A land shaped by water's ebb and flow

Challenge has created mentality among Chinese that almost any problem faced by the nation can be solved by engineers

Science writer Philip Ball believes water has played a key role in determining China's destiny.

This is the main argument of his new book, The Water Kingdom: A Secret History of China, which examines the country's long history through the prism of this vital aspect of its physical geography.

"China has had to develop a relationship with water that is unparalleled. You have a combination of factors that you don't see anywhere else in the world," he says.

| Philip Ball says he has been interested in Chinese culture since he was a teenager. Nick J.B. Moore / For China Daily |

"You have places like Bangladesh, where there is a constant risk of extreme floods; and the Middle East, where there are always problems of water shortage; but China has to deal with both."

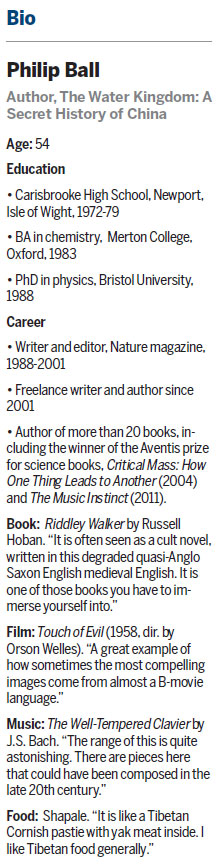

Ball, 54, was speaking outside the British Library near St Pancras in central London, where he is currently researching a new book.

He fully acknowledges that water is not the only perspective to see China from but it is a useful prism.

"What I hope is that by narrowing the focus to this particular window, it enables you to tell an extraordinary and surprising amount, not just about Chinese history but politics, culture, art, philosophy and language even."

Ball says water would not necessarily be a particularly useful vantage point for the history of his own country, famous for its rainfall.

"Every country and civilization has had to be close to water and have a relationship with water. In the UK, for example, we have plenty of it, as a whole, and it is just a matter of making sensible use of it."

The writer says it is no accident that one of the heroes of China's history, Emperor Yu, founder of the Xia Dynasty (c. 21st century-16th century BC), was effectively a hydraulic engineer.

He created a river system involving irrigation canals that prevented farmland from being flooded.

"He is not like a Noah figure who rides out the flood. He is someone who takes matters into his own hands and introduces engineering measures such as carving channels and dredging rivers to make floods subside.

"Like many people in Chinese myth and legend he is more of a remote administrator figure, unlike the sharp personalities you get in Greek or Norse myth or, indeed, with Noah who was the progenitor of the whole species (according to Christian doctrine)."

Ball says China's essential water problem is that water flows from the mountains of the west to the seas in the east but the challenge throughout history has been getting grain from the farmlands of the south to the north.

One of the great engineering solutions to this was the Grand Canal, some of which dates back to the 5th Century BC, which links the Yangzte and Yellow rivers.

"The Yangtze valley is below the Yellow River valley so you have got an uphill gradient going north. So you have this contrast of the water-poor north and the water-rich south," he says.

One of the China's modern grand schemes is the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, which aims to channel water from the Yangtze in southern china to the north through three canal systems. The $79 billion (74.3 billion euros; 62.3 billion) scheme, which will shift 44.8 billion cubic meters of water, is one of the world's most expensive engineering projects.

"It actually goes under the Yellow River through tunnels. It would be hard to find any other nation prepared even to contemplate something in this scale but China has the capacity to do this."

Ball, who was brought up on the Isle of Wight off the south coast of England, studied chemistry at Merton College, Oxford before going on to do a doctorate at Bristol University in theoretical condensed-matter physics.

After university, he went to work for Nature magazine, the leading British science publication that has been in existence since Victorian times, as a writer and editor on physical sciences.

It was while on a three-month sabbatical from the magazine in 1992 he made his first visit to China.

"I would say that from a teenager I had this interest in Chinese culture and under this very enlightened scheme Nature had, I thought this is my chance to finally go," he says.

He made use of his existing contacts there and spent the first month visiting science laboratories across the country and then generally traveling around.

"Looking back, it was an interesting time to be there (the year of Deng Xiaoping's Southern Tour which unleashed economic reforms) but it was still tough to travel in China."

Ball now makes regular annual trips to China and acts as a consultant to the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics.

"I go there and speak about the work they are doing, which relates to the molecular structure of water, an area I have long been interested in.

"Over the past 10 years I have pretty much gone to China every year with my family. I have a lot of contact there and friends in virtually every Chinese city."

Ball left Nature in 2001 (although he still contributes to it) to focus on writing books, of which he has published around 20.

Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another in 2004 won the Aventis prize for science books, and The Music Instinct in 2011, about why music matters to people, prompted a huge debate.

"I have always done music in one way or another. I played in bands in Bristol and I wanted to find a way of writing about music drawing on my scientific background."

His new book contains many themes that are still relevant to China. Only in 2007, the Yellow River, whose origin is the Qinghai Tibet plateau, dried up for 10 months before reaching the sea.

"It had happened in the historical past but this was a real warning and a real shock. It was to do with overuse of river water, too much being taken out for industrial use, agriculture and irrigation. Over the past 10 years, management of the river seems to have been getting better," he says.

Ball says China's water challenge has created a mentality among the Chinese that almost any problem the country has can be solved by engineers. Until recently many of the country's leaders including Deng Xiaoping and Hu Jintao have been engineers.

"I think that is part of the reason why China has had this appetite for huge engineering projects. There is a view in the West that they should perhaps be more like China and that there be more scientist and engineers in positions of power."

As well as being fascinated by its water history, Ball has a deeper commitment to China with he and his wife having adopted a Chinese baby in 2006. Mei Lan is now 11 and the elder of their two daughters. The book is dedicated to her.

"That is the reason why we go back to China a lot because we are keen she has contact with her Chinese roots," he says.

All the family are, in fact, now learning Mandarin.

"I can read menus in restaurants so I know what I am ordering, and get a taxi to get around. I am not sadly able to read the Tang Dynasty poets, but, you know, one day."

Ball, also a judge of this year's Baillie Gifford prize for non-fiction, is turning his attention away from China for his next book, which will be about modern myths.

"I am struck by how many stories such as Frankenstein, Dracula, Jekyll and Hide and even Sherlock Holmes have become modern myths while perhaps having mediocre literary credentials."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 12/16/2016 page32)

Today's Top News

- Xi calls for promoting volunteer spirit to serve national rejuvenation

- Xi chairs CPC meeting to review report on central discipline inspection

- Reunification will only make Taiwan better

- Outline of Xi's thought on strengthening military published

- Targeted action plan to unleash consumption momentum

- Separatist plans of Lai slammed