Axis of global economy turning east

Author of new book asserts Asia would have risen quicker if not for the US' dominance in the 20th century

Gideon Rachman believes the balance of world power is now inexorably tilting east.

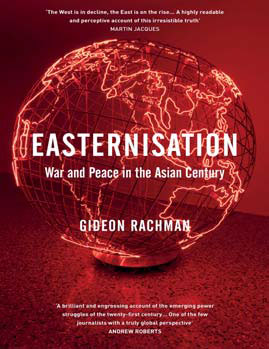

The journalist and author argues in a new book, Easternisation, which will be published next month, that this could be a pivotal point in history.

| Gideon Rachman says the Chinese might actually like a dealmaker like Donald Trump as president. Nick J.B. Moore / For China Daily |

"This rise in Asia starts with Japan and South Korea and then moves on to Southeast Asia but the real transformative event is when China joins that process of rapid industrialization.

"Because of the sheer size of China, that begins to shift the whole axis of the global economy."

Rachman - who was speaking in his office at the Financial Times in London, where he has been chief foreign affairs commentator for the past decade - believes Asia's dominance is almost an inevitable trend and would have happened much quicker if it had not been for the rise of the United States in the 20th century.

"European domination ends with the end of World War II and the decolonization that followed quite quickly afterwards. The US, however, steps in and replaces Britain as the most important power in the world."

Rachman says he felt the need to write the book because many in the West still do not acknowledge the shift in the global balance that has already taken place.

"There is an element of denial in the West about what is happening. I actually get two different reactions to the book though. The first is that there is nothing new in a sort of 'rise of Asia book' since people have been going on about it for 20 years. The second acknowledges the trend but says it is all a bit of an exaggeration."

He says during the writing of the book, his own perspective also changed.

"I started with a relatively crude view that there would be some sort of transfer of power to Asia. Although in broad terms that remains true, there were a couple of things that made me qualify that picture a bit.

"Firstly, there is no East in the way that there is a West. If you talk about the West, there is a Western alliance called NATO that links the Europeans and the Americans. Asia, on the other hand is actually very divided."

One of the questions Rachman addresses is why the West became dominant in the first place when populous China at the height of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) seemed unassailable.

"As the Chinese will always remind you, China was the world's largest economy and the dominant civilization. If you look at the big civilizational histories, there was a period when it was not at all obvious that Europe was going to be the dominant culture.

"You had a very flourishing Islamic culture as well as a dominant Chinese empire. It is really only with the European imperial age, which emerges for complicated reasons but largely because of a technological and war-fighting edge as well as the ability to develop markets, that gets them ahead."

Rachman, who recently was awarded this year's Orwell Prize for journalism after twice before being shortlisted, dates the beginning of Western dominance to the end of the 15th century with the arrival of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in Asia.

"This heralded in a 400-year-period largely synonymous with European domination with the great empires being the British, obviously with India and so on, the French in Indochina and the Dutch in Indonesia. This period begins to drain away after the end of World War I because of the weakening of Europe and the rise of the US."

Rachman was born and brought up in London but his parents were South African of Polish and Lithuanian Jewish descent.

"I think it was fortunate for me that they left since apartheid South Africa was not a great place to grow up in even if you are white. I think because of my slightly international background and just the way my family was, I was always as interested in international politics as domestic."

After studying history at Cambridge, where he took a first, Rachman joined the BBC World Service before going off to freelance in the United States.

He joined the Economist in 1990, where he had various roles, including spells in Bangkok as Southeast Asia correspondent and Asia editor as well as five years in Brussels.

He moved to the Financial Times in 2006, where he now has a roving global brief.

"They were initially looking for a Europe commentator but the brief has actually evolved into being more global. It is a sort of mad job because nobody can be an expert on every political development in the world.

"I travel a lot but there are periods when I don't. I try to get out to as much as I can and I go to Asia and America quite a lot and, of course, Europe is just on my doorstep."

Easternisation is Rachman's first book after the well-received Zero-Sum World, published six years ago, which also partly examined whether the West was more vulnerable to a rising Asia in the wake of the financial crisis.

It is likely to prove timely with the renewed focus on the South China Sea after an arbitral tribunal in The Hague on a Philippines arbitration case which China has rejected. US President Barack Obama, with his pivot to Asia, has already made clear where US foreign policy priorities lie.

"It doesn't make sense for America to spend 90 percent of its time worrying about the Arab world or even Europe now. The 21st century is clearly going to be in economic and, increasingly, in geopolitical terms, about Asia and America."

Rachman believes the Chinese might actually be more open to a Donald Trump presidency than many would assume.

"There is quite a lot of interest in the idea of a Trump presidency because they think Trump is a dealmaker, which is what they like, and he has also sounded very uninterested in the Japan and South Korea security alliances, which are the bedrock of American power in Asia."

"(Hillary) Clinton, on the other hand, is associated with Kurt Campbell (former US assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs) who was important in getting the (Asia) pivot going."

He says it is important not to underestimate the power the United States still has in the world.

"I use (in the book) what is not an obvious example. I talk about the whole FIFA case and the way that America can suddenly break up this international organization. This is clearly because people are using the dollar and are using American banks. They therefore get drawn into the web of the United States legal system."

Rachman believes that despite those who argue otherwise, the rise of China is now a permanent geopolitical feature.

"You get these recurring debates in the West, where you hear people saying, 'Well, surely this is not going to go on forever and the whole thing will blow'. It is clearly not going to be the case. You have only got to look at the development of the West, which went through periods of massive turbulence. Just look at the American Civil War and the military defeats of Japan and Germany (after World War II)," he says.

"This didn't hold these countries back for long. China has somehow figured out how to do industrial development and achieve rapid economic growth and that doesn't necessarily disappear."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 07/22/2016 page32)

Today's Top News

- Chinese landmark trade corridor handles over 5m TEUs

- China holds first national civil service exam since raising eligibility age cap

- Xi's article on CPC self-reform to be published

- Xi stresses improving long-term mechanisms for cyberspace governance

- Experts share ideas on advancing human rights

- Japan PM's remarks on Taiwan send severely wrong signal