Tracing the tracks of metamorphosis

Railroad cargo can reveal fascinating trends, such as which areas are likely to thrive in the new economy and which are not

Difficulties fall into different categories. In a time of prolonged economic slowdown (or, as some may say, hanging on the cliff of a recession), difficulties abound.

And people may not be able to tell one category of difficulties from another - such as which ones are inevitable, representing the cost that must be paid for the economy's renewal, and which are the truly unwanted and might undermine the economy's future growth.

Now that China is some two years into its agonizing transition and a month-by-month slowdown in many indexes, it is gradually becoming clear which of its difficulties may be less dangerous than others.

Take the railway throughput figure, for example. It used to be considered one of the most reliable benchmarks of the overall state of the economy.

According to a recent report by Caixin, an independent business journal, the cumulative railway throughput was 10 percent to the negative compared with the same period last year. And that was after the same index's continuous decline for almost 20 months. Bad, isn't it?

Consider the fact that Chinese railways devote around half of their capacity in cargo transportation to the shipping of coal, a main resource for energy, heating and heavy industry, environmentalists may celebrate this piece of news, because it may indicate that the country's use of coal, and consequently emissions of pollution, is really close, if not past, its peak.

In fact, according to data from the National Development and Reform Commission, from January to June, China produced 1.63 billion metric tons of coal, 7.9 percent less than the same period last year.

For people working in state-owned enterprises, however, this is depressing news. Not only does it mean the closing of more coal mines and layoffs for more miners, but also less production of steel and cement, and indeed, less revenue for heavy industry across the board.

At the same time, it is also reasonable to assume that since there was already so much of a drop in coal transport (and related products), there wouldn't be a major setback in the amount of other goods. More things were still produced and sold to consumers at a time when energy use was cut and, in many cities, wages no longer showed as strong an increase as before.

On the macroeconomic level, the railway industry's declining coal delivery unmistakably shows the increasing effects of China's reduction in its once rampant excesses in industrial capacity, which had annoyed environmental groups and international competitors.

One would be curious to learn if there is any change in the primary destinations of the cargo delivery. It is also reasonable to assume that many cities in North China, long famous for their heavy industries and mining operations, may have dispatched fewer shipments.

Some cities in South China, with a large base of newly rich consumers and import services, may have seen an increase in their shipments to other cities.

Moreover, if the change in the railway cargo map in the first half of the year grows into a trend, it would be a starting point of the whole country's new economic geography.

In overall terms, as an inevitable cost of a national transition, many cities in North China, with the exception of a few around Beijing, will become less important, producing a smaller variety of goods and showing slower growth.

By contrast, the cities in South China, especially those with favorable trade conditions, new energy resources (such as nuclear) or relatively abundant labor supplies, will continue to attract new investors and migrants.

The emerging divide may also affect the nation's fiscal and financial picture, in which more central government funds will be diverted to the rescue and revitalization of the northern cities and relocation of local workers, and most southern cities will be left on their own to compete for market-economy opportunities.

This set of circumstances may make it clear where the gravest challenge to China's transition will be located. Most likely it will be in its rustier, more old-fashioned northern cities.

In the meantime, it won't take too long for a new round of intercity competition to create a new generation of manufacturers and services in the southern cities.

The author is an editor-at-large of China Daily. Contact the writer at edzhang@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 08/19/2016 page10)

Today's Top News

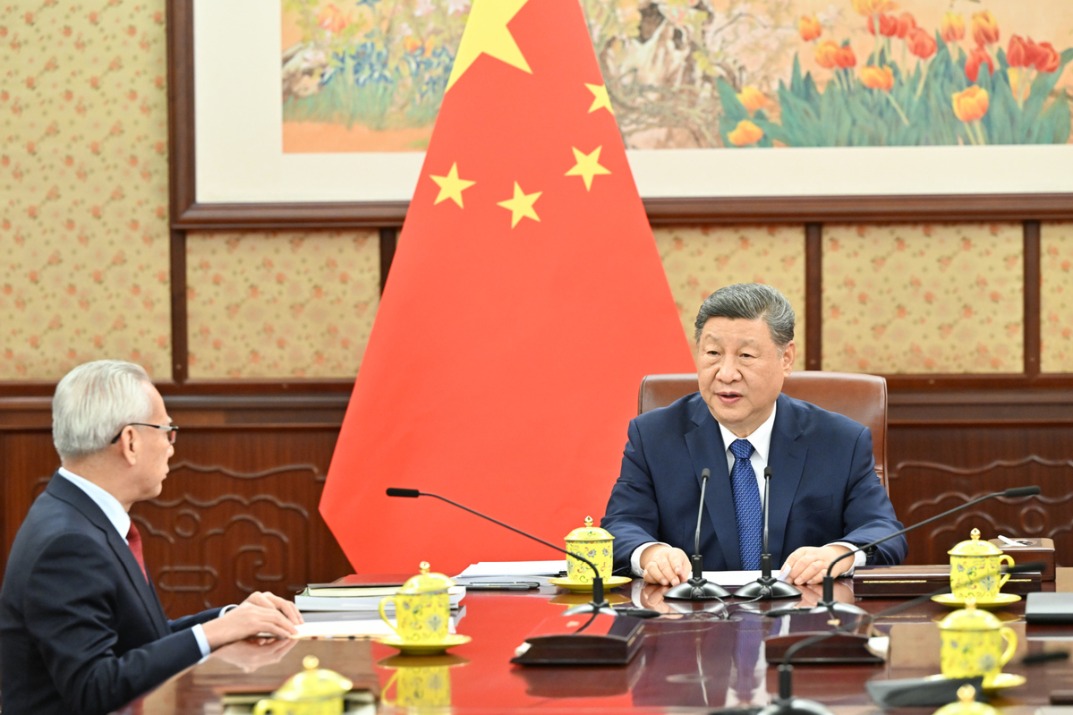

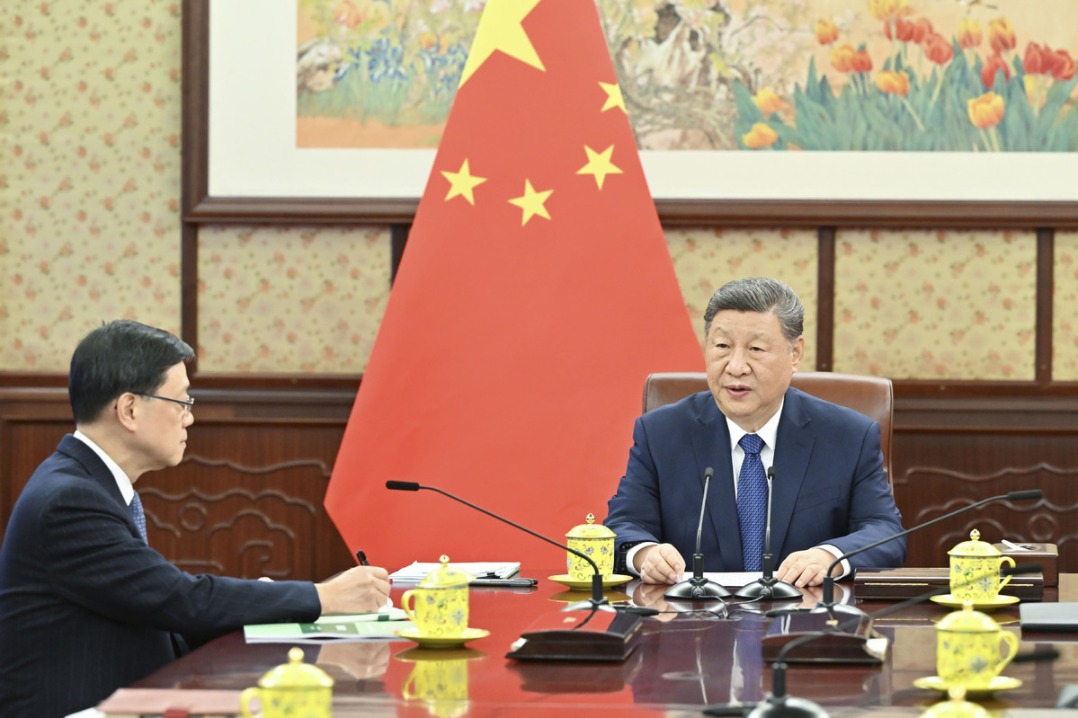

- Xi hears report from Macao SAR chief executive

- Xi hears report from HKSAR chief executive

- UN envoy calls on Japan to retract Taiwan comments

- Innovation to give edge in frontier sectors

- Sanctions on Japan's former senior official announced

- Xi stresses importance of raising minors' moral standards