The big picture

Illustrators struggle to draw attention to the value of their work

Two-and-a-half millennia after Confucius said that "one seeing is worth a hundred hearings", some bright spark in the English-speaking world took a leaf out of the great sage's book and came up with "a picture is worth a thousand words".

The West gave birth last century to an industry that employs millions of people who provide illustrations for books, cataloges, advertising and other media.

And, yet somewhere along the way, in China the old message seems to have been overlooked. Only in recent years has the printed picture begun to make an impact as a medium par excellence for getting messages across in many different areas.

| Children's picture books have been growing in popularity in the past few years. Xu han (inset), one of the artists who caters to this genre, created the iconic character Ali. Photos Provided to China Daily |

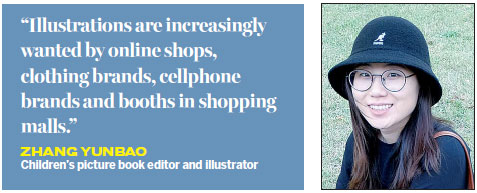

| One of the drawings by Zhang Yunbao, an editor and illustrator of children's picture books. |

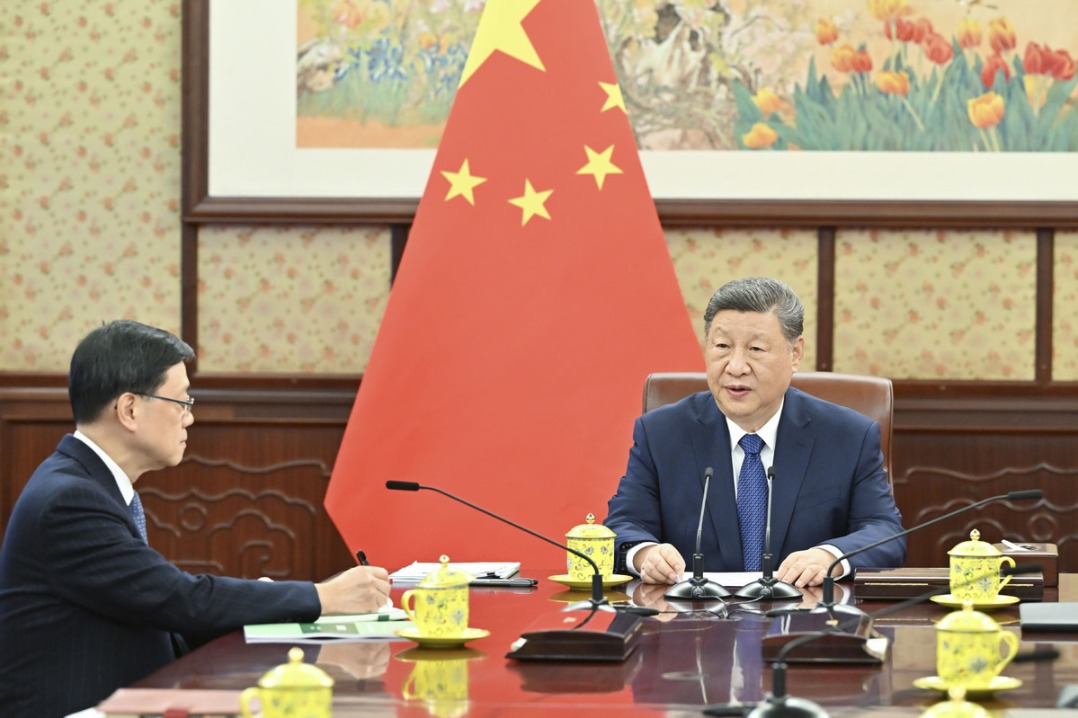

One of those who is aware of how far China has lagged behind - but is now seeing it making strides to catch up - is Zhang Yunbao, 29, a children's picture book editor for Beijing Poplar Culture Project Co. In her free time she draws commercial illustrations and makes her own picture books.

Zhang has worked in the field for five years and says she has noticed that in the past two years demand for both commercial illustrations and children's picture books has begun to take off, "which holds the prospect of a much bigger market in coming years".

"You can see that illustrations are increasingly wanted by online shops, clothing brands, cellphone brands and booths in shopping malls."

Over each of the past 10 years, sales of children's picture books have grown by an average of 10 to 12 percent in China, says Hou Mingliang, founder of IlluSalon, an organization founded in Beijing in 2014 to promote the use of illustrations in China and bring together illustrators and customers.

Hou has worked in children's book publishing for eight years.

As China fulfils its mission of ensuring that most of its citizens are clothed, fed and feeling well-off materially, the public is developing an appetite for intellectual and spiritual nourishment that only education and the arts, such as music, literature and painting can give, he says.

Li Ajiu, 32, a freelance illustrator in Shanghai, says that just 10 years ago when she graduated from university, illustrated books were hard to come by in China, but now they are everywhere. That is partly because parents have come to accept the concept of picture books, she says.

Hou says: "Picture books with beautiful illustrations, good stories and creative storytelling will exert great influence on children, who construct the world and connect themselves with society through them. So good picture books are very important."

However, 85 percent of children's picture books are imported and only 15 percent are domestic creations, Hou says.

Chinese parents prefer to buy imported picture books for their children because the values reflected in the stories are expressed in more creative ways and the quality is generally better than that of domestic works, he says.

"And for publishing houses, good-quality imported picture books - particularly ones that have won awards - are safer in the market."

Some people attribute this to the longer history of the illustration tradition in Europe and the United States, which cultivate highly talented illustrators.

Hou and Zhang, say many other factors are hampering the growth of the domestic illustration industry.

Zhang can recall few cases in which those who have ordered illustrations from her have offered a contract for her to sign. In most cases the only communication is by email and, without legal protection, some illustrators have to fight to get paid even after their work has been used.

Apart from requiring artistic talent and training, creating an illustration is time-consuming, and most illustrators who have not made a name for themselves struggle to survive on meager earnings. In fact, many of Zhang's illustrator friends say trying to make a living from their art is out of the question.

"They all love painting, but they have to live," she says.

Han Dan, 28, an illustrator who is known on the internet as Ghost Master, is an editor at Chemical Industry Press in Beijing. The lethargic growth in the publication of original picture books in China is partly the result of a dearth of picture book editors in publishing houses and elsewhere she says.

Zhang says: "Apart from illustrators, most people do not know about illustrations, what kind of illustrators they need or what kind of creative styles they want. People in other fields know little about art and painting."

For Han, another problem is the limited scope that illustrators have for selling their work.

"In China, picture books are mainly for children, and that means illustrators have a very limited space in which to express themselves."

Hou says that in Europe, illustrations were originally created by people to express their ideas or imagination on canvas. Some of the more personal illustrations that carried the wisdom of older generations may have been shown to the young as a means of education.

He cites The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter, saying that Potter originally just painted for herself without thinking about publishing. But after she showed the stories to a friend, he encouraged her to publish them. Peter Rabbit then became a popular picture book, which has become a classic.

"Many European illustrators draw very personal stories and then have them published," Hou says.

Han has rarely drawn commercial illustrations because "they usually don't like my style, which is cool, not that kind of warm or light style".

She has been working intermittently on stories about ghosts living in another world.

"I have talked to people on an online illustration platform. Obviously what they are looking for are illustrations for children books, so for them weird or cold, dark themes and colors are out.

"I know some Chinese illustrators who are really good. You may say they lack creativity compared with people in Europe or the United States but that's because they cannot express themselves fully."

To gauge the quality of illustrations in a certain country you have to see the general level of the illustrators, not just a few of the top ones, Hou says.

"Maybe this is going to offend some people, but the average level of Chinese illustrators is low. Many are just craftspeople who are good at technique but lack the quality to become masters because they don't have a big enough reserve of culture, including literature, music and painting.

"China's arts education is twisted. Students who go to fine art academies are usually those who may not be able to enter general universities. Ideas are most important for illustrations and the images are secondary.

"So there is still a long way to go. Nowadays, Chinese people, on average, read no more than five books annually, compared with more than 60 in Israel."

College teacher Xu Han creates stories about Ali, the popular red fox. Now he is directing a movie about the character.

He says that when he creates the picture books, the biggest challenge he faces is writing good stories rather than getting the painting technique right.

"The core of a picture book is the story. To write a good story you have to build up a big collection of ideas from everyday life," he says.

The task that illustrators or designers face covers more than just artistic technique and form. It also entails trying to express oneself through the content, Xu says.

Zhang says that when she was deciding which university to attend her father, who always encouraged her to chase her dreams, suggested that she should go to a comprehensive university rather than a special one.

"When I was little, my father told me to find the thing I really love and pursue it as a career. Of course, academies of fine arts have their advantages, with better faculties and richer artistic perspectives for students.

"My father said, 'I know you love painting, but at an academy of fine arts you will be surrounded by nothing but arts. If you go to a comprehensive university there are various kinds of things you can learn about, which I think is better for your development'.

"I personally believe that illustrators need to care about more than painting - things such as literature, movies, theater, photography or child psychology. You also need to know about society. These things are connected."

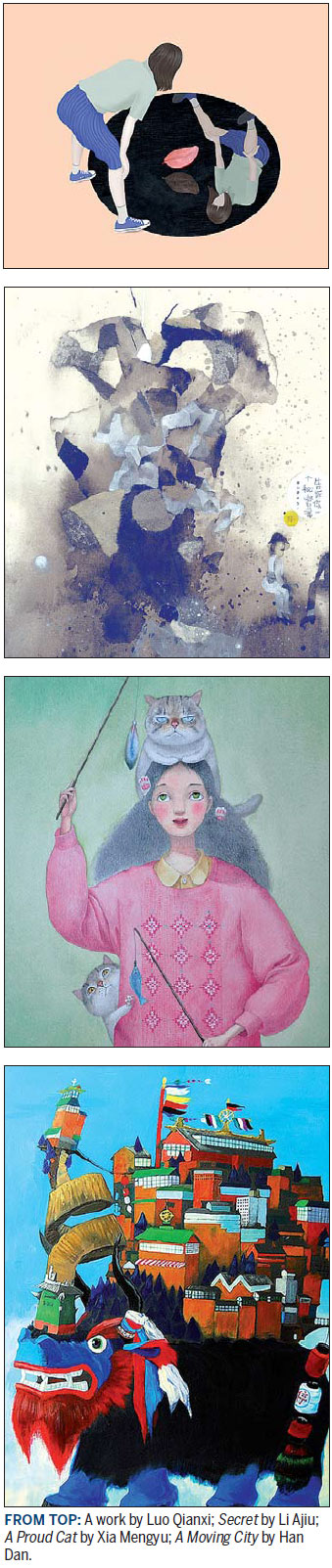

Luo Qianxi, 26, a freelance illustrator in Beijing, says China's illustration industry lacks organizations or agencies that can help creators promote their works.

"Illustrators spend most of their time and energy on creation. They don't know how to find customers or promote themselves. On the other hand, there are many well-developed organizations and agencies in Europe that help illustrators promote themselves and find customers. They also have good platforms to sell their works," Luo says.

In addition, in Europe people generally are more familiar with the illustration industry and often support and respect illustrators' works, she says.

In China, piracy is also a big problem, says Xia Mengyu, another freelance illustrator.

However, Hou believes that in the future illustrations will become mainstream in China and even part of everyday life. They will appear everywhere, and people will use them to decorate their houses or to promote their products, he says. Good works will be collected and stored.

"This is an audiovisual era, and the day will come soon."

yangyang@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 01/13/2017 page16)

Today's Top News

- The farmer, the snake and Japan's memory hole

- Crossing a milestone in the journey called Sinology

- China-Russia media forum held in Beijing

- Where mobility will drive China and the West

- HK community strongly supports Lai's conviction

- Japan paying high price for PM's rhetoric