerina - in contemporary times. Along the way, costumes move through the Elizabethan, Baroque and Victorian periods as well as the Roaring '20s.

The song cycle, for Webre, represents life's journey: "You're the same at the beginning and at the end, but you're not the same at all because you had a whole journey in between. When you're born and when you die, your fingerprints are the same. But you're totally different."

Flow states

If Webre's challenge was to create a ballet based on Orff's masterpiece, Hu's lay in choreographing a brand-new work - after receiving his conductor's insightful suggestions - in 16 days flat. ("I almost died," Hu grins.)

Lio faced his own challenges when it came to both works, and he gives the impression of relishing every moment. "Ballet conducting is almost like another field because I have to understand the steps, understand the dancers' movements. Normally my scores won't say things like, 'Look at her legs! Her legs will turn three times, then you start the downbeat.'"

"The artistic collaboration could be found in Lio's intense study of the choreography," affirms Webre. "He was practically embedded on stage with the dancers. Honestly, I think he could have danced almost any role by the end."

Then there was the coordination - the need for the conductor to give the musicians lightning-quick signals in response to the dancers. "With opera, the orchestra's in the pit, but they can hear the singers. They know what's going on; they can feel it," Lio notes. "But playing for a ballet, they have absolutely no idea how fast or slow the movements are going. So the company has to rely on what I'm giving them."

He compares the job to swimming, miming breaststroke breathing: "I go up, and I see the people dancing and the chorus, and then I go down and see the orchestra."

Collaborations bring plenty of opportunities for inspiration, innovation and surprise. "Funnily enough, when I first talked to Ricky and Lio, I said, 'The music of Bach - you could make a tutu ballet!'" recalls Webre wryly. "Then I saw the costumes and I was like, 'Oh, Ricky You did make a tutu ballet.'"

- Intl research team develops damage-free etching technique for optoelectronic semiconductors

- Task force to investigate prenatal exam failure in Hubei

- Report on tailings dam collapse in Yunnan suggests accountability for 26 individuals

- Beijing-Zhangjiakou trains expand ski gear service

- Documentary 'Through Ice and Snow' is to be broadcast internationally

- China launches new remote-sensing satellite