Doctors perform spinal surgery on unborn baby

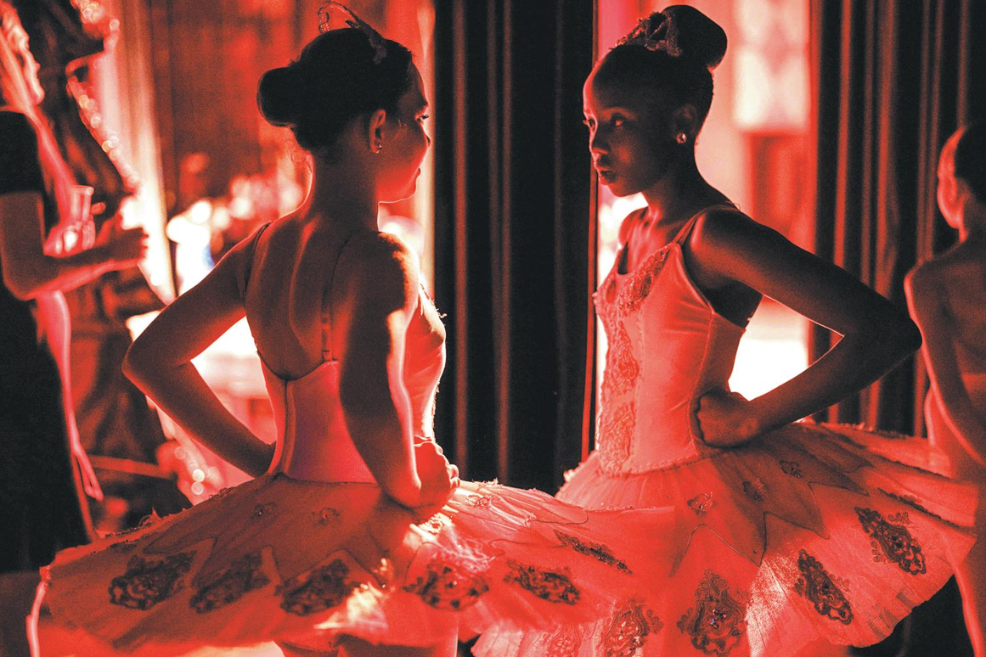

Radical procedure provides new options for fetuses diagnosed with debilitating spina bifida

Doctors in Britain have successfully performed an operation on an unborn baby with spina bifida in a groundbreaking procedure that involved removing the fetus from the womb and replacing it following surgery.

The pioneering procedure provides a new treatment option for fetuses diagnosed with the condition, including those in parts of China where it is prevalent.

Spina bifida hinders normal development of the spine and spinal cord, and, in severe cases, leads to incontinence and the total paralysis of the legs.

Bethan Simpson, a 26-year-old nurse from Burnham, England, elected to move forward with the surgery after scans revealed her baby girl’s condition.

The surgery was performed last month at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London by a team of specialists from University College London Hospital and University Hospitals Leuven in Belgium.

The operation required the temporary removal of the baby from the uterus, according to Simpson.

“They took her out of my womb and popped her straight back in to stay there as long as she can,” Simpson wrote on social media.

Her baby, which is due in March, is recovering well. Simpson said she wanted to share her story to raise awareness among parents in similar situations.

“It’s not a death sentence,” she said. “Yes, there are risks of things going wrong, but please think more about spina bifida. It’s not what it used to be.”

It is just the fourth time such a procedure has been successfully carried out in the United Kingdom.

Surgeons at Great Ormond Street conducted two similar operations on fetuses with spina bifida last year, though in those cases the babies were left in the womb during surgery.

Paolo De Coppi of the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health said that performing prenatal surgery – rather than operating on infants with spina bifida – is advantageous for two main reasons. The surgery greatly reduces the need for the insertion of a surgical shunt following birth, and the newborns can expect significant improvements in motor function as they develop.

Shunts are often necessary to relieve pressure on the brain, however they can affect both mobility and brain function, so avoiding their use is preferable, according to De Coppi.

Spina bifida is associated with poor life expectancy, and high levels of mortality in infants aged five and under.

In many cases when spina bifida is detected prior to birth, parents elect to terminate the pregnancy. The United States Centers for Disease Control found that between 1990 and 2012, 63 percent of pregnant women in North America and Europe chose to terminate their pregnancies when a spina bifida diagnosis was confirmed.

Simpson said she and her husband Kieron were initially presented with two options – to terminate, or continue with the pregnancy.

However, one of her nurses scheduled an appointment with a specialist in London, where Simpson learned of the prenatal surgical procedure.

“We had to do it,” she said. “We also had to meet some seriously strict criteria. Me and baby went through amniocentesis and MRI and relentless scans. We got approved and, on Dec 17, we planned for surgery. Our lives were such a rollercoaster for the next few weeks.”

The high prevalence of spina bifida in parts of China, some Latin American countries, and among indigenous communities in Canada and Australia, suggests that rates of the condition differ among ethnic groups. In the United States, rates are highest among Hispanics and whites, with lower levels in the black population.

Three provinces in China – Shanxi, Hunan and Hubei – have particularly high rates of spina bifida. A Peking University study of four counties in Shanxi province found spina bifida present in 58 out of 10,000 newborns. The Centers for Disease Control estimates the global average is around two in 10,000 newborns.

Genetic, environmental and dietary factors have all been linked to the disease. To reduce the risk, expectant mothers are encouraged to take supplements of folic acid, which is a synthesized form of vitamin B9.

In the 1990s an epidemiological study of 250,000 pregnancies in China confirmed that sufficient levels of folic acid greatly reduce the risk of spina bifida and other neural tube defects.

This study, and others, led the US to mandate the fortification of wheat flour with folic acid, something that started in 1998.

The prevalence of fetal neural tube defects in the US has since dropped by 30 percent. Canada followed suit in 2000, leading to a halving of the number of such defects in newborns.

Around 80 countries now mandate that certain foods should be fortified with folic acid. The British government has debated a mandate several times during the last two decades, though no legislation has yet been passed.

Some British politicians argue that a mandate constitutes government overreach. Others have pointed to studies that purport a correlation between folic acid supplements and bowel cancer, as well as the masking of vitamin deficiencies in the elderly.

But the UK looks to be nearing a law. Health Minister Steve Brine announced that this year the government will conduct a consultation into the mandatory fortification of wheat flour with folic acid.

“We have been listening closely to experts, health charities and medical professionals and we have agreed that now is the right time to explore whether fortification in flour is the right approach for the UK,” said Brine. “My priority is to make sure that, if introduced, we are certain it is safe and beneficial for all.”

Nigel Dodds, a member of Parliament for the Democratic Unionist Party, welcomed the news. His son, Andrew, died at age eight from complications due to spina bifida and hydrocephalus.

“We would love to see children being born without having these conditions,” said Dodds. “We just have to move on with this issue, there is no good reason not to.”