'Ambassadors' on a mission

Virtual influencer marketing has become the norm for world renowned brands as it's cheaper and more flexible than real-life celebrities. Wang Yuke reports from Hong Kong.

There is a new crop of influencers gaining traction on social media. They look exactly like humans and may appear to be too uncannily perfect. They might elicit a speck of unease and fuss among viewers in the "uncanny valley", but they are sneakily influencing consumers' purchasing decisions.

Virtual or avatar influencers are computer-generated imagery (CGI) characters created to execute marketing campaigns, acting as a brand's "ambassador" or "spokesperson", just like human influencers and celebrities do.

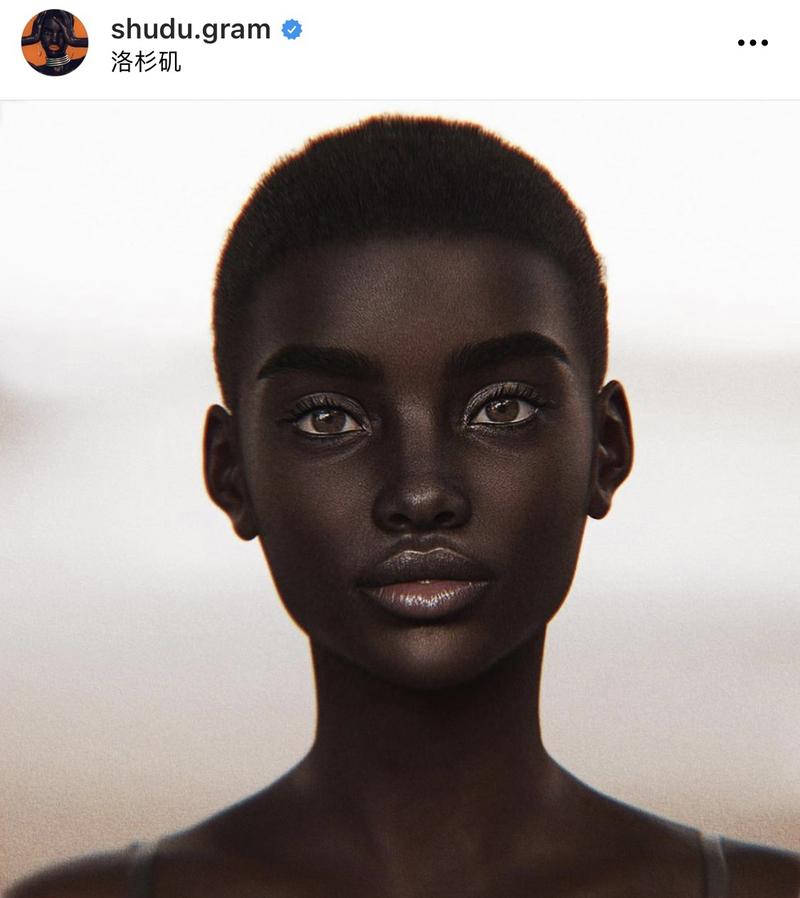

Among the most starry virtual influencers is Lil Miquela, created by Los-Angeles-based startup Brud - a group of problem solvers specializing in robotics and artificial intelligence. The robot has so far racked up 3 million followers on Instagram, having teamed up with such world-renowned designer labels as Prada and Dior. Shudu, claimed to be the world's "first digital supermodel", boasts having more than 230,000 Instagram followers and has promoted luxury brands like Chanel, Bulgari and Balmain. Bermuda is a politically controversial one and musician, having produced albums to keep her fans entertained and infatuated.

More brands and marketers are gravitating toward creating digitally generated influencers for marketing campaigns for a host of legitimate reasons.

First and foremost, it allows brands great flexibility and control. These virtual ambassadors can "attend" multiple events simultaneously and at the brand's disposal 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, compared with real-life influencers who have fixed working hours and can't physically travel across the world in a day for various activities.

Virtual influencer marketing is notably cheaper when it comes to photo shoots or travel, says Andrew Hutchinson, an award-winning blogger, author and social media marketing analyst. "There are costs involved in creating top-notch digital images, but they would still be far lower compared with a major celebrity campaign," he says.

When virtual ambassadors are created by artificial intelligence companies, "they are brand neutral, involving no personal opinion to consider in taking on a deal", says Hutchinson. It could be a different story if they're invented by brands. On one hand, it's less unpredictable to use artificial intelligence influencers who are unlikely to go off-message, misinterpret or distort brands' information because the yarn is orchestrated by the brands. Brands have greater control over the information in promoting the content.

On the other hand, if the virtual muse is the brand's brainchild, the narrative is constructed in favor of the brand and, therefore, "anything but neutral", argues Hutchinson. In that case, it's more about self-promotion than influencer marketing.

It's not a hypothetical statement because many brands have given birth to their own avatar influencers. Prada introduced Candy, a freckled, purple-eyed, stylish girl for its fragrance line last year, who has featured in short videos, Twitch, TikTok and print covers. Candy's presence in the advertorial video has stirred conversation among viewers, with mixed feedback. For some, the virtual poster girl breathes new life into conventional influencer marketing that has been taken for granted. One comment reads: "My god, this is so amazing!!! Please keep her as a model and not just for this spot! The best advertisement I've seen in the past years!". Another goes: "Is she supposed to be a virtual influencer? I just get the vibes. Prada, this advertisement is amazing! I don't wear perfume, but I still want one now. Very well done!". For some, however, Candy is too artificial to believe. A viewer laments: "Kinda disappointing to see that in 20 years, exactly nothing has changed about CGI characters", while another dismisses the perfume commercial as "smelless and soulless".

Whether the reaction is positive or negative, the discourse among viewers has attracted the brand's attention.

Multiple versions

There is a spectrum of virtual influencers - a 100-percent CGI avatar, a purely organic real person avatar and something in between.

Puma introduced Maya to its Southeast Asian market last year to promote its "Future Rider" shoes collection. The design team used artificial intelligence to map millions of faces from Southeast Asia, superimposed various faces representing different peoples of the region on the model, resulting in multiple versions of Maya that appeal to all customers across the region.

The initial cost of creating an AI influencer from scratch could be expensive as it involves plenty of research and development. But as the formula is established, generating more iterations will be much cheaper and easier, says Phan Tuan Quang, associate professor of innovation and information management at the University of Hong Kong. This pattern is mirrored in industrial production, where the initial investment or fixed cost of producing a car from the drawing board, for example, is high, but the cost of manufacturing every additional unit - marginal cost - is dramatically lower.

So, each existing virtual influencer can produce numerous virtual spinoffs that are savvy in different niches and can generate varied storyboards targeting specific demographics. It is a process of extending the micro-influence of virtual influencers with a low budget, says Phan.

"Right now, because of the publicity and novelty, many virtual influencers are seen competing against top-tier (celebrity) influencers. But, down the road, because of the cost structure, I think we will see them pitting against micro (human) influencers," he says.

When a brand opts to bestow an exhaustively compelling life narrative on its virtual character to continuously grow in sync with the brand, the alignment of a "product cycle" and a "character lifecycle" is forged. This is instrumental for the brand to leave a deep mark on its fan base, reckons Didi Pirinyuang, executive creative director at Ensemble Worldwide, who was involved in the creation of Maya. Such an alignment is hard to come by in human influencers.

Maya, however, just has a seasonal character life cycle. "They (Puma) launched a new line of sneakers and sought a brand-new personality representing the collection," Pirinyuang says. But it doesn't mean Puma will overgrow Maya because one Maya can "give birth to" a range of "Mayas" with nuanced traits to represent different collections of Puma shoes in future. In that way, Maya's life cycle is extended in tandem with Puma's. "So, at the moment, Maya is on holiday," quips Pirinyuang. "We give her a respite until the brand is ready to launch a new collection."

People follow influencers because they're enamored with or related to the influencers' personalities and "histories" - where they came from, what they did and what they represent, Phan notes. It's the emotional attachment that gives influencers "social capital" which is then utilized by brands for marketing purposes. "This is not only the beauty of (human) influencer marketing, but also the drawback," Phan says.

The more recognized influencers are, the more public scrutiny they're subjected to. An example is Viya, the top Chinese livestreamer and influencer who was prosecuted for tax evasion. So, there is a duality in influencer marketing, Phan argues. "The delicate balance is brands collaborating with influencers, cashing in on their social capital which may also become a liability later on."

Virtual influencer marketing, in comparison, allows brands to craft the fictional persona from scratch, without history, says Phan. "They can curate a virtual being exactly the way they want." Hence, there is less risk of liabilities that accompany popularity. Nevertheless, the lack of "history" in those virtual characters could cause confusion and emotional distance among the audience who would then choose not to follow.

Carefully curated

Early criticisms of AI influencers have revolved around its "inauthenticity". These artificially made influencers "may not show their weakness and vulnerabilities", explains Phan. There is little human touch in them. Whereas, human influencers, with flesh and blood, are more genuine although their story arc on social media could also be carefully curated.

Virtual marketing influencing is just in its nascent stage, with tricky issues to contend with. Among them is the lack of transparency.

While some influencers make an explicit statement about sponsored content, many don't, leaving the audience in the dark because there are no binding rules currently to enforce the practice. Even though the posts are labeled clearly as advertising, "how much money is offered to the influencer is unknown", adds Phan, suggesting that a generous budget could render the sponsored content less genuine.

The unregulated use of "synthetic versions of real people" or deepfakes and virtual influencers has spawned a crop of videos that are ostensibly benign but essentially misleading and deceptive. For example, David Beckham is seen speaking nine languages in a video for a malaria awareness campaign, which turned out to have been fabricated by an AI startup. In worse imaginable scenarios, ill-meaning deepfakes can be used to spread rumors and political propaganda.

Responding to the thorny issue, Meta Platforms, formerly Facebook, says it will introduce ethical boundaries in the application of AI figures.

The well curated virtual influencers, often blessed with porcelain skins, flawless features and perfect body shapes, have triggered raging criticism that their impeccable constructs may feed into the unrealistically ideal beauty standards plaguing mostly women and teenagers. This toxic culture, which has existed since the advent of social media and has been fueled by the omnipresence of Photoshop tools, is responsible for mental health issues, such as body dysmorphia, low self-esteem, negative thinking and self-identity problems with grave consequences.

But Phan is not that pessimistic. Virtual influencers aren't culprits of the aberrant culture, he says. Instead of perpetuating unhealthy aesthetic values, he believes that virtual influencers, with their plasticity, can be game-changing for counteracting the culture. We've started to see individuality prevailing in some Asian cultures, says Phan, "with people from South Korea and Japan seeking plastic surgeries for impactions, such as crooked teeth or fangs instead of straight white teeth. People are looking to distinguish themselves from others". If creators can customize flaws on their AI muses, virtual influencer marketing will be a perfect vehicle to celebrate natural beauty, Phan reckons.

Among the pioneers is the Chinese CGI creator Jesse Zhang, whose brainchild Angie has uneven skin with acne scars visible on her blushed face, wears pajamas, and likes yawning. She has more than 300,000 followers on Weibo and Douyin.

Apart from building in some flaws on the digital characters, "there should also be regulations for disclosure on digitally altered images, making it clear that this is not realistic, which could reduce unhealthy comparisons", concedes Hutchinson.

On the one hand, it would be difficult to enforce, "given the way in which these virtual images are created", he says. Nevertheless, he acknowledges, the percussion of non-disclosure on virtual characters could be less damaging than that of the over-the-top photoshops that people apply to their online pictures, as the former are clearly fabricated while the latter is an actual person.

Looking into his crystal ball, Nicholas Chan Hiu-fung, a partner at global law firm Squire Patton Boggs and an expert in AI-related regulatory compliance, said he predicts that the increasingly sophisticated computer algorithms will lead to a crop of more humanized virtual influencers who deliver the best tailor-made experiences to consumers. Through social media profiling, the AI influencer will be able to identify each online viewer's needs, preferences and even characteristics before getting into a dialogue with its audience. Not only will there be a deeper sense of kinship in avatar influencers, they will also be able to provide more customized purchasing recommendations to individuals. The prospect of highly humanized AI influencers is the harbinger of our real and virtual worlds overlapping more and, ultimately, we will be edging toward a parallel space-time universe, thanks to the rise of the metaverse.

At the end of the day, virtual influencers will make shopping in brick-and-mortar stores a personalized and immersive experience. The more engaged you are in the virtual influencer's metaverse, the better he or she understands you, says Chan, whose firm's core legal disciplines include intellectual property and data privacy.

"Then the influencer can share the knowledge about you with, say, an offline cosmetics store (with your consent) so that the service will be bespoke."

- China widens net in battle against graft

- New US dietary guidelines trigger widespread concern

- China eyes space leap with record satellite filings

- Team formed to investigate the loss of 29 cultural relics

- Investigation into school uniforms confirms safety of waterproof layer

- Taiwan students join winter sports exchange in Tianjin