Seeking inner peace

As millennials tire of city life, the ways of the humble hermit become increasingly popular

"I have sat here quietly and let my brush fly/Suddenly this volume is full," the ninth-century poet Han Shan (寒山) once wrote, when asked to describe what he found interesting about life on Cold Mountain, the jagged peak from which he took his name.

For many young people, living in the iron-and-concrete skyscrapers that dominate China's newly developed cities, the view from the rugged mountaintop can seem far more attractive than the smoggy skies and crowded roads of their daily routine. The urge to "to be free of all this/against all the world, choose simplicity," as wilderness poet Xie Lingyun (谢灵运) described after his exile from the capital in 422, is a common one.

| Going back to nature, to a life of simplicity, free from the din of materialism, is an attractive proposition for some people. |

Going back to nature, to a life of simplicity, free from the din of materialism - it's an attractive proposition. In part that's because, for all its revered roots in tradition, the hermit life is one that blissfully rejects everything Chinese society now holds dear: family, property, career, connectivity.

In the information age, to cut oneself off entirely is an actively transgressive choice - but one that some are more than happy to make.

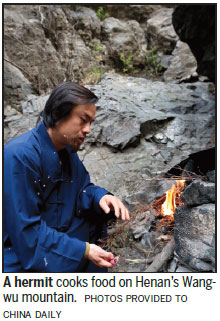

Shen Lixing, a cab driver from Zhengzhou, is among the several dozen who have traded a city apartment for a small cell on Wangwu, a mountain in Henan province that's been imbued with spiritual symbolism since China's legendary Yellow Emperor supposedly built the first altars on its summit.

In her previous occupation, Shen told Xinhua, she was "selfish, bad-tempered and greedy", but life on Wangwu has given her a calming new perspective. Shen has a television and mobile phone, and checks the news daily, but others on Wangwu shun even these small luxuries, passing their time solely with introspective activities like calligraphy, hiking or meditation at one of the mountain's Taoist temples.

Taoism is strongly associated with hermits in China because of its emphasis on harmony with nature's rhythms.

US writer, translator and former monk Bill Porter, who calls himself "Red Pine" (赤松) in Chinese after the Taoist immortal, tracked down several hermits who'd survived unmolested in the Zhongnan mountainous region of southern Shaanxi, publishing his findings in Secluded Orchids in a Deserted Valley (《空谷幽兰:寻访当代中国隐士》) in 2001. The book, known as Road to Heaven: Encounters with Chinese Hermits in English editions, sold only a few thousand copies initially, but after it was republished in 2009, it became a sudden bestseller in China. Porter's book provoked a spike of interest in a way of life many had assumed was long gone.

To some, Porter's book was proof of the saying "The wise live on the mountains" (智者隐于山, zhìzhě yǐn yú shān), and the peaceful peaks of Zhongnan were soon bustling with aspirational ascetics and wannabe wise men. Some built their own shelters, wearing linen, practicing calligraphy and keeping their hair long.

However, not everyone who builds a hut becomes a hermit. Zhang Jianfeng, whose own book on Zhongnan's mountain men was directly inspired by Porter, has seen plenty of tourists come and go.

"The arrival of the winter drives those pseudo-hermits back to the cities because the cold is extremely tough," he observed. Others develop signs of mental illness, mumbling to unseen persons, seemingly driven crazy by the solitude.

Although much of this "hermit tourism" was inevitably short-lived and rather fanciful in nature, a few were inspired to go the distance. Some, such as Zhou Yu, editor of the lifestyle magazine Wendao ("Seeking Way"), which celebrates traditional culture, tried to physically retrace Porter's footsteps. Several years ago, he trekked through the valleys and hill paths where Laozi, the mythical founder of Taoism, once roamed, in search of the sage's modern equivalent.

Zhou found his Laozi in Ming, a cottage-dwelling ascetic who settled on the mountain after leaving a troubled home at 17, first roaming the country in search of answers, traveling through Fujian, Guangdong, Jiangxi and Hubei with only a chipped mug for company, before finally settling on Zhongnan. There, he pursues an existence at once traditional - reading sutras, tending to the cottage - and unconventional - owning a motorbike and sometimes sharing his lonely quarters with a hermit girlfriend.

After several months living with Ming, Zhou published Deep in the Clouds (《白云深处》) in 2011 about the experience, describing Ming's hermitage as "a place where he can live a life in which he can face disputes peacefully" and pinning much of modern society's anxiety on having "too much information ... and (not) dealing with it properly." On the mountaintop, "you have time to think". Nowadays, Wendao magazine offers weeklong "ascetic trips" for those who don't need too much time.

A typical day begins at dawn with gardening, pulling weeds, planting herbs and vegetables, chores around the house with tea at noon, and ends with a simple dinner, then a postprandial walk followed by meditation before sunset, when, in the words of Han Shan, "soft grass serves as a mattress/my quilt is the dark blue sky/a boulder makes a fine pillow".

Worse than hardship are the dangers, which can sometimes be extreme: in winter, temperatures drop below -20 C, and every year there are reports of amateur adventurers freezing to death on Zhongnan. Even foraging for food can be lethal - the area is home to deadly snakes, as well as poisonous fruit and fungi. But that hasn't stopped newcomers from moving to the mountain.

"Twenty years ago, there were just a few hundred people (here) but in the past few years, the number has increased very quickly," one part-time hermit said.

There are now hundreds of small dwellings on Zhongnan, and, by some estimates, between 3,000 to 5,000 hermits are dotted around its peak. Half are women, and most live without electricity, heating, or meat, subsisting on roots, herbs and vegetables. When they trek farther up the mountain for contemplation, journeys that can take several weeks, their diet can be little more than pine leaves and dew.

Those drawn to the mountain path can include graduates seeking enlightenment on the career path, well-educated professionals and people jaded with modern life. Some have read Porter's book or articles in Wendao, or seen one of the documentaries about hermit life, such as 2005's acclaimed Amongst White Clouds, directed by an American student who'd discovered Buddhism through reading Porter.

"When I lived in the city, I partied all the time," one of Ellen Xu's subjects recalls in her short film about millenial hermits, Summoning the Recluse, describing a typical social treadmill of restaurant, KTV bars and card games. "You recycle the same routine every day." By contrast, his new life was "unconstrained", "simpler", with "fewer desires". While some of his fellow hermits announced their intention to stay indefinitely, another emphasized, "I won't spend the rest of my life here; that's for sure."

Mountain life may not suit everyone wishing to escape the city or society, but nor is it the only option. Some prefer the comparative comforts of a vacation. For others, it's a simple matter of leaving the city or downsizing. Scholars have argued over the "right" way to live alone for centuries. For the truly enlightened, there is no single path. As Wendao's Zhou Yu said: "Get to know your needs and desires, and find a proper position. … If you can do that, you can find peace and quiet even if you live in the city."

Courtesy of The World of Chinese; www.theworldofchinese.com.cn

The World of Chinese

(China Daily Africa Weekly 10/20/2017 page23)

Today's Top News

- EU has much to learn from China-Global South ties

- Xi holds phone conversation with Merz

- Xi stresses high-quality cultural-ethical advancement

- Trump halts Harvard's intl student enrollment

- Xi's visit gives impetus to our work

- Financing support enhanced for micro, small companies