Wise to keep a distance from 'the most warlike nation in history'

Much has been written recently about so-called China's "Wolf Warrior" diplomacy. Western-based commentators have widely criticized what they see as a more assertive, some say, bullying stance taken by a number of Chinese foreign affairs specialists including diplomats based around the globe, who are actually often on the defense.

As it happens, we can apply the same sort of assertiveness-metric to foreign affairs management in the West. It is profitable to consider the US and Australia and, briefly, New Zealand.

The clear dominance of American military, economic and political power after WW II provided the means for the US to oversee an era of extended peace – and also to shape transnational outcomes in America's own interest to a remarkable extent. Soft power, a term coined by Joseph Nye in 1990, has been defined as "[T]he ability to affect others by attraction and persuasion rather than through the hard power of coercion and payment." More recently, certain US commentators have critically analyzed what they call China's sharp power.

In fact, the US has deployed all three powers, soft, sharp and hard, for many decades. In 1985, a respected American analyst, George Scialabba, noted that certain regimes following policies considered unacceptable to the US were "subjected to American hostility, subversion or even invasion", adding that, "rhetoric aside, promoting democracy, self-determination and human rights has little to do with American foreign policy."

More recently, Dan Sanchez, argued, after reviewing the remarkable careers of the brothers, John Foster Dulles (US Secretary of State, 1953–59) and Allen Dulles (CIA Director, 1953–61), that together they created a legacy, for the US, of perpetual war.

Building on this potent tradition, Washington has, under the current Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, developed a divergent, conspicuously muscular form of power-diplomacy. In some cases, as with Iran, it can take the form of violent coercion. In the case of China, the US is now firmly committed to a win-lose Sino-strategy: for the US to win, China needs to lose.

Very recently, US political power has been starkly deployed (domestically and internationally) in response to China's plan to enact a plainly required, new national security regime for the HKSAR. Yet another audaciously meddling law was recently passed in the US Senate and House of Representatives, shortly after Secretary Pompeo declared that, "No reasonable person can assert today that Hong Kong maintains a high degree of autonomy from China". Presumptuous sanctions of various sorts were threatened. The assumed right to interfere is unconcealed.

In mid-April, meanwhile, Mr Pompeo stipulated that Beijing should grant the US access to a Wuhan laboratory: "We are still asking the Chinese Communist Party to allow experts to get into the virology lab so we can determine precisely where this virus began." The essence of this megaphone approach is to say: we presume you are guilty, unless you can prove otherwise; and we decide if you have done so. There are closer resonances here with the Spanish Inquisition than with Common Law presumption of innocence principles.

And what of Australia?

Most striking is the recent Australian decision to badger China on the need for an investigation - conducted independently of the WHO - into the COVID-19 virus origins. This proposal came across as measurably associated with the ill-tempered American, Wuhan-focused, inquisitorial demands, which were designed to further incite a blame-China narrative within US domestic politics.

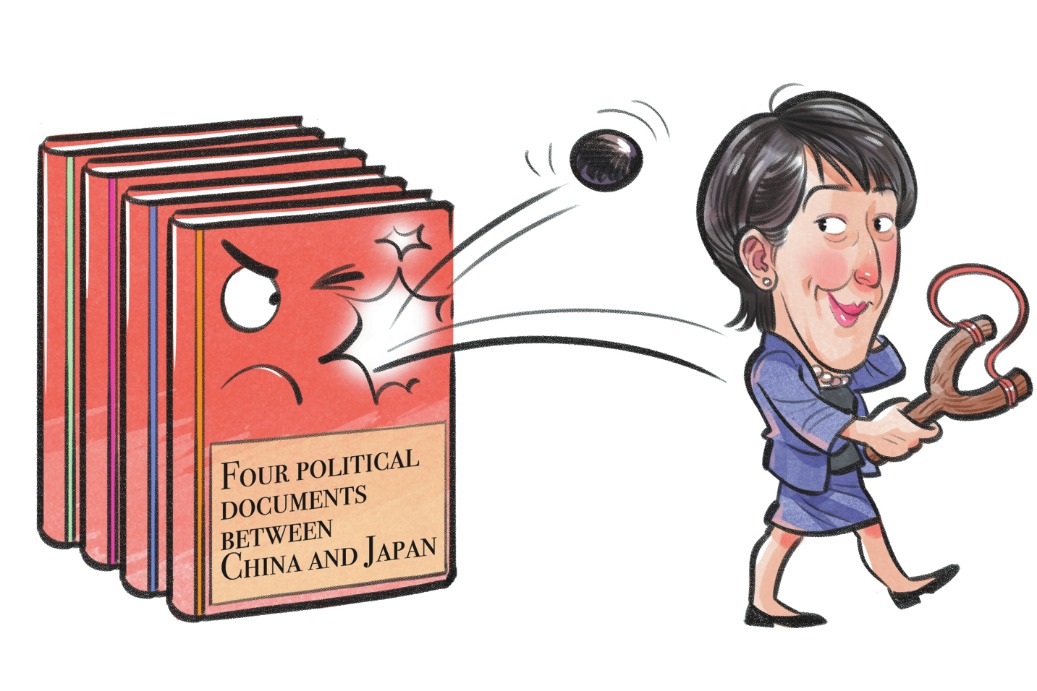

A respected, previous Australian Foreign Minister, Gareth Evans, recently observed that, "[T]he signs of strident Sinophobia [in Australia] are now everywhere to be seen [including in] the government's ill-thought rush to single out China for international blame over COVID-19 [and in] Foreign Minister Marise Payne's ever more unbalanced statements."

Further acute observations were offered by a former Australian Ambassador to China, Geoff Raby, in June. He noted that, "There are some people [in Australia] in the media, in think tanks….who see a bad relationship with China as a badge of honor" adding that, "what is particularly pernicious is that commentators and even politicians are weaponizing the relationship and delegitimizing economic interests."

Australia has tended to cast itself as a victim as this quarrel has developed. It considers that it has been getting a taste of undeserved, Wolf Warrior pressure from China related, for example, to certain exports, tourism and onshore international education. How apt, though, is this viewpoint?

When Beijing issued warnings to Chinese tourists and students to be alert to increased race-based risks in Australia Marise Payne accused China of spreading disinformation about the danger of racist attacks in Australia. Awkwardly, hundreds of race-targeted attacks against Chinese people have been widely reported in the Australia media, some of which have involved actual violence. There has also been cross-party condemnation, in the parliament, of increased anti-Asian racism in Australia. These problems have intensified with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a harmful signaling-impact, too, arising from the government's misguided, forceful reproaches: those launching abuse feel more empowered to do so within the context of the repeated, conspicuous government disputation directed at Beijing.

Interestingly, as Washington was ramping up its calls for a COVID inquisition, New Zealand made it quite clear it was not interested in joining any sort of "witch hunt" over the COVID crisis. Indeed the New Zealand Prime Minister noted, in mid-May, that New Zealand had learned from other countries, including China, adding that China was, "obviously the first to use lockdown and I think that has saved lives globally".

Australia has, more recently, made much of perceived Chinese threats to its national security. But, as Geoff Raby suggests, seriously undermining Australia's bilateral economic ties with China presents a fast-track route to jeopardizing Australia's national security. Without economic security, national security is made far more vulnerable.

Australia has the most China-dependent economy in the developed world and it has benefitted hugely from this. From 1991 to 2019, Australia experienced 28 years of uninterrupted growth – a record in the OECD. China has played a pivotal role in this achievement. China was also crucial in helping Australia to maintain growth during the Global Financial Crisis around a decade ago, an achievement matched by few others.

How then has Australia careened into this spasm of Sino-confrontation? The reasons are complex and include a depressing lack of reflective (New Zealand style) impulse control combined with local political opportunism. Gareth Evans has, though, put his finger on what may be the pivotal explanatory factor. He argues that excessive deference is being paid by both government and opposition to "the national security and intelligence community, now itself more collectively deferential to Washington (notwithstanding its catastrophically dysfunctional current leadership) than I can ever remember."

Like Hong Kong, Australia has a huge vested (win-win) interest in seeing the rise of China maintained and enhanced. Late last year I wrote that China, as an extraordinary advancing power within the Asia-Pacific, clearly raises distinctive challenges for Australia's foreign policy posture. These need to be managed, firmly and carefully in Canberra.

Still, China does not, I said, purposefully threaten Australian in any serious way. An anxiously forceful US, on the other hand does threaten Australia at a measurably more significant level: first, by hectoring diplomacy, encouraging intensified antipathy towards the trading partner who has done more to help remake Australian prosperity in the last thirty years than any other country; and secondly, due to the serious hazard of being drawn into yet more US military adventures – possibly involving certain levels of forceful confrontation with China. This is not an imaginary risk: the former US President, Jimmy Carter, reminded us, in 2019, that America is, "the most warlike nation in the history of the world". It was the principal combatant in five major wars since WW-II.

I argued last year that, examined rationally, the strategic position for Australia was very clear - but foolish decisions, influenced by the US, might still be made in Canberra. It gives me scant pleasure, now, to say that my earlier concern has been substantially confirmed.

The author is a visiting professor in the Faculty of Law, Hong Kong University.