Heart of emperor at home in south

When Emperor Qianlong arrived in Hangzhou for the first time in 1751 at the end of a journey lasting as long as four months, he was already 40. The visit heralded the start of a relationship with the city that would play an important role in the second half of his life.

In fact, over the next 33 years Qianlong would undertake the 1,500-kilometer journey from Beijing six times. These days, when one can be blase about having breakfast in Beijing and dinner in Berlin the same day, it is easy to underestimate the emperor's undertaking. Given the logistics and physical rigors of such a journey-he was 73 when he made the last one-it is clear that Hangzhou was a special place for him, the longest-living-and reigning - emperor of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), China's last under feudalism.

The trips Qianlong made in those 36 years are known today as the "Journeys to Jiangnan". The term Jiangnan means south of the Yangtze River and refers to large tracts of land covering what are now Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. Jiangnan was China's hothouse, culturally and commercially, with its talented people filling the cabinet and paying taxes into the royal coffers.

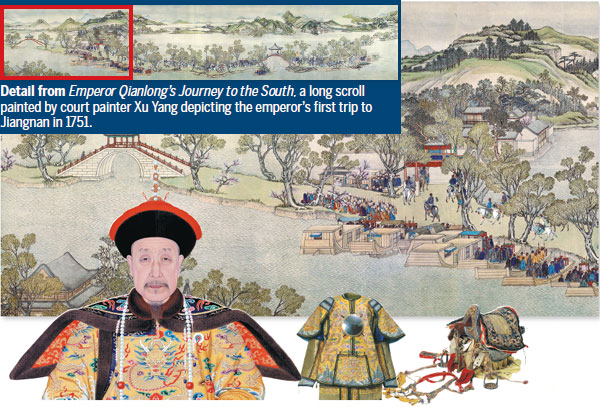

| From left: Emperor Qianlong; his ceremonial garments; his saddle. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Hangzhou (also known as Lin'an when it served as the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty between 1129 and 1279), boasts superb natural scenery and a strong literary tradition. It was the best Jiangnan had to offer. On every "journey to the south", Emperor Qianlong stopped in Hangzhou. In fact, five times Hangzhou was his southernmost point before his return.

"Nowhere else beckoned him in the same way that Hangzhou did," says Ma Shengnan of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Ma is the curator of an exhibition now showing at the Zhejiang Museum in Hangzhou. Entitled Ruler of a Golden Age, it seeks to re-establish the link between the emperor and the city he loved through more than 200 objects ranging from beautifully crafted jade, porcelain and lacquer ware to works of art and calligraphy he commissioned or produced himself.

"We intend to do justice to him," Ma said. "While trying to find time to play his other roles, including the country's No 1 cultural patron and art collector, Qianlong was first and foremost a ruler with a strong sense of his own royal duties."

And when it came to Hangzhou, a city by the Qiantang River, fulfilling royal duties meant pushing forward and monitoring the building of levees.

"The Qiantang River, running for more than 500 kilometers before disgorging into the East China Sea, was Hangzhou's biggest natural threat until late in the country's contemporary history," Ma says. "Bearing in mind that Hangzhou and its surrounding regions were the empire's crucial source of tax revenue, keeping the destructive waters at bay was the emperor's top priority."

According to Le Qiaoqiao of the Zhejiang Museum, who is also behind the exhibition, the emperor aroused debate in his court as to the type of levees to be built.

"The choice was between wood and stone. The first were cheaper and relatively easy to build; the second were stronger and could be expected to last longer. Most court officials opted for the wooden ones, arguing that Hangzhou, so far from Beijing, the imperial capital, would pose no serious threat to social stability even in case of a flood. The matter also became entangled - as such matters invariably did - in court politics.

"However, the emperor stood firmly behind the second option and the decision was made to build extended stone levees during his fifth visit. That decision proved to be the correct one, with no serious flood occurring after the levees were completed, and only small-scale repairs being required in ensuing years."

It is also worth noting that one of the emperor's most important appointees was an official named Zhu Shi. Zhu made his way into the emperor's service by taking a test presided over by Qianlong himself during one of his early trips to Hangzhou. The examinees were required to answer a question about the levees.

The levees were made of stone blocks piled up neatly, one layer upon another, and vividly dubbed "the fish-scale levees". Parts of the structures still remain, reminding us of the emperor whose multiple journeys to Jiangnan are often viewed as mere pleasure trips.

Of course, there was an element of fun in the journeys, which the emperor didn't deny. Being a prolific poet, Qianlong wasted no chance to record his thoughts and delights on his travels. The Palace Museum now houses 53,000 pages of the emperor's draft poems, with more than 20,000 pages discovered in 2014.

On view at the exhibition are two pages of writing entitled Five Poems on Eight Sights Along West Lake, which Qianlong wrote in 1784, during his sixth and final visit to Hangzhou.

The value of the two pages, Ma says, is in the fact that they were drafts, and therefore faithfully reflect, at least in part, the author's thought processes.

"Another thing is that, rather than leaving his works open to interpretation, the emperor insisted on getting his true thoughts through. What he did was to fill the space between lines with explanatory notes. It's like saying: 'This is what I intend to say. Don't get me wrong.' The emperor was certainly not one to appreciate abstruse beauty."

The "eight sights" were all from the emperor's palace in Hangzhou, built in 1750, one year before his first visit. As a man of means, Qianlong extended his passion for the beauty around him easily from page to reality once he returned to Beijing. The construction of temples, minipalaces and bridges took place in Yuquan Mountain in the capital's western suburbs, conjuring up a view similar to the one Qianlong encountered in Hangzhou's Shengyin Temple.

But nothing was more telling than the retirement garden Qianlong built for himself inside his grand royal palace in Beijing - the Forbidden City. The garden, in the northeastern corner of the complex, was completed in 1776 and features buildings with sophisticated interior design, clearly influenced by the Jiangnan style.

Yet Qianlong never spent a single day in his garden of retreat. Officially handing over the crown to his son, Emperor Jiaqing, in 1795, he stayed in the center of power for four more years, until his death in 1799.

During Qianlong's last visit to Hangzhou in 1784, near the end of his final trip to Jiangnan, he turned 73. The emperor, who prided himself on his many military achievements, inspected his Manchu troops stationed in Hangzhou. (The Qing rulers were of Manchu origin, a horse-mounted minority group from northeastern China.)

"Zhejiang was one of the few places where the Qing court trained its navy," Le says. "But the Manchu soldiers, having been pampered for so long thanks to their special status, had long been disconnected from their horseback tradition."

According to the record, during that inspection some Manchu soldiers, despite their eagerness to impress the emperor, failed disastrously in archery.

"The deeply disappointed emperor, who watched the show with his son, the future emperor, even left poems expressing his sadness," Le said.

By that time it may have been too early for the powerful emperor to sense any real crisis. But if he did, he was proved right, again. The empire after his death was shaken by internal revolts. Pressure from the outside was also mounting. The door of the empire, closed since the 14th century, was about to be forced open by Western powers.

Today the emperor is often blamed for his vanity and extravagant lifestyle, partly evidenced by the royal journeys he made, a charge he would no doubt have countered vociferously, given the chance.

"People talked about these journeys, imagining up all the romances that could have happened, without ever mentioning the royal duties he performed," Le said.

"Over history, especially over the past 30 years as popular period dramas on television have become a major channel for young people to become acquainted with historic figures, Qianlong has emerged, from time to time, as a hedonist and a lady killer. This exhibition is about to put that right."

However, this does not mean the six journeys, on top of others Qianlong made to other parts of his empire, should be immune from criticism. In his twilight years, he ordered a carving of a jade seal to commemorate his 10 major military triumphs. The seal is on display in the exhibition. The emperor looked back at his life's journeys in a candid and reflective tone. The words are kept in Qing official documents.

"I have been emperor for a whole 60 years, with few blemishes except for the six journeys to the south," he said, talking to Wu Xiongguang, a confidant.

"They depleted the royal coffers, leaving a burden upon my people. If any future emperor would like to go on similar trips, you must try to stop him. If you don't, you had better not face me in the afterlife."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 09/22/2017 page1)

Today's Top News

- Ukraine crisis a lesson for the West

- Autonomous networks driving the progress of telecom sector

- China launches cargo drone able to haul up to 1.2 tons

- Key role of Sino-German ties stressed

- Tariffs hurt global trade: Experts

- Rescuers race against time to find survivors