Remembering the 'nine gentlemen'

Chinese heroes' dossier of evidence drew international attention to Japan's invasion in 1931

Opening a faded-blue file with trembling hands, Gong Jie had mixed feelings, at once nervous and excited to finally be seeing the documents her grandfather and several others had risked their lives for 84 years ago.

Gong Tianmin was one of the "nine gentlemen", a group of Chinese intellectuals who in 1931 secretly compiled a dossier of evidence to show Japan's true intentions after the Sept 18 Incident, also known as the Mukden Incident.

| In the UN Library in Geneva, Gong Jie opens the file that includes the evidence collected by her grandfather and his associates. The documents tell the truth of the Sept 18 Incident. Photos Provided to China Daily |

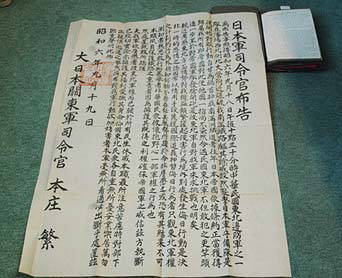

| The notice collected by the "nine gentlemen". |

The collection of documents and photos helped win support from the League of Nations, the predecessor of the United Nations, and exposed Japan's so-called Manchukuo state in Northeast China as a puppet government.

"Every night when my grandfather left home, he would always tell my grandmother that he was going out to obtain more evidence and asked her not to look for him if he didn't return," said Gong Jie, who lives in Frankfurt.

She saw the file for the first time in 2008 during a visit to the UN Library in Geneva. This year, the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, she says she wanted to highlight the work of Chinese who, like her grandfather, had attempted to prevent a war between China and Japan.

At 10:20 pm on Sept 18, 1931, the Japanese Kwuantung Army stationed in Northeast China blew up Liutiaohu Railway in Shenyang, Liaoning province, and blamed Chinese saboteurs.

Using the incident as an excuse, the next day, the Japanese bombarded the Chinese Nationalist Army's Beidaying Battalion as well as the city of Shenyang. The attack is regarded as marking the start of Japan's invasion of China.

The Nationalist Army's garrison in the city adhered to the policy of "nonresistance", and within months the Japanese had overrun all major towns and cities in Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang provinces, an area three times the size of the modern-day United Kingdom. The occupying forces declared its Manchukuo state in the northeast in March 1932.

At the time, the ruling Nationalist central government was struggling with internal issues, so it turned to the international community for a peaceful resolution.

The Foreign Ministry issued a strong protest, calling for a end to all Japanese military activity in China, and appealed to the League of Nations, which was set up in 1920 as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended World War I with the principal mission of maintaining world peace.

The Japanese army insisted China was to blame for the Sept 18 Incident and said their response was made in self-defense. They also claimed the Manchukuo state was established with the support of the local Chinese people.

Collecting evidence

To end the hostilities, the League of Nations sent a commission to China in April 1932 to investigate the cause of the incident and the establishment of the Manchukuo state. The team was headed by Victor Bulwer-Lytton, the second Earl of Lytton in the UK, and consisted of four other representatives from the United States, Germany, Italy and France.

The Chinese people saw an opportunity to protest directly to the Lytton Commission. Yet the Japanese army blocked any access, tightly supervising the delegation from morning to night. Residents and puppet Chinese officials were even given stock answers for any questions they might get from the commission members.

In one letter to his wife, Lord Lytton calls his stay in China "a nightmare" and compared the Japanese protection provided to him and his colleagues as like being in a prison.

At the same time, Gong Tianmin, a banker, and eight others in Shenyang, mostly physicians who studied medicine in the West, were collecting their evidence.

Due to their connections abroad, they had been informed in advance about the Lytton Commission's visit. "My grandfather thought the visit was a golden opportunity to let the world know the truth, and the group knew it could not miss the chance," Gong Jie says.

Photos were seen as the best evidence, so after the Manchukuo state was established the "nine gentlemen" pretended to take pictures of the "celebrating" Chinese but instead focused on the Japanese soldiers carrying loaded weapons and threatening locals with bayonets.

The dossier also included copies of a 1-meter-tall, printed notice commissioned by the Japanese Kwantung Army commander, Shigeru Honj, that were posted through Shenyang on the morning of Sept 19. The notice blamed Chinese saboteurs for the Liutiaohu Railway explosion.

"If the Japanese army had not been plotting the incident for a long time, how could it have managed to print so many big notices in such a short time?" Gong Jie argues.

The intellectuals also took pictures of a secret order by Japanese army to the Manchukuo authorities, proving it was a puppet state.

"The work to collect the evidence was all done in the highest secrecy because of the close supervision of the Japanese army," she adds. "All the printing and editing had to be done under the cover of night."

Showing the truth

In the 40 days running up to the Lytton Commission's arrival, the group had collected more than 400 pages of evidence. The documents were placed in a blue file, on which the word "truth" was stitched in English.

The group knew it could not hand the dossier directly to the commission, as the streets in Shangyang were full of Japanese police. So instead it turned to Frederick O'Neill, an Irish missionary in nearby Faku town who had known Lord Lytton since childhood.

"Once a Chinese gentleman named Gong Tianmin came to Faku to meet my grandfather, asked him whether he could help to hand in some documents to the Lytton Commission. My grandfather promised he would help," the missionary's grandson, Mark O'Neill, wrote his book about his grandfather.

The missionary wrote a letter to Lord Lytton to tell him about the dossier, and on the fifth day after the arrival of the commission he invited the peer and his secretary to a private dinner at the home of William McNaughtan, another missionary whose home was too small to accommodate the Japanese "protection" officers.

It was during this dinner that Lord Lytton first laid hands on the evidence collected by the nine intellectuals. The next day, he examined the dossier at the British consulate in Shenyang.

In its concluding report on October 1932, the commission said the operations of the Japanese army after the Sept 18 Incident could not be regarded as legitimate self-defense. And regarding Manchukuo, the report added that the state would not have been formed without the presence of Japanese troops and that there was no general Chinese support, and therefore not a genuine, spontaneous, independent movement, as the Japanese had claimed.

In February 1933, the League of Nations took a vote and condemned Japan's invasion of China, calling for the occupying force to withdraw immediately. Japan instead withdrew from the League of Nations in March 1933.

Although the work of the nine intellectuals did not prevent Japan from invading China, "they collected empirical, onsite evidence of Japan's invasion after the Sept 18 Incident", says Wang Jianxue, vice-president of the Society for Study of Modern and Contemporary Chinese Historical Materials.

When the Japanese army learned of the dossier that had been handed to the Lytton Commission, Gong Tianmin and his eight colleagues were imprisoned and tortured. One of them, Liu Zhongyi, died while in captivity. When they refused to reveal any details, the surviving eight were released on bail after 49 days.

Lord Lytton returned to England with the dossier, and it was later placed in the UN Library in Geneva, where is remains today.

"Despite all these efforts and the torture, my father hardly mentioned what he and his colleagues did for us," says Gong Tianmin's son, Gong Guowei, who first heard of the group's bravery in the 1950s in a speech by premier Zhou Enlai. "I think they thought they were just doing something that any responsible Chinese would do," he adds.

Chinesische Handelszeitung in Germany contributed to this story.

zhouwa@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 09/18/2015 page29)

Today's Top News

- Japan tempting fate if it interferes in the situation of Taiwan Strait

- Stable trade ties benefit China, US

- Experts advocate increasing scope of BRI to include soft power sectors

- New engine powers cargo drone expansion

- China to boost green industry cooperation

- Manufacturing PMI rises in November