Paging the book doctors

In the last decade, great strides have been made by the nation's top institutions to ensure that China's ancient texts are preserved for generations to come, Wang Kaihao reports.

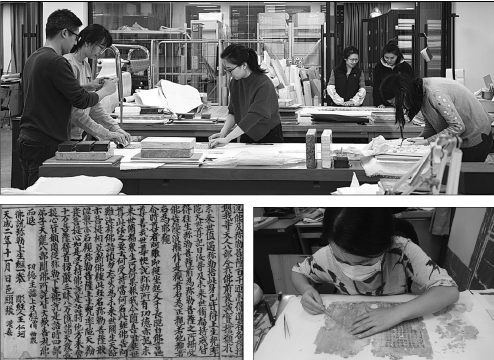

For Tian Tingting, aged books sometimes resemble stale puff pastry. Often suffering from water damage, or having been snacked on by bookworms, the centuries-old pages are crispy and rotten, and in many cases, stuck together.

"They are too fragile," Tian says. "You can't be too careful when separating them."

She is a book restorer at the National Library of China, the world's biggest repository of ancient Chinese books. More than 2.7 million such books-defined as those published before the fall of monarchy in China in 1911-are now housed at the library.

Sometimes, the restorers behave more like chefs. For example, an old but efficient way to separate the pages is to steam them in a pot for six minutes, no longer and no less. Then a small bamboo stick and patience will help to split them apart.

Steaming can also help Tian carry out other restoration procedures. Once new paper is used to replace the rotten part of an ancient book, that same "cooking" method can greatly accelerate the aging process, giving the repair the patina of an aged appearance.

Nevertheless, in the restoration of ancient Chinese books, the basic principle is to maintain the original appearance of the book as much as possible with the minimum necessary intervention.

"So, in most cases, a page is merely partially fixed," Tian says. "Only when a page is severely damaged, we'll consider remounting the whole piece of paper for consolidation."

On April 16, Tian enjoyed a career highlight when her restoration of a copy of Tangwencui-"a collection of fine Tang Dynasty (618-907) prose"-from the 1520s won her the first prize in the national competition of ancient book restoration, which was awarded in her home library.

Launched by the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books, it is the first such national competition since the founding of New China in 1949.

"The written classics have borne our civilization for thousands of years and have been passed down for generations," Rao Quan, director of National Library of China, said at the award ceremony. "But they have always faced danger, ranging from war to worm. The restorers, therefore, play a vital role in the conservation of the books and prolonging the linage of Chinese literature."

Five outstanding projects from the National Library of China, Tianjin Library and Shanghai Library were awarded the top honor, while 10 received the secondary award and a further 21 received a third accolade.

Nearly 100 restoration projects from 21 provincial-level administrative regions entered the final competition, and the result was decided by a 16-person judging panel, composed of the country's top-tier restorers and librarians of ancient texts.

Speaking of the criteria judging the restored books, Zhang Zhiqing, deputy director of the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books, emphasizes the importance of the guiding mindset more than a relatively intact appearance of the restored book.

"We'd like to see the restorers maintain a rigid and careful attitude toward the paper relics," Zhang says. "Old books should look old. We do not expect to see something overdone just to show off technique."

To avoid regret, caution is needed in restoration, especially when it comes to some priceless national treasures.

Among all the awardees in the competition, the work by Hou Yu--ran and her team from the National Library of China's restoration department was, arguably, the most important.

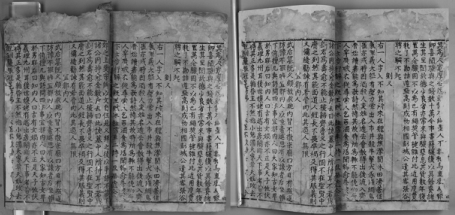

The 1.23-meter-long scroll, The Bodhisattva Maitreya's Previous Life in Tusita Heaven (first volume), was printed in 927 and came into the library's possession in 2015. The sutra is the world's second-oldest known dated printed work, only after the Diamond Sutra printed in 868, which is also a Buddhist scripture from China and now part of the collection at the British Library.

"It's a rare example of early-stage printed work," Hou says. "But its condition was complex when it was handed to us. It was broken, and its color was fading."

By analyzing the material, an ancient papermaking method using the bark of mulberry trees was adopted to produce new paper to make patches. An even bigger challenge was water stains on the scroll. In Hou's experience, it takes strong chemicals to get rid of them.

"For the safety of the paper, we decided not to pursue 'perfection' and left the stains there," Hou says. "People in the future will also be able to better understand what the scroll has experienced. It's key historical information as well."

In many cases, restorers find their work to be akin to a dialogue with their predecessors. Hou recalls finding a previous patch on the back of the scroll.

"Judging by the color and material, that restoration would not have been too long after this work was printed," Hou says. "But the way it was attached was sort of careless, so it had crumpled. The best way to deal with it was to simply make it flat and leave it in its original place."

New chapter

In the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) book Zhuanghuangzhi, or "a record for decoration", which focuses on the mounting of paper works onto bindings or scrolls, the author Zhou Jiazhou wrote: "Restoration (of ancient books) is like seeing a doctor. If the doctor is good, your illness will be gone immediately following the treatment. But if not, you may die taking the medicine. So if you cannot meet a good craftsman at that moment, you'd better keep your item as it is."

Consequently, it has become a motto among Chinese restorers of ancient books "to prolong the life of books is like being a good doctor".

Nevertheless, a good doctor may not be that easy to find.

By the time the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books was established in 2007, there were fewer than 100 full-time restorers of ancient texts in China, which left a huge gap for protection of the myriad precious pages.

"In the old days, the nurturing of restorers used to rely on the method whereby masters would guide apprentices," Rao explains. "It took years or even decades to train a qualified restorer this way."

It is estimated that at least 30 million ancient books are housed in China's public institutions, according to an ongoing national census by the national preservation and conservation center. Reality has prompted change.

According to Zhang, the deputy director of the center, 65 training sessions have been organized by the institution, and 12 regional training centers for ancient book restoration have been established nationwide.

The traditional master-apprentice inheritance method has also been retained. Restoration of ancient books was inscribed on the list of national-level intangible cultural heritage in 2008, and 32 tutors hired by the national preservation and conservation center, who have recruited 270 apprentices.

"Now, we have about 1,000 full-time restorers around the country," says Zhang. He says he is excited when recounting the statistics, adding that over 3.6 million pages of ancient texts have been fixed in the past decade.

Science and skill

Most awardees of the national competition, like Tian and Hou, were born after 1980.

"It's great to see restorers of ancient books don't have to be someone in our age," says Du Wei--sheng, 69, a veteran restorer who has worked at the National Library of China for nearly half a century. "Young blood is the key for revival of the traditional technique, and they usher more scientific approaches in restoration."

As restoration of books was for a long time simply considered a craft, which relied on experience rather than education background, none of the 100-some restorers, including Du, had bachelor's degree.

A sharp contrast among today's younger restorers is that, in recent years, many graduate students who majored not only in the arts and history, but also natural sciences, including biology and chemistry, entered the industry.

"Today's restoration needs comprehensive expertise, which is also reflected through the awardees," Zhang adds. "Scientific research plays a bigger and bigger role, which almost equals the importance of traditional craftsmanship in restoration."

For restoration of a Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) book on the appraisal of antique bronzeware, which also won the second prize in the recent national competition, restorers from the Fudan University library in Shanghai collected over 3,000 pieces of relevant data from the paper when drafting a tailored restoration plan.

From the viscosity of the glue and the possible influence of dyes, to the color difference between original pages and prepared new materials, analysis in the library provides a convincing reference to make the best choice.

And, in Shanghai Library's awarding-winning project, restorers did experiments to explore suitable dyeing ingredients to yellow the newly added paper in a natural way. They got the best formula by mixing black tea, plant seeds and minerals from traditional Chinese painting pigments.

"In the past, only previous experience told us what should be done and what shouldn't, but we didn't understand why," Du says. "Now, research in the lab can provide an explanation and more creative solutions."

Older restorers have their regrets. The 900-year-old Zhaocheng Jin Tripitaka, one of the pillar collections of ancient books of the National Library of China, was restored between 1949 and 1965. It was the first, and among the biggest, ancient book restoration projects in the history of New China, but not a single character written about how it was restored remains.

"I really admire today's restorers' approach of keeping detailed logs of every step in their work," Du says. "The reference will hugely benefit such work in the future."

Today's Top News

- Wake-up call for Europe to review its dependency: China Daily editorial

- China reports 5% GDP growth in 2025

- Return capsule of Shenzhou XX safely returns to Earth

- Sanya rises as magnet for Russian tourists

- China's steady opening-up for Asia-Pacific economic growth

- Blueprint seen as a boon for entire world