Academic debunks Sino-Africa myth, again

Latest book deals with unfounded claims that China looks at continent as a place to grow food for itself

Deborah Brautigam believes that many commentators who should know better continue to misrepresent China's engagement with Africa.

The US academic insists the relationship still gets painted as either neocolonial, resource-grabbing or somehow underhanded in other ways.

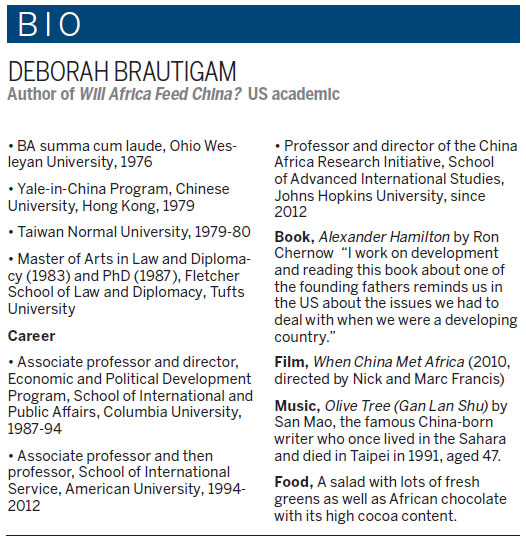

| US academic Deborah Brautigam is widely regarded as the world's leading expert on the China-Africa relationship. Mujahid Safodien / For China Daily |

"There are still a lot of myths. I think amongst the better publications, The Economist, Financial Times and the New York Times have got better but you still find quite a lot of fairly poor journalism.

"Even academics just collect a bunch of information from the Internet and don't sift through it very well to figure out what is real and what isn't. If you can't adequately do fact checking and you don't know the difference between good and bad information, it becomes very easy to write something that is full of falsehoods."

Brautigam, widely regarded as the world's leading expert on the China-Africa relationship, was speaking in the lobby of the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Johannesburg's Rosebank district ahead of the Second Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, or FOCAC.

She was also in Johannesburg to officially launch her latest book, Will Africa Feed China?, which aims to debunk another contention by some that China's agricultural aid projects in Africa, including various agricultural demonstration centers, are part of long-term master plan to deal with China's own food deficit.

"Anyone who knows about Africa is going to find it difficult to understand how a continent that itself has to import 10 million tons of rice is going to be able to supply the whole of China. The proposition looks a little dicey to me."

Her latest book is the first since The Dragon's Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa, in 2009, which itself was a minor publishing hit.

"It was what they call a crossover book. It sold in bookstores and to regular people as well as academics," she says.

Brautigam, highly engaging and with a ready wit, says she got the idea for her current book while spending a year as a visiting fellow at the International Food Policy Research Center in Washington in 2012.

"While I was there, someone from the African Development Bank made the proclamation that the Chinese were the biggest land grabbers in Africa. I just knew this was not true because I had written a lot about this area.

"Because such views were recycled and went unchallenged, I felt I just had to write this book."

Brautigam says her aim essentially is to set the record straight in what is a highly readable as well as informative account of China's complex engagement in this vital sector.

"The reality is that most Chinese involvement in agriculture is still largely limited to aid projects such as the 25 or so agricultural demonstration centers. I don't think these are part of a long-term plan to dominate African agriculture. They are just a part of South-South cooperation."

Brautigam looked at 60 Chinese agricultural projects in Africa and only the leaders of one that was involved in growing rice in Xai-Xai, in southern Mozambique, said they had any intention of exporting to China in the future.

"Even they said there was no way in hell they would be able to do it now because it was just not cost effective to export rice to China when it could be sourced from places like Vietnam where the shipping costs are lower," she says.

China imports mainly cocoa, sesame seeds, rubber, cotton and tobacco from Africa but the bulk of its food comes from developed countries like the United States.

"Around 95 percent of the corn imported into China comes from the US and Canada with soybeans coming from Brazil and Argentina."

Brautigam, originally from Madison, Wisconsin, did British studies for her first degree at Ohio Wesleyan University, from where she graduated summa cum laude.

This involved a spell at the University of Kent at Canterbury in the United Kingdom.

She then spent four years traveling around the world, living in Jordan and Thailand and also studying Chinese in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

"I wanted to see the world and it started out as a gap year but extended to four years."

At Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in Massachusetts, she emerged as a China scholar but began to fuse this with Africa when she focused on China's foreign aid programs in Africa for her PhD dissertation.

It was a fortuitous decision since the subject of China and Africa soon emerged from an academic backwater to one of major international interest.

This was particularly the case after the first FOCAC summit in Beijing in 2006, which was a spectacular affair with its processions of people wearing African dress and 30-foot-high posters of giraffes and elephants

"Suddenly the topic just broke out. I had been trying to make sense of it since the 1980s and so was in a fortunate position."

Brautigam, now the doyenne of China-Africa experts, is quick to deny that she practically invented the subject.

She points out there were a number of important earlier writers on China's political links with independence movements in Africa from the 1950s onwards.

"There were some wonderful people before me such as George T. Yu (another US academic) who wrote about the Tanzam Railway (the China-built track that links Tanzania and Zambia) back in the 1970s."

Brautigam says she still has to deal with a lot of paranoia in Washington about the China-Africa relationship, particularly in the security area.

"There are a lot of people who think that China already has military bases in Zimbabwe or in the Congo. It just isn't true. They have training operations in various places but we have these relationships, too."

She says perhaps the biggest single myth is that the Chinese just ship in their own workers to carry out projects and do not use local labor.

"This has never been true. Even in the 1980s, there would be a hydropower project or a stadium where there would be 20 percent Chinese workers and 80 percent local. Those proportions have remained fairly constant throughout.

"People say they have seen Chinese workers pushing wheelbarrows but the Chinese don't have this sense of hierarchy. If a Chinese manager sees a wheelbarrow that needs to be pushed, he will push it."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 12/11/2015 page32)

Today's Top News

- New engine powers cargo drone expansion

- China to boost intl cooperation on green tech

- Factory activity sees marginal improvement in November

- Venezuela slams US' 'colonial threat' on its airspace

- Xi: Strengthen cyberspace governance framework

- Takaichi must stop rubbing salt in wounds, retract Taiwan remarks