Springtime pollens put people on allergy alert

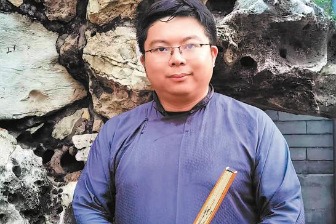

As the temperature warms, leaves turn green and flowers bloom. But Beijing resident Zheng Gaoshan, 38, doesn't enjoy the spring scenery much, as outings often end up with a lot of sneezing, a stuffy, runny nose and itchy, swollen eyes.

Zheng is one of more than 250 million Chinese people with allergic rhinitis.

"Every year from March to April, I have to take a number of anti-allergy drugs and use nasal spray and eye drops to ease the symptoms, which seem to have worsened over the years," he said. "If I don't take any countermeasures, my eyes might not be able to open. It's like they are being filled with smoke in a barbecue booth."

Zheng was tested for around 30 allergens at a hospital in 2018.Results showed his allergy was caused by Sabina chinensis, a type of cypress and a common evergreen plant in the city.

"I won't visit any parks or mountains in the spring to keep away from the plant, but encountering them on the street is unavoidable," he said.

Every spring, when the pollen concentration rises, the nose and throat departments of hospitals are packed, as pollen has become the major cause of allergic rhinitis for many Chinese, according to a recent survey by Beijing Tongren Hospital.

The incidence of the disease has been growing in China in recent years and now affects 18 percent of the population, the hospital said.

"Allergies are closely related to the economic development level of society," Zhang Luo, the hospital's president, said. "In less-developed countries, children contact bacteria and viruses in the environment more often, which promotes their immune system, so they are less likely to experience allergies when they grow up.

"Allergic rhinitis has steadily increased in China, especially among children and young adults. As the economy develops, more Chinese will have the disease."

In Beijing, the most common allergenic pollens in spring include those from the large-fruited elm tree, Cathay poplar, ash, acacia and white birch. Pollen concentrations recently reached their highest or second-highest level in the city's six-tier rating system.

"As the country enters pollen season, self-protection and targeted treatment are important," Zhang said. "For example, when the concentration is high, patients should reduce their outdoor activities and wear face masks and goggles when they go out. It's helpful to take immunity-modulating drugs in advance before symptoms appear and continue to use medicines based on a doctor's guidance until the pollen season passes."

Most allergens are closely linked to the environments people live in and are impossible to simply wipe out, he said, adding that including allergic rhinitis in the national chronic disease supervision, prevention and treatment system would help, as would planting flowers, trees and grasses in city landscaping that induce fewer allergic reactions.

Sublingual immunotherapy-which places small doses of allergens under the tongue to increase tolerance and reduce symptoms-has been approved by the National Medical Products Administration, Zhang said. The therapy will benefit a lot of patients allergic to artemisia pollen in northwestern areas, he said.

With the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics approaching, Zhang's research is focusing on nasal inflammation caused by dry, cold air, to offer diagnosis and treatment for athletes who may encounter the problem.

Research by Zhang on allergic rhinitis was published in February in a special China edition of Allergy, the world's top medical journal specializing in the area. The 73-year-old journal published 23 papers by Chinese experts on topics such as allergy science, nose science, respiratory medicine and COVID-19.

- Lantern Festival lights bring the Dunhuang grottoes to life

- China's 2026 Spring Festival travel rush to begin

- Knocking on the stone-framed door

- Shanghai Science and Technology Museum to reopen soon

- Shanghai celebrates Spring Festival with intl students

- Pegasus fondant artwork ushers in Year of the Horse in Shanghai