Testing times

As China strives for gender equality, female scientists are still struggling to overcome social and cultural blocks

Take a look around any college lecture hall or company boardroom in China today and you'll see far more women than you would have 25 years ago.

In the nation's laboratories, however, it's a different story.

| Nobel Medicine Prize co-winner Tu Youyou receives her medal from King of Sweden Carl XVI Gustaf during the 2015 Nobel prize award ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall on Dec 10. Photos Provided to China Daily |

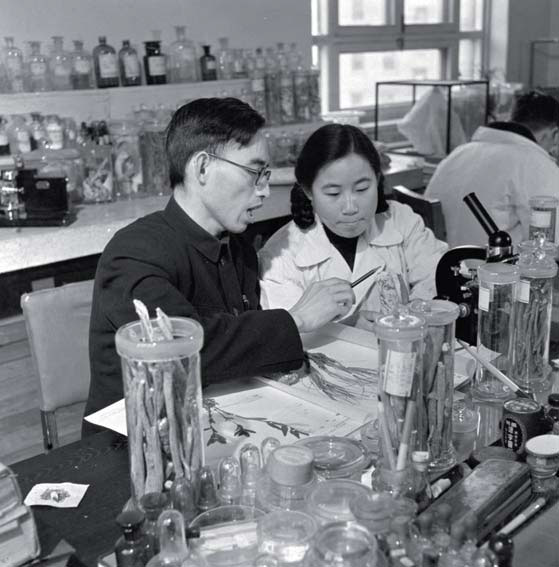

| Chinese scientist Tu Youyou working with Professor Lou Zhicen in the 1950s. She was an intern at the time. |

Despite a growing number of Chinese women studying science disciplines at all academic levels, relatively few are actually going on to have careers in the field, let alone heading up major government-funded projects.

Insiders say female scientists are still hindered by social and cultural factors that women in other fields have largely been able to overcome, with the biggest hurdles undoubtedly related to starting a family.

A State Council white paper on gender equality in 2014 said women made up 52.1 percent of undergraduate students in China that year and 51.6 percent of postgraduate students. Yet for PhD candidates the proportion of women dropped to 36.9 percent.

This can in part be attributed to the fact that postgraduate degree holders don't start their career until their late 20s, which is about the time most Chinese women have their first child (the average age was 28 in the 2010 national census).

Postponing a family can cause complications. In China, it's widely held that a woman should have her first child under the age of 30. After that, single women, especially those with advanced degrees and higher incomes, can struggle to find partners.

So the timing poses an obvious dilemma - and not just for the female scientist.

Funding for scientific research is often time-sensitive, so losing a team member can be a major blow if it delays a project. Plus, in China, employers are responsible for covering maternity pay, not social insurance, and there may not be enough surplus funds to hire a temporary replacement.

"The Chinese government allows women to take six months of maternity leave, but I'm not sure this really helps women who want to have a career in science," says Li Peng, a professor of life sciences at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

She warns that the current conditions open the door to potential gender discrimination.

"Any project leader will put the schedule first," she says. "If the research team doesn't have the extra funds to cover a researcher leaving for half a year, which is usually the case, a project leader will probably avoid recruiting a childless woman to the team in the first place."

Li, who was elected to the Chinese Academy of Sciences in December, has juggled her acclaimed scientific career with being a doting mother, but it has not been easy.

"It's like working two full-time jobs," she says. "I work from 8 am to 7 pm doing experiments, writing papers, applying for grants, teaching students and attending academic meetings and activities. And then I go home to take care of my daughter (now 19). I attended her school activities and took her on trips, and things have gotten tough when she's been sick. But, of course, I really enjoy my time with her."

Li is a rare case, though. According to estimates by Wang Zhizhen, a biophysicist and a fellow member of the CAS, women account for only 8 to 10 percent of China's science professors, and just 5 percent of principal investigators leading national-level research projects.

She says this is not because women are less competent or qualified, but because they tend to be more easily affected by social factors than men.

The situation of potential discrimination could be further compounded by the government's decision to ease its decadeslong family planning policy and allow all couples to have two children, Li suggests.

"Either female scientists have to cut their maternity leave short or the social insurance system needs to cover the costs; they're the only solutions to this problem," she adds.

Li Na, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and applied mathematics at Harvard University, says Chinese women in many professions face a similar dilemma. "All they can do is a make a decision based on their priorities," she says. "Some principal investigators just have to take the risk that they'll never be able to have children."

She proposes that the authorities cut maternity leave to three months, as well as make it easier for certain parents to use childcare services by offering subsidies.

World of change

A recent study has shown that female scientists are in the minority worldwide.

In October, the South African Academy of Science released a report on a survey of 69 national science academies - believed to be the first of its kind - that found only 12 percent of all members are women.

Furthermore, it showed just 6 percent of China's top-level researchers are female. This compares with 10 percent in Europe and the United States, although both have much smaller populations. (The highest proportions were in South American and African countries, which ranged between 19 and 27 percent.)

Jin Feng, a researcher with the Shanghai Engineering Center for Microsatellites, says of the 70 people in her department, 20 are women.

Yet the 32-year-old, who is a specialist in electromagnetic fields and microwave technology, says things have definitely improved over the years.

She cites stories heard from female colleagues around in the 1970s and 1980s who told her that, back then, research facilities lacked even basic amenities for the few women there were. "Some places didn't even have toilets for women," she says.

As a result, women were usually not given senior posts that required a lot of traveling, as they were unable to share accommodation with men, which was inconvenient and ultimately pushed up costs.

Most facilities have been updated to make it easier for female scientists, but Jin says some outdated attitudes have lingered.

"Certainly, there is still a bias against women in China," she says. "We're still seen by some people as 'too emotional' for science, while many ignore the fact we tend to be detail-orientated - more so than men - which can be decisive in achieving success in this field.

"Male scientists do have their advantages, but they're to do with physical rather than mental ability. They can carry heavy equipment, for example."

Women have proved they have the brains for any task: they have outnumbered men at China's universities since 2009 and at its graduate schools since 2010, according to data from the Education Ministry.

Once almost entirely focused on the liberal arts, such as languages, in the early 2000s female students began to major in male-dominated fields like business administration, sciences, engineering and technology.

Today, women account for roughly 40 percent of the 70 million or so sci-tech workers in China, according to the China Women's Association for Science and Technology.

However, compared with the business world, women in science still have a way to go to catch up with their male counterparts.

According to the 2016 survey of Chinese mainland companies by Grant Thornton, the multinational accounting firm, 30 percent of all senior executives are female, higher than the global average (24 percent). Meanwhile, only 16 percent of enterprises did not have women in their top management layer, down from 25 percent a year earlier.

Academic studies suggest this could be down to women being given extra credit when they show leadership skills.

For one study, Klodiana Lanaj at the University of Florida's Warrington College of Business Administration and John R. Hollenbeck at Michigan State University's Eli Broad College of Business recruited 181 MBA students in the US, of which 28 percent were women. They were organized into teams of five, including at least one woman, and after six weeks were asked to rate each other in terms of leadership.

The results proved a countervailing bias, showing that when women exhibited good organization, coordination and problem-solving skills they were rated higher than men who demonstrated the exact same qualities.

"When women's assertive or take-charge initiatives are in the service of a team, they not only are accepted but make a greater impression than similar endeavors by men," Lanaj was quoted as saying by Business Insider.

Li at Tsinghua University argues, however, that such a trend has yet to reach the world of science.

"When your peers review a research paper, they evaluate your work on what you have discovered. No one will consider whether this work was done be a man or a woman," she explains.

"If you are a woman who wants to be successful in science, first you have to be very strong," she adds. "As for what society can do to improve conditions for female scientists, it just needs to show more support, understanding and tolerance."

chengyingqi@chinadaily.com.cn

| Women account for roughly 40 percent of the 70 million or so sci-tech workers in China, according to the China Women's Association for Science and Technology. Photos Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 05/06/2016 page1)

Today's Top News

- Takaichi must stop rubbing salt in wounds, retract Taiwan remarks

- Millions vie for civil service jobs

- Chinese landmark trade corridor handles over 5m TEUs

- China holds first national civil service exam since raising eligibility age cap

- Xi's article on CPC self-reform to be published

- Xi stresses improving long-term mechanisms for cyberspace governance