A son of the West whose passion pointed East

Colleagues, family members recall intrepid days of Ezra Vogel, renowned author and scholar on East Asia who stayed active up to his death at age 90. Zhao Xu reports from New York.

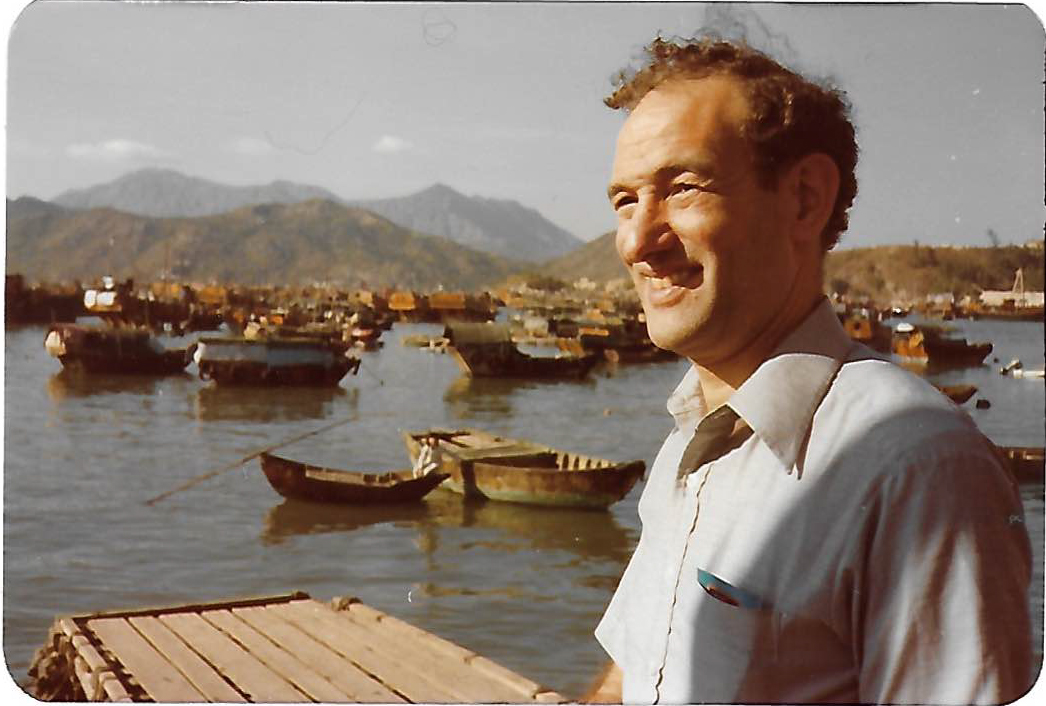

David Vogel, adjunct lecturer of psychology at Merrimack College in North Andover, Massachusetts, always remembers the way his father "looked longingly" toward the Chinese mainland, while the two were on the Hong Kong side of the divide in the mid-1960s.

That was the time when the island was still a British colony and one of the only two places, the other being Taiwan, for a Western scholar wishing to study Chinese society.

"When my father was able to go to the mainland a decade later, it was like finally meeting someone with whom you had been on the phone for years, someone you really want a relationship with," he said.

It was a relationship that had lasted till the end of the man's life, for nearly half a century. On Dec 20, Vogel's father, the internationally renowned East Asian scholar Ezra Vogel, died in Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts, after having surgery for colon cancer. He was 90.

The news was announced by the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University, where Ezra Vogel served as director between 1973 and 1975 and then between 1995 and 1999. It also hit headlines from China to Japan, two countries whose languages Vogel spoke and whose stories he helped to tell.

Yet to many who had crossed paths with Vogel, his passing seems itself like the ending of a long, compelling novel: the timing, while not entirely unexpected, has been rendered all the more abrupt by the sheer pace and excitement at which the later plots had unfolded.

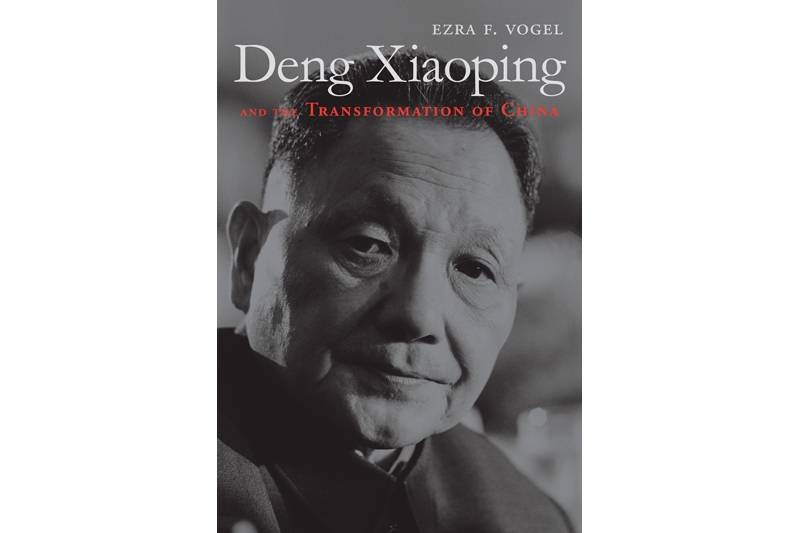

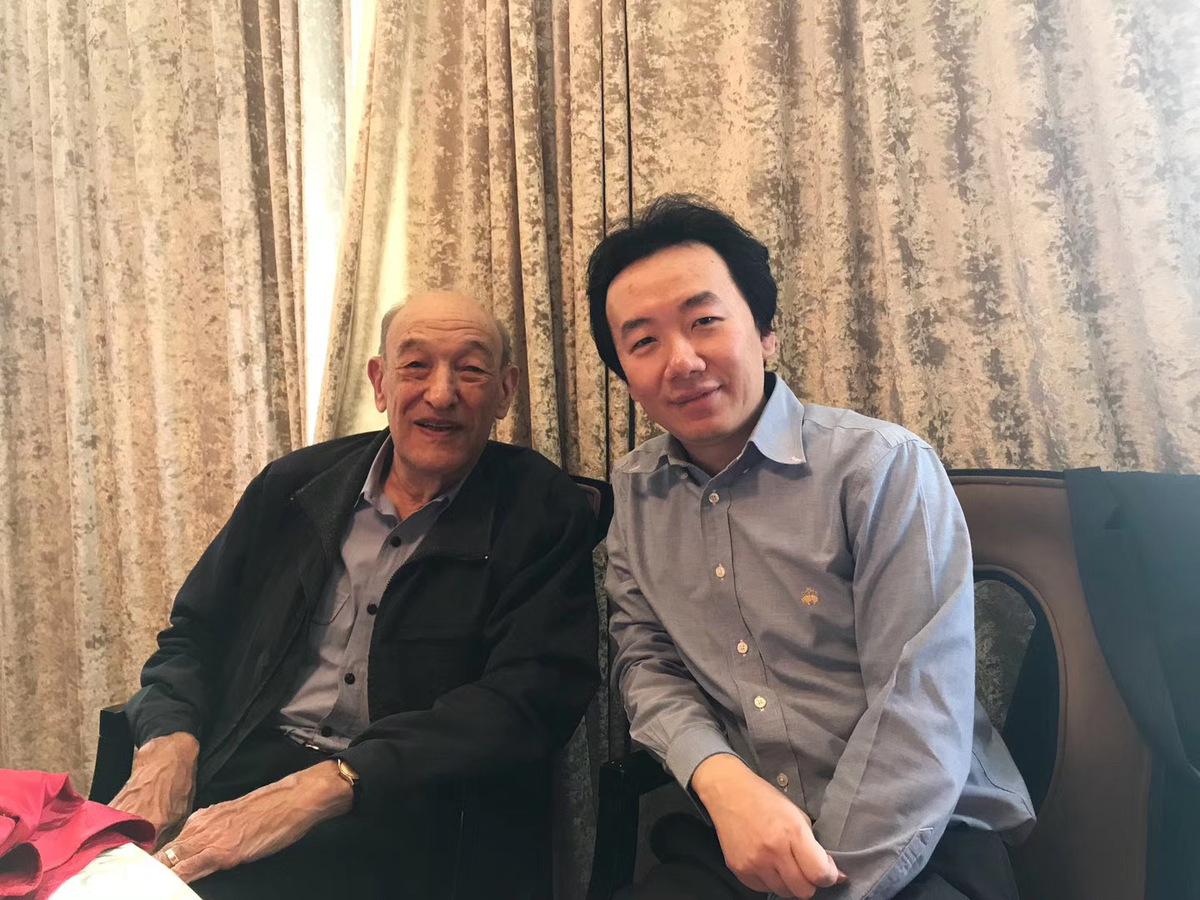

"It's unlikely that we'll have another man like him, an American scholar with equally profound knowledge in China and Japan," said Ren Yi, a Harvard graduate who assisted Vogel during his decade-long writing of the definitive book Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China.

The book, published in 2011, when Vogel was 81, is a culmination of Vogel's efforts to tell the ultimate story of modern China, one of a dramatic transformation directed by one man and resulting in 300 million of his compatriots taken out of poverty.

"Here you have it: utter disregard for disciplinary boundaries, scant attention to grand theory, no respect for methodological orthodoxy," wrote Steven Vogel, Ezra Vogel's younger son and a political scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, as he paid tribute to his late father. "The only common thread: work hard, talk to people, listen carefully, get the story right."

Jan Berris, Vice President of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations in New York, knows all about what she calls "Ezra's energy, stamina and tenacity". A year ago, the two were in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, the last of the many trips Vogel made to China since he first went there in 1973 on academic exchange.

"When we were deciding who we should meet, Ezra came up with names of people he had interviewed more than three decades ago," said Berris, referring to Vogel's eight-month stay in the city in 1987, at the invitation of the Guangdong provincial government. (Guangzhou is the capital city of Guangdong.)

The goal was to study the province's economic and social progress triggered by China's economic reform launched in 1978, and the result was Vogel's 1989 book One Step Ahead in China: Guangdong Under Reform. Charlotte Ikels, an anthropology professor and his wife of 41 years, was also there for her own research.

"He spoke Mandarin and I spoke Cantonese, the local dialect. And his interests were primarily policy implementation at a macro level while I was looking at the impact of economic change on the elderly and family life," Ikels said. "So he would do his interviews in Mandarin with government officials and factory managers, and I would do mine in Cantonese with older people and sometimes younger family members.

"Between us at the end of the day, we would compare notes and talk about what we actually saw. I think that was very valuable because he was not stuck at one level."

The first time the couple went together to China was on their honeymoon in late 1979, along with a group of Harvard alumni and Vogel's two sons from his previous marriage, 23-year-old David and 18-year-old Steven, who were in China for the very first time.

Today, David Vogel still recalls the time when some members of their group left tips at a restaurant table, before "the waitress came to chase them with the money they left".

The young man was treated to a Peking Opera performance in a military tent. "It was winter, so everybody was cold. And folding chairs were brought in for the elders to sit comfortably in," said David Vogel, who would return to China in 2004, where he watched another performance, this time in a big opera house, and missed the earthiness of the previous experience.

"Back in 1979, there was this palpable feeling of the beginning of change, which my father always admired," the son said.

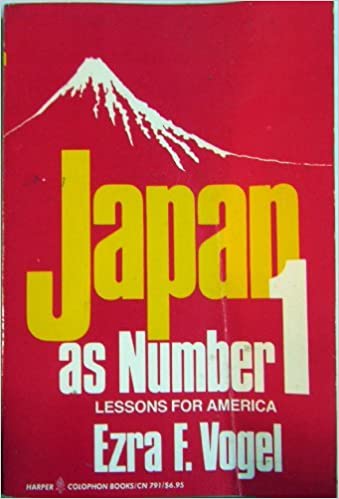

And it was reminiscent of the thrill Ezra Vogel felt while in Japan in the 1960s and '70s, years leading to the publication of his milestone 1979 book Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, a book that established Vogel as a trenchant observer and an authoritative voice on US-Japan relations.

Set against Japan's rapid economic growth in the '60s, the book sought to unlock the secrets behind Japan's phenomenal rise to become the world's second-largest economy in 1968, right behind the US and upsetting many in this country.

"The way Professor Vogel approached the issue — from a multitude of perspectives and with thoughtful attention to Japan's historical and cultural roots — has not only effectively conveyed the Japan lesson, but also managed to bring the two countries together by helping one to truly understand the other," said Ren, today an influential blogger and commentator in China, under the online name Chairman Rabbit.

"Both the Americans and the Japanese thanked him for what he'd done for them."

Son of Jewish immigrants Joe and Edith Vogel, Ezra Vogel grew up in the small town of Delaware, Ohio, where his father ran a men's and boy's clothing store. Eve Vogel, daughter of Ezra Vogel, believes that the early intercultural experience — the Vogel family was one of the five Jewish families in that mostly Methodist town — had given rise to her father's lasting interest in foreign societies.

Being an effervescent, hard-working and generous person, Joe Vogel, who gave things anonymously to help the Boy Scouts and orphans, also influenced his son.

In a tribute carried by The Japan Times, Steven Vogel, who had attended boarding schools in Japan as a teenager before becoming a Japan specialist, described his late father as possessing "boundless good cheer and boyish enthusiasm". "He had an irrepressible ability to see the good in every person and every nation, while recognizing nonetheless that many of us fall short of our ideals," he wrote.

Another shaping force was the era in which Ezra Vogel found himself.

"Growing up during the Great Depression, Dad witnessed what the federal government could do to build an economy and help everyone, as in the form of President Roosevelt's New Deal," said Eve Vogel, professor of geography at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. "Later, he thought what he could do to help spread the positive lessons and build economic progress, something he did with both Japan as Number One and with the Deng Xiaoping book."

After graduating from Ohio Wesleyan University, where Ezra Vogel studied sociology and anthropology, the man, with a strong interest in psychology, worked for two years for a psychiatric unit of a military hospital, an experience that might have helped develop his aptitude for trust-building.

But it was not until Ezra Vogel entered Harvard and met his doctoral thesis adviser Florence Kluckhohn that his vision started to expand.

"If you want to look at American society objectively, you really have to go abroad to a different culture," Kluckhohn is believed to have said to her student.

Between 1958 and 1960, Ezra Vogel devoted two years to language study and field research in Japan, a country where "he could really not live in the big cities while still be assured of good medical care and hygiene to raise a baby", to quote David Vogel, born in 1956.

In Japan, Ezra Vogel worked alongside his first wife, psychotherapist Susan Hall Vogel. (Susan Vogel is the mother of David, Steven and Eve. The couple divorced in 1978 and she died in 2012 at the age of 81.)

"They were supposed to do ethnographic and psychological studies. But from talking to people and listening to everything around him, my father soon realized that what was most exciting about Japan at the time was its economic and cultural transformation," David Vogel said.

Being "flexible and responsive" as an intellectual, Ezra Vogel changed directions, eventually coming up with the 1963 book Japan's New Middle Class, thus beginning his half-century-long examination of Japan's society and economy.

Around the same time, advice came from John King Fairbank, venerated China scholar after whom the Fairbank Center is named and to whose directorship at the center Vogel succeeded. Fairbank suggested that Vogel study China — the language and the country — if he were to tap fully into his own potential and firmly establish himself at Harvard.

Vogel heeded the advice and went to Hong Kong, bringing with him David, who attended prep school there. In retrospect, the son believes that the change of focus (from Japan to China) in the late '70s and '80s reflects his father's lifelong infatuation with "a dynamic, transformative energy" heralding big societal changes.

"As Japan began to stagnate, he moved his attention to China," he said. "He sought to announce China's arrival the same way he did Japan."

In fact, it's fair to say that Ezra Vogel has been dividing himself academically between China and Japan since the 1960s, alternately penning books on each of them. His final book, titled China and Japan: Facing History, published in 2019, looks at the two countries' bitter history and fraught relationship in an effort to bring them into the future.

"Future is what Professor Vogel had always been wishing for the two countries with which he had the strongest emotional ties," said Ren, who first visited Vogel's three-story family house in Cambridge in the early 2000s. "His study was in the basement. It's dimly lit and filled with books. Sequestered in a corner, the writing desk was almost entirely overtaken by books, leaving barely enough space for a laptop."

In 2000, Vogel started working on Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, a book that would introduce him to a wider Chinese public.

To upgrade his spoken Chinese, Vogel worked with a tutor for a year. The professor later said, not without a sense of pride, that except for his talks with a couple of English-speaking people, all the rest of the interviews for the book were conducted by him in Chinese, with the presence of no one else but him and his interviewee.

"If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart," Nelson Mandela once noted. Vogel, who "understood the difference between what's been said and implied", to use Ren's words, was a firm adherent of that saying.

Ren Yi, the grandson of Ren Zhongyi, former governor of Guangdong province, was instrumental in setting up some key interviews for Vogel, with children of those within the country's first-generation leadership. It is also worth noting that Guangdong became a sister province of Massachusetts in 1983 during the rule of Ren Zhongyi, whom Vogel called a "remarkable reformer" and interviewed for his book on Deng.

"Thanks to the sister-province relationship, people at the provincial government level came to the Boston area from Guangdong. Ezra met many of them, some later becoming state leaders," Ikels said. Vogel dedicated the Deng Xiaoping book to her and Chinese friends of his. "On the other hand, Ezra also mentored and befriended many Chinese who came through Harvard over the years."

Some were invited to the dinners hosted by the couple in their home, called "the second Fairbank Center" by Michael Szonyi, the center's incumbent director and professor of Chinese history at Harvard.

"They would order takeout Chinese food, and we would help ourselves in the kitchen," wrote Szonyi in a memorial article after Vogel's death. "You never knew who would turn up at such events — senior scholars from around Asia, major government leaders, people who Ezra had met somewhere in his long career … he clearly thrived and derived much energy from always being around other people."

For years Erza Vogel acted as an adviser to the National Committee's Public Intellectuals Programs, aimed at "nurturing the next-generation of China specialists".

"Ezra never showed off," said Berris, Vice President of the committee and the program organizer. "He talked about people, not himself. Every time he traveled to China with us, Ezra made sure that he spent at least an hour or two with every single member of the group, starting to take notes a few minutes into the conversation."

The same treatment was given to students who, in their second year at Harvard, chose to specialize in East Asian studies, according to Ikels. "He read their files so that he knew them all when they went individually into his office for one-on-one meetings to talk about their interests and families. They made them feel important," said Ikels, who first met Vogel when the two were doing research in Hong Kong in the '70s.

"I was a graduate student and he was a professor. There was this American-sponsored place called the University Service Center. One day, someone put a sign up on the bulletin board at the center saying that he'd be happy to discuss with any student his or her research project. And I signed up," Ikels said. "In all of the time he was really the only person who was relatively senior and offered this to students."

The couple stayed in Beijing intermittently in the 2000s while Vogel worked on the Deng Xiaoping book (Vogel also visited all the Chinese places where Deng spent prolonged periods, including his birthplace, to which a Vogel family trip was organized in 2016.) In their spare time they sampled authentic Beijing by biking along the ancient Chinese capital's age-old alleyways.

"He rode his bike for 4.5 miles just five days before he went for the operation," said Ikels, who biked with her husband three times a week for the last 20 years.

Looking back, Eve Vogel believed that her father, with his humble background, was once "stretched out" trying to prove himself at Harvard and to "basically become a China specialist in three years". "He stopped feeling insecure after the publication of Japan as Number One," she said.

Before going into surgery on Dec 14, Ezra Vogel called his son David. "He called just to talk about my life. And he apologized for being extremely busy and often not around in my early childhood. He thought worse about it than I did," David Vogel said. "My father continued to grow and change as a person throughout his life, always trying to be more aware."

In the US and China, the death of Ezra Vogel is mourned as the loss of "a major supporter of the effort to inject greater sanity and balance into US thinking about China", to quote Michael Swaine, director of the East Asia Program at the Quincy Institution for Responsible Statecraft, a Washington think tank.

On July 23 last year, the US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo delivered an incendiary and controversial speech at the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, declaring US engagement with China a failure.

One day before that speech, Vogel published an article in The Washington Post titled "US policies are pushing our friends in China towards anti-American nationalism". Echoing an opinion piece posted by Ren on his own blog, Vogel argues, among other things, that the US attack on the Chinese Communist Party and its decoupling policy — ending the Fulbright program, for example — was alienating China's intellectual elite both inside and outside the party.

"I can tell you that many who had fought to respond to American requests and felt proud of their successes in adopting international standards — often against domestic resistance — feel as if their valiant efforts and successes are seen by prominent Americans as worthless," he wrote. "Many are members of the Communist Party."

The Vogel article came on the heels of an open letter signed by him, Swaine and a number of others and published by The Washington Post in early July.

"US opposition will not prevent the continued expansion of the Chinese economy, a greater global market share for Chinese companies and an increase in China's role in world affairs," the letter said. "Moreover, the United States cannot significantly slow China's rise without damaging itself."

As someone who had tried to ease the US reaction to a rising Japan in the 1970s with a book, Vogel in his later years was "obviously deeply troubled", to quote Szonyi, by the growing antagonism in Washington toward China, which overtook Japan to become the world's second-largest economy in 2011.

"Professor Vogel's knowledge of China and Japan enabled him to look both beyond and behind the apparent political and ideological differences, to see their cultural kinship and parallelism. Consequently, he believed that the rise of China was essentially no different from the rise of Japan decades earlier, a view shared not by many in the US," said Ren Yi, who maintained correspondence with Vogel until his death.

"Living through the Cold War as a budding young intellectual allowed him to see the temporal and contingent nature of ideological labeling, a practice that dominated the era."

A perpetual encouragement to his fellow American scholars disheartened by the current bilateral relationship, among them Szonyi, Vogel reminded them that many in his generation "could not go to China for decades".

"The important thing is for us to take the long-term view … to ignore immediate political winds and concentrate on our scholarship," he said.

Ren Xiao (no relation to Ren Yi) is the director of the Center for the Study of Chinese Foreign Policy at Fudan University in Shanghai. He saw Vogel, in his adoption of a multidisciplinary approach and his insistence on field research, as embodying a tradition no longer valued by a young generation of US scholars as it should have been.

"The current trend in social sciences study in the US is for researchers to become increasingly specialized in a narrow discipline of their choosing. As a result, one researcher cannot be reasonably expected to understand, let alone discuss, the treatises of another one unless their research focus is almost identical," said Ren Xiao, who met Vogel several times in China and the US.

"And it doesn't help that the articles themselves are interspersed with abstruse academic parlances, mind-boggling numbers and grand models developed in hope of being applicable to all situations and societies. This tendency to make projections or draw conclusions without first-hand knowledge has produced distorted, highly misleading pictures.

"Vogel, for his part, recognized the subtleties of cultures and therefore the importance of ground research. Empathetic, he embraced his research subject rather than keeping them at arm's length, and was always looking for things that couldn't be summed up by numbers."

In the preface for the Deng Xiaoping book, Vogel talked, with typical humility, about the privileges he had as a leading Western scholar on China to be able to get the interviews and write the book. When Jiang Zemin, China's president at the time, visited the US in 1997, Vogel hosted him at Harvard, before interviewing him for the book.

"Ezra saw Deng as the person who gave China the permission to change," said Ikels, who described herself as a "sounding board" for her husband, who often discussed matters with her during the writing of a book. "Instead of offering his own criticism, Ezra tried to understand how the other party was viewing a particular situation, what were their fears and goals, and why they did what they did."

A workaholic who had a little office set up in his rehabilitation nursing facility after a knee surgery a few years ago, Vogel underwent hip-replacement surgery in January last year, right after his last trip to China. But nothing was able to slow him down, nothing but death.

Four days before Vogel's passing, Ikels chatted with her husband on the phone. Vogel was still considering joining a Zoom meeting with a Chinese minister but decided to drop the idea due to his condition. The couple talked again the next morning on Thursday. "I had no idea that he would be going into the ICU that afternoon, where he was heavily sedated as his organs began to fail," Ikels said. "There was no bye-bye."

"He was very engaged at the very end of his life," Ikels continued, referring to a planned online session between Vogel and his Hawaii-based Chinese-language instructor one day before his passing, "always getting himself prepared for the telling of another story".

She also recalled those shared nights, when she and Vogel were both preoccupied with research in their separate studies.

"We would take a break somewhere between 9 and 10 o'clock at night. Together, we would sit on the couch and each have a chocolate. He was the one who was in charge of chocolate selection. ... Now I am inundated with chocolates."

In his 30s, as a rising scholar, Vogel was one of 10 academics who penned a 1968 memorandum on China policy addressed to the incoming Richard Nixon administration. Calling on Washington to explore "confidential, even deniable conversations" with leaders in Beijing, the memo was later delivered to Nixon by Henry Kissinger.

In one of his very last emails to Szonyi, Vogel talked about a document he was working on for the Biden administration, making suggestions about how to improve the US-China relationship.

"I don't know if they'll listen," Vogel wrote. "But I'll try."