Center-stage and on the tips of their toes

Their parents are away working in cities, and their confidence has been dented by a culture that sees boys as a cut above. into the picture step teachers intent on restoring self-confidence through art

In August last year, Guan Yu, a ballet teacher from the Beijing Dance Academy, spent a few days in Duancun, a small rural town in the northern province of Hebei. "The day I arrived, at noon, I went to eat at a small restaurant. It was the height of summer. All around me, shirtless men were talking at the tops of their voices and happily washing down skewers of grilled meat with giant glasses of beer," he says.

As he waited for his food, Guan caught a glimpse of a girl jumping off a bicycle. She was Li Ziyi, a former student who quit his classes when she entered middle school earlier in the year.

| Guan Yu, of the Beijing Dance Academy, leads girls in ballet practice during an outdoor class in the Baiyangdian wetland in Hebei province. Photos by Gao Tian / For China Daily |

| Zhang Ping, Guan Yu's wife and fellow dancer, teaches at the ballet class in Duancun. |

"She came into the room. We were surrounded by clouds of cigarette smoke, mingled with the heavy steam coming from the tiny kitchen at back. She called out to me, but her words were drowned by the noise," Guan says. "Slightly taken aback, I stood there, not knowing what to do. That's when she came up and gave me a big hug, as if the rest of the room didn't exist."

Guan has been making weekly trips to Duancun, 100 kilometers from Beijing, since 2012 to provide free ballet classes for local children. "We go there every Sunday and return the same day, spending six hours on the road and about five hours teaching," the 45-year-old says.

One day in late September, in a purpose-built ballet studio in the basement of Duancun School, about 20 girls, most of them about age 9, were doing barre exercises under Guan's direction. They wore pink dance costumes and soft shoes, and each had tucked every lock of hair into a shiny bun on her head. Class had just begun and some latecomers were trying to sneak into the formation, pulling funny faces at their fellow dancers.

The youngest children on the outer fringes constantly sneaked glances at those beside them to make sure that they were making the right moves. All the instructions were given in French, the official language of ballet.

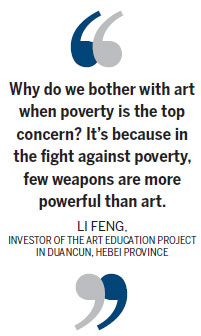

Li Feng is the driving force behind the project. "Why do we bother with art when poverty is the top concern?" he says, before answering his own question. "It's because in the fight against poverty, few weapons are more powerful than art."

Born in Beijing to high-ranking government officials, Li has led a reasonably privileged life, even during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) when all the schools were closed. "With no school to attend, I listened to Western classical music and read Renaissance history," says the 60-year-old investor, who returned to Duancun, his ancestral home, late in life and discovered little but despair.

"It's a feeling shared by many people - especially young men and women - in rural China. The only way out seems to be via the college entrance exam. But with the country's educational resources concentrated in the cities, even that way has been effectively blocked for most of them.

"Many choose to become migrant workers away from home, where they are bound to encounter discrimination in some form."

Convinced of the power of art to bolster confidence where traditional academic training has failed, Li decided to establish an art education project in 2012. It featured five fields of study: Painting; theater performances; wind and string instruments; choral song; and ballet. Free classes are held every weekend, with teachers coming from schools and groups in Beijing. Li pays all their expenses. To provide badly needed space, he and some friends built the Duancun School, which opened 18 months after the classes started.

"Of all the different types of art, ballet is the most challenging, and the one I most insisted on having," he says. "If you look at the way the girls dance, how they hold their chins up during a high leap, you'll understand my point. Ballet is not just ethereal, it's regal. Even a deep bow at the curtain call has a grand feeling about it. To learn ballet is to cultivate a firm, intense self in one's heart."

Having taught ballet for more than two decades, Guan is an expert. He had never taught children before, so he decided to return to a more basic, and sometimes buried, love of dancing. "This has to be a love affair from the start. Otherwise, we won't be able to stay," says Guan, who in his first official class encouraged his then slightly unruly pupils to perform Dance of the Little Swans from Swan Lake.

"I chose the dance because the children have grown up playing in the water," Guan says, referring to the town's five villages, simultaneously separated and connected by open water.

"Any art education is a form of aesthetic education. I want my girls to associate ballet with beauty, not pain, at first, although they'll eventually have to endure pain in their quest for beauty."

The girls danced in soft shoes for six months, before Guan decided it was time for them to try standard ballet shoes, whose hard toecaps assist performers to dance on the tips of their toes, or en pointe.

"One moment, they were learning to tie the ribbons and the next they were jumping around like fallow deer, spirited and spellbound," Guan says. "Within six months, all the girls could stand on the tips of their toes, something never before achieved by a ballet school in China."

Guan gives the credit to his students. "Young as they are, my girls are by no means like their pampered city sisters. I told them: 'I know it's painful, so you can shed tears if you want, but don't cry out loud.' I never heard a single sob in my class.

"They practiced nonstop after class. Their mothers sent me photos and video footage showing the girls practicing en pointe while, say, reading a book."

Li Ziyi was among the first students, and she remembers the moment the physical cost of ballet became apparent. "I was washing my feet at the end of a long day. Suddenly, Mom stared into the basin and shouted, 'What's that?' Two pieces of toenail were floating on the surface of the water," she says. "I hadn't felt any pain up to that point, perhaps I was too preoccupied with dancing. But for the next few months until new nails grew I was in hell."

The girls have danced for visitors from outside Hebei, and occasionally outside China.

"In their eyes, you see a determination and an untainted devotion unlikely to be found even among top dancers," says Gao Tian, a lawyer-turned-photographer who has shot many performances.

But these "jolly angels" were also vulnerable, as Guan and his dancer wife Zhang Ping discovered. "One day during a class break, a 6-year-old girl nuzzled up to me and asked in her thin voice, 'Teacher, can I call you Mom'?" says Zhang, who has taught in Duancun for the past three years. "Although I was surprised, I instinctively realized what she was asking for parental love."

With their parents working away in large cities, most of the Duancun girls have grown up with their grandparents and other older relatives, and their confidence has been further eroded by the local culture in which boys are seen as superior.

"Ballet gives them a long-sought opportunity to be center-stage and feel loved," Zhang says. "A girl once cried about her dark skin, so I told her that she had the most beautiful foot arch. She beamed, and said she'd never give up that arch for anything, not even lighter skin."

Guan's academy students used to teach the girls, but now he relies on himself and a small number of dancer friends, all older than 40. "What the girls need is not a big brother or sister, but a mother or father," he says.

However, "responsible parenting" often means being brutally honest. "Judging by their physical attributes, it would be just unrealistic for most of the girls to imagine a career in dancing," says Guan, who in April arranged for teachers from the National Ballet of China to hold a recruiting session in Duancun. "Every year they pick talented young girls and spend years training to prepare them for prestigious dance groups," he says.

None of the girls was chosen, but Guan was not surprised. "I saw them bursting into tears, knowing that this is just one of the numerous obstacles they'll encounter in their lives," he says. "I'm not here to change the trajectory of anyone's life. If a girl from my class is going to quit dancing temporarily when she enters middle school, or if she fails the college entrance exam and returns to her village to be a farmer or a housewife, that's life.

"But it's my genuine wish that she will treat herself to a piece by Tchaikovsky while cooking, or execute a beautiful twirl among the tall reeds," he says, adding that he has had great times "harvesting crayfish and collecting duck eggs", and other fun activities to which his students introduced him.

"Growing up nourished by the abundant beauty of Mother Nature, these girls can extract a kind of genius from their provincialism. To be with them is to reconnect with my own innermost yearnings for artistic experience," Guan says.

In one of Gao's photos, taken during the summer of 2013, four girls, including Li Ziyi, stand in a newly harvested cornfield, striking balletic poses and gazing at the sky. "Contrast is the theme - contrast between the budding young girls and the brooding clouds and the short, spiky stubble that forms the background, the contrast between the past and the future," Gao says.

Guan visited Duancun for the first time a few months before Gao's photo session. When one mother asked why her daughter should study ballet, he replied, "to become prettier and marry better".

The effect was immediate. "My wife tied the 6-year-old girl's hair into a neat bun, and I saw the indifferent expression on the mother's face change to incredulity mixed with pure adoration," he says. "One minute is all it takes to turn an impish duckling into Princess Swan," he says.

Li Ziyi was one of his first students. "When I first saw her, in March 2013, she was 12 and just like the other girls. Standing uneasily before me, she bit her lip and nodded at whatever I asked her," Guan says. "But then, when I knelt down and talked slowly to her, I saw the sparkle in her big black eyes.

"Teaching art is about teaching the notion of equality, because everybody is equal in his or her love for art and their love is equally precious. It's also about teaching openness, an attitude that lays the found-ations for any artistic pursuit and has at its heart an undaunted confidence," he says, reflecting on the meeting at the restaurant.

"The moment I felt the warmth of her embrace, I knew I had succeeded."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

| Li Ziyi, Guan's former student, helps younger girls during a class in Duancun. Photos by Gao Tian / For Chian Daily |

| Parental love is what the girls in Duancun need, says Zhang Ping. |

| Li Feng, who launched the art education project in Duancun, presents a certificate to a graduate from Guan's ballet class. |

(China Daily European Weekly 11/27/2015 page24)

Today's Top News

- Japan tempting fate if it interferes in the situation of Taiwan Strait

- Stable trade ties benefit China, US

- Experts advocate increasing scope of BRI to include soft power sectors

- New engine powers cargo drone expansion

- China to boost green industry cooperation

- Manufacturing PMI rises in November