Fast & furious

Stress levels are high and competition is fierce between rival couriers in food delivery business

Driver Zhang cuts an impressive figure online. His rating on Ele.me (meaning "Hungry?"), a food-delivery app, is 91, meaning almost all his 1,511 fast-food deliveries were made on time - no mean feat, in light of Beijing's oft-maddening traffic and convoluted building-numbering systems. Zhang's average delivery takes half an hour, from order to arrival. These, along with other statistics, are prominently displayed on his Uber-style profile, a potent status symbol of both Zhang's success and his precarious position.

From down-votes to disagreements, every one of Zhang's customers wields a degree of power over his job. It's worth remembering this when a driver, running late, calls to ask to be registered as having arrived, even when the map shows him still lost, three blocks away. Tardiness comes with consequences, including fines and bad feedback, impacting a driver's overall rating.

| Most couriers that deliver food in China's big cities are young men. They can earn as much as 6,000 yuan per month. Provided to China Daily |

Zhang works for Fengniao (or "Hummingbird"), the patented delivery system developed by online takeout platform Ele.me. With blue uniforms and branded scooters - in contrast to rival Meituan's black-and-yellow livery - Ele.me's drivers can be spotted in the thousands in cities across China, like the vanguard of some moped army. The red-jacketed ranks of search giant Baidu's delivery arm are called "Baidu Knights", and their profiles are decorated with medals such as "gold knight" for outstanding service in the line of duty.

"These couriers are young and hotblooded, many not well educated, and dressed in different uniforms," industry observer Liu Peng told Chinese media outlet Caixin.

Joining a company is like being part of a group, Liu says. "You have your own emblem. If you join Ele.me, you're part of Ele.me. Sometimes they fight," says Liu.

Companies are engaged in fierce competition to deliver food fastest and cheapest. Certainly, delivery companies are hoping for a positive environment to make money - and it's big money. Last year, the food delivery industry as a whole raked in 176 billion yuan, according to estimates by a market research company cited by People's Daily Online, a 361 percent increase over a year earlier. While they specialize in food, anything from sushi to Sichuan cuisine, the bigger apps offer other ingredients for a good night in, from sex toys to morning-after pills.

Market leader Ele.me holds a 34.6 percent market share, with Meituan and Baidu delivery at 33.6 percent and 18.5 percent, respectively. Together, the trio dominate the market and their scrappy competitors.

When business is good - usually if a driver takes around 1,000 orders a month - it's possible to make as much as 10,000 yuan ($1,534; 1,282 euros; £1,164). But, as Caixin reported, these kinds of salaries are far from representative. Around half of China's delivery couriers earn between 2,000 and 4,000 yuan, 28 percent earn up to 6,000 yuan, and a tiny minority make upward of 8,000 yuan.

Fengniao offers its employees insurance, deducting the cost from their wages at 2 yuan per delivery day. The couriers generally leave their children to be raised and educated in their home provinces.

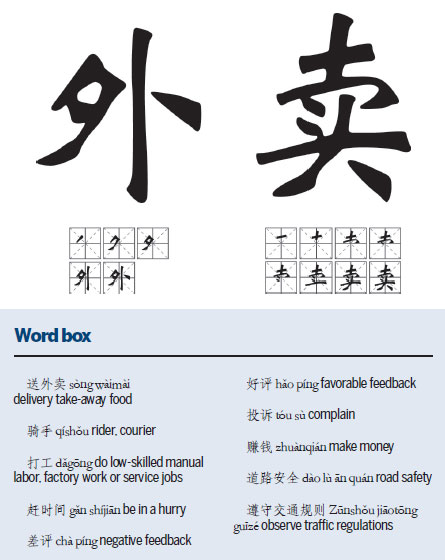

"It's a job you can do without a lot of skills," says a rider surnamed Lin, who is in his 30s. "Of all these kinds of jobs, your only other option is to dagong (打工 dǎgōng) " - referring to low-skilled manual labor, factory work or service jobs. "When you dagong, you may work more than 8 hours a day and you have to take orders from someone. When you deliver food, you get to be on the move, and work when you take an order; you earn more if you take more, less if you take less."

Still, Lin plans to change jobs. "The company is not doing well this year," he says. "I think it's time for me to move to a different field. ... They don't cover food or lodging, so after you pay your rent and feed yourself, there's not much left."

Last year, not for the first time, both Ele.me and Meituan were criticized by the China Central Television for allowing unlicensed restaurants to use their platform to sell meals, prompting an investigation by food inspectors in Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu, followed by an apology from Ele.me.

Both Lin the driver and Liu the analyst believe there are labor troubles brewing, as a sector swells by promotions and marketing adjustments are made.

"It's a demand created by subsidies," says Liu. "But since the end of last year, the market is contracting; it's stabilizing itself, so now there's internal competition for orders."

Driver Lin has seen it firsthand: "Last year, everybody was switching over to food delivery from other jobs. Our company was doing very well, giving all these discounts," he says, taking a break outside.

"Take a look at the streets there - everyone's a food delivery guy. It's gotten to the point now there are more deliverymen than orders being placed."

If what they say is true, mergers, refinancing and takeovers are likely to occur, along with possible layoffs. Yet the industry is sure to continue its expansion. But many of these employees, constantly striving to improve their speed, may well be left behind.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com.cn

The World of Chinese

(China Daily Africa Weekly 09/15/2017 page23)