Nomads shatter assumptions about enterprise

China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

Nomads shatter assumptions about enterprise

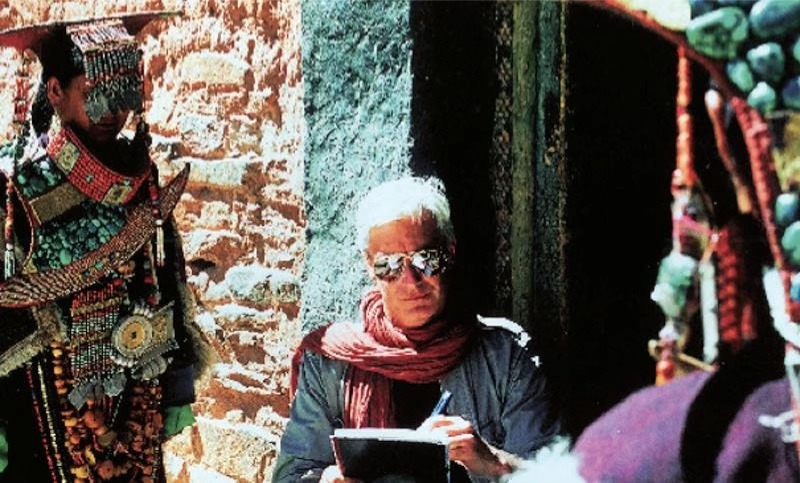

Editor's note: Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation's journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is running a series of articles every Thursday starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Starting this month, China Daily will run two articles from this series each week – on Tuesday and Thursday. Keep track of the story by following us.

2002: As the weeks unraveled, our Searching for Shangri-La documentary film team traveled from Tibet to Qinghai, a Chinese province once referred to as Eastern Tibet. A vast expanse of green steppes and sharp ice-capped mountains, it was home to Muslim traders and Tibetan nomads who lived alongside each other. As the road wound into higher altitudes, we saw fewer villages and the vast landscape became dotted with herds of sheep and nomad tents made of black yak felt. Every hundred kilometers or so we drove through a "Wild West" town, where Tibetan ranchers in tall cowboy hats and plastic sunglasses rode big motorcycles decorated with prayer scarves and auspicious Tibetan symbols. They spent at least part of their day playing pool up and down the streets, which were often jammed with herds of passing sheep.

Our jeep splashed across icy rivers trickling down from melting glaciers. We drove deeper until there was no road, and then continued across grassland. As we entered the next valley, I noticed a monk in saffron robes across the river, waving. We pulled up to where he sat on a rock, head shaven except for a small mustache and goatee. His smile widened over his goatee, stretching to pointed elf-like ears. "Are you by chance looking for Jigme Jensen's cheese factory?" he asked, giggling. "This is why you came here. You think you are searching for Shangri-La. Actually, you are looking for our cheese factory!"

Over the years of filming and working in Tibet, it became apparent people who live close to the earth have an intuition that far exceeds that of city-dwellers. With our over-reliance on technology, the human ability to intuit has been diminished. Instinct is on its way to becoming extinct. Living close to the earth, Jigme Jensen sensed our arrival, and sent one of his monks to find us.

With a flourish of his hand, the monk offered to lead the way. A snow peak hovered over the crest of mountain above. Eagles flew so close I felt I could touch them. A freezing cold river ran before us. We followed the river, then crossed it, stepping on stones one at a time as there was no bridge.

In contrast to everything around, a tiny factory building stood before us.

Tibetan workers stepped out to greet us. Dou Yan began filming immediately. Then another saffron-robed monk stepped forward. This was Jigme Jensen, head of the yak cheese factory.

I was flabbergasted. A factory so utterly remote, so lacking in logistics, made no sense to my Western-coded business mind. It had taken us days to find the place, so I asked in blunt frustration, "How can you make cheese in a factory away from markets, transport, everything? You are not near anything!"

"We are near the yaks," Jigme explained nonchalantly. "You see, we make yak milk cheese."

A Tibetan woman, chunks of amber strung around her neck and wearing a huge cowboy hat, poured yak butter tea. A white horse nibbled grass nearby. I looked in the cup. This time I did so carefully.

Over the coming days Jigme Jensen would change the way I think about cheese, yak, mountains, people and education. More importantly, he would shatter all of my assumptions as to what constitutes a good business model.

I asked him to show me his factory. It was simple. There were only three large rooms.

Before we entered, Jigme asked me to put on rubber boots and a white lab coat and face mask, as if I was entering an operating room. "We must keep international health standards here when making yak cheese for export." Jigme explained with a flourish of his hand, like he was about to wipe Dutch gouda off the market.

Sure enough, entering the little Tibetan factory was like stepping into a cheese factory in the suburbs of Amsterdam. The same techniques were applied. Yak milk was churned into heated vats and settled into molds. It solidified on wooden racks in cool rooms. I was convinced. Jigme Jensen was making real cheese.

Only one question remained. "Why here?"

"We need to be close to nomads who bring us fresh yak milk every morning and every evening. They bring it through this door,"Jigme said, pointing to a side door leading to the room with the hot churning vats.

"But you are nowhere near any point of distribution," I replied, volunteering my professional opinion as lawyer and investment advisor. "There are no roads, no points of connection. You are in the middle of nomad country in mountains. If you want to sell your cheese internationally, or even in China, you have to be manufacturing closer to infrastructure and distribution points." Before long I learned such advice was useless, because I did not understand the nature of nomads.

"I don’t worry about distribution," Jigme explained, "because I do not want to manufacture cheese in a place that might be inconvenient for nomads".

It still didn't make sense. "So you are making yak cheese in yak country. How do you get the cheese to market?" He still hadn’t answered my question. "Does it make any commercial sense to build a factory here, just to provide convenience to nomads making yak milk deliveries?"

"But that is just the point," Jigme insisted. "You see, they all live in mountains, in yak felt tents at high altitudes. They cannot leave valleys so easily. So by having the factory here in the mountains, they can deliver yak milk every day, even twice a day. In this way the milk is assured to be fresh."

I still did not understand this. "You can raise yak on farms near a factory near a city or point of distribution, right?"

"Wrong. It would not be wild yak milk," Jigme sighed. "That is, milk from yaks herded by nomads. My real purpose is to help nomads".

Now I understood what was driving Jigme.

Jigme explained the nomads, being herdsmen, traditionally had no income. Now with economic changes occurring everywhere, they need cash to buy goods. By purchasing yak milk every day Jigme was providing an income without affecting their traditional lifestyle. He was not changing their traditional means of livelihood, but supporting and strengthening it.

Jigme's response is to reinvest cheese profits into building schools. He pointed in the direction of another valley. "Tomorrow I will go to that valley to determine plot lines for walls of a new school. It will be built with proceeds from yak milk cheese!" By bringing enterprise and education to the nomads Jigme was offering their communities an advanced approach to sustainable development; one both supportive of and relevant to their livelihood.

That said, Jigme still had to overcome the logistical challenge of distributing cheese from his isolated factory. Every day he would fill up a Jeep with round cheese blocks, driving through rivers and mountain mud to Maduo. The Tibetan town of teahouses and beer halls looked like a scene from High Noon.

At Maduo, monks from Jigme's monastery would load the yak cheese onto trucks and vans, to haul it over a winding road for the 15-hour journey to Xining, Qinghai’s main city. From there it would be shipped to Beijing and other cities of China, as well as Europe and North America, where yak cheese was the ultimate item for chic cocktail parties and wine-tastings.

Meanwhile, Tibetan nomads earned cash and kept their traditional lifestyle.

Jigme explained since establishing the cheese factory, nomad income in the surrounding valleys and mountains had increased, reinforcing rather than disrupting their traditional lifestyle. In Jigme's mind, preserving nomad life had impact far beyond maintaining traditions. He saw nomad existence as integral to survival of a delicate, endangered and diverse biosphere.

Yak grazing patterns, tens of thousands of years old, are essential to the balance of nature in this area. The biodiversity, permafrost and glacial cycles of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, account for the source of water from down glacial river flows, for China, South Asia and mainland Southeast Asia.

Please click here to read previous articles.