ART AS CHRONICLER, COUNSELOR & CONSOLER

The second edition of a cultural festival in Xiamen, Fujian province, puts untrained actors and dancers at center stage.

Against a pitch-black backdrop and a mesmerizing song about self-expression, a woman begins to tell her story to another, revealing that she has been pregnant five times but has given birth just twice. The narration is conveyed in a light manner, but without making light of the matter at hand. Rearing two boys, the couple could not afford to raise more children, and the woman's other three pregnancies were aborted.

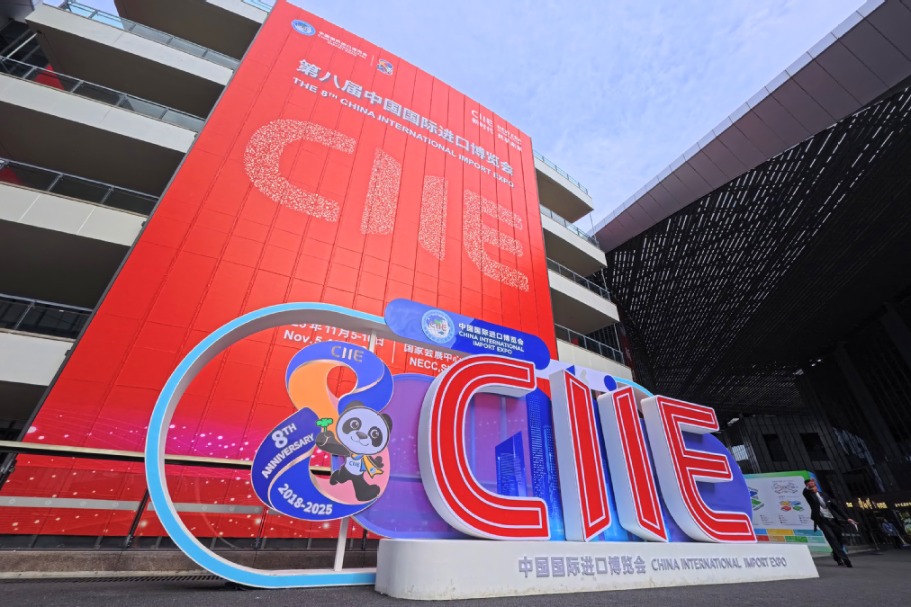

This heart-wrenching tale is based on the woman's real-life experience, adapted into The Story of Giving Birth, a play screened online in the second edition of the Luminous Festival just finished. The festival aims to provide an artistic platform for minority groups and others whose voices often go unheard. Because of the pandemic, events in this year's festival were staged both online and offline, most of the latter in Xiamen, Fujian province.

The Story of Giving Birth tells of the predicament that pregnant women can face, including terminating a pregnancy, giving birth in the roughest of environments and eventually raising children-every one of these made all the harder because of an absence of paternal support.

The play is performed mainly by female migrant workers from the Mulan Community Service Center, a nonprofit social service organization that brings together women who come from all over China to work in Beijing.

The director of the play, Zhao Zhiyong, a professor at the Central Academy of Drama, calls the play a project of applied theater, which does not see drama as art to be appreciated but as a means of serving practical social goals, such as offering school students psychological counseling.

Zhao has worked with Mulan Community Service Center since 2014, teaching the migrant workers to engage in drama as a way of expressing themselves.

Qi Lixia, founder of the center, says the play is the product of a casual discussion in the community in which she talked about childbirth. It turned out that many of the women had been through traumatic experiences that involved great physical and psychological pain.

The experiences were so personal and so painful that the women could not even bring themselves to talk with their husbands about them, depriving them of one channel for catharsis. So Qi suggested to Zhao that they produce a play on the topic.

Over the course of more than a year they interviewed 29 mothers in the community, ranging from 20-year-olds to 60-year-olds, most of whom had followed their husbands to Beijing.

"We then sorted the recordings into a transcript of nearly 300,000 words. As I read them I felt a sense of awe. Their narration of their own childbirth experiences together formed a chronicle of our society over the past few decades."

To tell the stories within a confined space and with a limited budget, the play centers on the experiences of the woman mentioned at the start of this article, who was born in the 1970s and gave birth in the 1990s and in the 2000s, and whose tale is regarded as fairly representative of all the women.

Even though the issue of giving birth is the core of the play, the aim is to say something more generally about the plight of China's migrant workers, of whom there were more than 290 million last year, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Despite the conspicuous absence of men in the play, this is not meant to cast them as villains worthy of condemnation because of their lack of participation in parenthood. Rather, that lack of participation is a by-product of the migrant family's lot: the father needs to continue working, and perhaps far away from his family, so as to support them.

"Prejudice and discrimination toward so-called marginal and disadvantaged groups, including these migrant workers, remain present in our society," Zhao says. "We're keen to use these cultural happenings to communicate with the public, so people learn something about how migrant workers live and how they feel.

"I believe that in this way we can help promote a kind of mutual understanding and empathy between different social groups. Empathy is an extremely scarce and valuable resource. We hope people will be able to understand those who are different from us and the situations they're in."

The second edition of the Luminous Festival, highlighting inclusive arts, also included works from other countries, including Franchir la Nuit and Gala from France, Schweigen Impossible from Germany and Artificial Things from the United Kingdom.

Franchir La Nuit looks at the subject of exile, focusing on childhoods broken by displacement, with a flooded stage and the movements on it representing the numerous transitions they face.

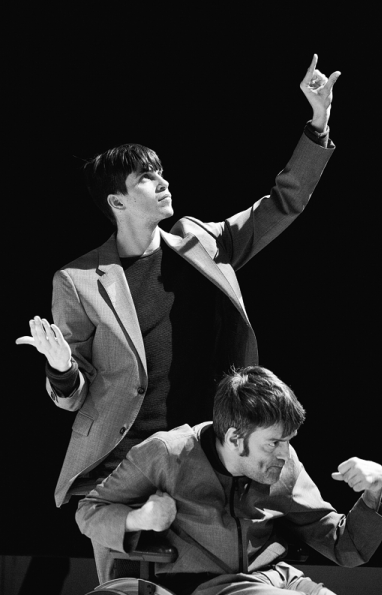

A rendering of Gala, the 2015 award-winning dance by the choreographer Jerome Bel, was staged in Xiamen.

On a board placed on the stage is the Chinese word for ballet. Performers come onto the stage one by one, each performing a pirouette, followed by similar performances of diverse dance styles such as waltz and Michael Jackson, before the dancers come together to perform as a group.

With this unconventional dance performance Bel rejects the traditional standard of "good dancers" and invites people, amateurs and professionals alike, to together perform a dance and create a space of inclusiveness.

"I think dance belongs to everyone, not only professional dancers," Bel says."I want the stage to be a place for equality, not for exclusivity. Everyone has to be represented, not just powerful people."

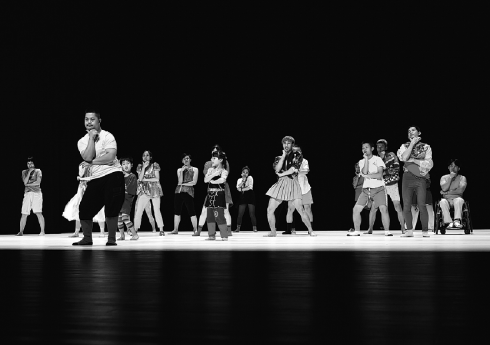

In the Xiamen version the dancers were 20 Xiamen residents from young to old and from many walks of life.

They included Huang Eryan, a nurse in Xiamen who spent six weeks in Wuhan, Hubei province, during the coronavirus outbreak early this year.

"Because of my work I'm usually quite a reserved person in the hospital," Huang says. "We tend to repress our emotions. But taking part in the dance I felt the environment was very open. There was no right or wrong, and we were allowed to be ourselves and encouraged to let ourselves go. So the whole experience was very uplifting.

"I was with the other performers for only a few days, but I feel we developed a very powerful team spirit. It was similar to what happened in our medical team in Wuhan: small but powerful. There was something I could learn from each and every person."

She had little dance experience, she says, and was anxious at first, so was encouraged to just to be herself.

"Most people imagine they are not good enough to dance on a stage, and that's exactly the people I want to cast for Gala-those who think they're no good," Bel says.

"I'm not there to judge the dancing. I'm more interested in understanding what it means and what the dancer is expressing. So Gala particularly welcomes those who say 'I can't dance.'"

Instead of conforming to the traditional power relationship in which the director is free to audition and select the dancers, Bel extends invitations to those within his personal networks.

For a performance that is established on the core concept of "anyone can do it", he feels this is better than holding rehearsals that result in most of the candidates being rejected.

As a result of eschewing flying to protect the environment as well as the pandemic, Bel and his team forewent the opportunity to travel to China for the production, instead holding lessons and rehearsals using video conferencing tools.

Gala is an ideal presentation of human unity, says Ge Huichao, founder and curator of the festival.

"In the performance you can see performers of diverse age groups, backgrounds and identities, a perfect rendering of inclusiveness."

The festival also featured Body Nomadic, a dance project produced by Ge that has an ethos similar to that of Gala-that dance should be an inclusive experience.

As its name implies, the project brought together choreographers, composers, dancers and video artists to conduct workshops within different art, culture and folk communities in Xiamen, re-imagining the ideas of themselves, others and urban living, via contact improvisation, an approach to dance that emphasizes spontaneity.

Participants included children, teenagers, teachers, volunteers, villagers and disabled people from charity and cultural organizations all over Xiamen.

After six workshops at diverse locations, a final community co-creation performance brought participants from different communities together that was livestreamed on Aug 8.

Inclusiveness is about bringing people together, Ge says.

"We must change the prevailing way of cognition, via art or popularization of new concepts. It's very important that we no longer condescend to people with needs, taking for granted that they require our help. Everybody in some ways has deficiencies of their own, some visible and others not.

"Inclusiveness means not to label others, define them or objectify them. It means to return to the origin of equality, to see yourself and others through the innermost being."

Today's Top News

- China's consumer prices creep up in October

- Fresh opportunities seen in China

- Xi meets IOC chief and its honorary president

- National Games an embodiment of China's strength, unity and progress

- Xi declares 15th National Games open

- Xi attends opening ceremony of 15th National Games