Following trailblazer's path

Station by the Great Wall is a witness to birth and glory of China's railway. Luo Wangshu reports.

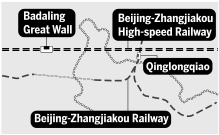

It was 113 years ago that the Great Wall in the rugged mountains northwest of Beijing was first pierced by a railway linking Beijing and Zhangjiakou in Hebei province.

Just under that "cut" lies Qinglongqiao railway station, which has witnessed the development of rail in China. Yang Cunxin, who was born and raised next to the station and later worked there, feels an obligation to tell the story of its connection to China's history.

"This was the start of railways and modern technology in China," he said, adding that railway workers should make a pilgrimage to Qinglongqiao to get to know the first chapter of that story.

Yang was born in an apartment next to the station in 1962. The residence was dedicated to station workers and their families, and Yang's father, Yang Baohua, had been a switch operator there since 1951.

When his father retired in 1981, Yang Cunxin took over as switch operator before becoming station head in 1991, a position he held until he retired in September.

Qinglongqiao station was just one of the stations built along the 200-kilometer Beijing-Zhangjiakou line, which opened in 1909. It was the first line designed and built without foreign assistance. Its chief designer, Zhan Tianyou, who was then known as Jeme Tien-Yow, was also responsible for its construction. Zhan is known as the "Father of China's Railways" for his contributions, and he and his wife are buried at the station.

Connection to the master

"I feel I have a connection to Zhan Gong," Yang said, referring to Zhan Tianyou. "I was born in 1962 and he was born in 1861, 101 years earlier. I was born and raised next to the railway he designed and built, and the year I began working there in 1981, his tomb was relocated next to it. For the 40 years I worked in the station, he was always with me."

The use of "Gong" when referring to someone is a respectful form of address in Chinese.

Yang admires Zhan so much that he has memorized the railway pioneer's writings.

His favorite is an article titled To Young Engineers. Yang took it as his motto and used it to guide his work. He even hung an excerpt in the station's exhibition room.

"Zhan Gong is more than an engineer, he is also a philosopher and a master of literature," Yang said. "Zhan is my master."

Yang's reverence for Zhan and his understanding of the railway accumulated during his 40 years on the job.

Qinglongqiao is not a big station. It has a track, a terminal that Yang has turned into a small exhibition room, a statue of Zhan, a small exhibition outside of old railway signs, the tombs of Zhan and his wife, and a famous willow tree that has been there for over 85 years. The station's sign still reads "Chinglungchiao", retaining its old transliteration from when the station was built. A thorough tour doesn't take more than 10 minutes.

This history aside, Yang admitted that doing the same work for decades was sometimes a bit boring, but said that he felt a great deal of responsibility.

"Every day on duty, safety was like a sword hanging over my head. It was like walking on thin ice my whole life," he said, adding that the first thing he did each morning was to get the weather report.

"When it was rainy, I worried. When it was snowy, I worried. When it was windy, I also worried. I never slept soundly."

Because of its location by the Great Wall and the mountains, he was always concerned that bad weather might destroy the railroad and interfere with operations.

"After taking over from my father, if I came home later than usual, his first question was usually: 'Was everything safe today?' That used to annoy me and I would tell him to stop asking. But now that my father is gone and I have a son, I sometimes wonder if my son took over from me, whether I might worry and ask him the same question. Safety is always the top priority, and my father always told me to be safe when I left home for work."

From old to new

A century ago, when trains arrived at Qinglongqiao, the operator got down from the cabin, walked to the end of the train, hopped back on and drove the train from the other end. Qinglongqiao lies at the end of a zigzag section of the line, which Zhan designed to deal with the steep gradient.

"With the limited budget and technology, it was the best choice at the time, showing Zhan Gong's wisdom," Yang said.

Other countries were skeptical, doubting the line could be completed only by Chinese because the country was weak. Its successful construction boosted national morale.

These days, even much more difficult issues wouldn't be a problem. China has the largest high-speed railway network in the world, stretching more than 40,000 km, and it crosses deserts and humid coastal areas.

Three years ago, a hundred years after the opening of the Beijing-Zhangjiakou line, a high-speed railway opened between the two cities. It was the main line of transport during the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

According to the China State Railway Group, the company that oversees all of the country's railway projects, the 174-km Beijing-Zhangjiakou High-Speed Railway, which can reach speeds of 350 km per hour, is China's first "intelligent" high-speed line, and leads the world in railway technology. The lines, old and new, are witnesses to the development of the railway network and the improvement in the country's capabilities.

Yang remembers young engineers surveying the station during the construction of the new high-speed line, but during the three years that it took, Qinglongqiao continued to operate as usual.

The new high-speed line's Badaling Tunnel now lies under Qinglongqiao.

"A bullet train can pass 3.8 meters beneath me and I don't feel the vibrations," Yang said, pointing to where the old and new line cross. For him, this is proof of China's skill at building railways.

From busy to quiet

In Yang's memories, his father was always busy at work. At its peak, the line was the most important rail corridor from Beijing to Northwest China, and the station handled 64 trains a day.

In the 1990s, international trains between Beijing, Ulaanbaatar and Moscow would stop at the station.

As new lines were built, trains diminished and so did the station.

In 2008, it stopped passenger services, and some of the trains from Beijing to Zhangjiakou and elsewhere also began to pass through without stopping.

In 2018, long-distance trains also stopped passing through the station. Since then, it has only handled one of Beijing's suburban train services, the S2 route, which mainly takes tourists to the Badaling section of the Great Wall, and commuters between downtown Beijing and suburban Yanqing.

In the spring, the suburban train passes through mountains and along the Great Wall as blossoms line the old route. When it stops at Qinglongqiao, the driver gets down from the cabin, walks to the other end and continues, just like his peers did 113 years ago.

These days, the station handles four to eight trains a day during off-peak times.

"Although the station is quieter now, it is still a living museum," Yang said.

Carrying on history

Sept 15 was Yang's last day as station head. He bought a bouquet to lay on Zhan's tomb as tribute and then climbed a hill to a rugged section of the Great Wall to take a last look at the station.

"I won't be back here often," he said, taking photos of a train entering and leaving the station.

"When one of the trains blew its whistle, I knew it was time to go home when I was a boy," he said.

He now plans to tell the story of the Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway and of Qinglongqiao and said that although China is now known for the rapid development of its railways, people should not forget where it all began.

"It all started with Zhan Gong," he said.