Pieces of history

In the turbulence of the past century, many of China's cultural relics were looted, sold abroad or, even worse, destroyed. the reporter looks at State-owned antique stores and roles they play

Xu Qing says he can't remember exactly how many treasures have passed through his hands. The 56-year-old has worked at the state-owned Henan Provincial Antique Store for 34 years and has witnessed many major changes in China's policy concerning its innumerable antiques.

"I watched as an entire room of ancient scrolls were taken off the walls and sold to people. I watched as a whole batch of antique bronze sitting Buddhas were sold not according to their individual value but to their total weight," says Xu. "Today, the best of these things turn up - if they turn up at all - at auctions in and outside of the country and are hotly sought after by avid collectors who have no idea how long they will have to wait if they miss the opportunity to buy."

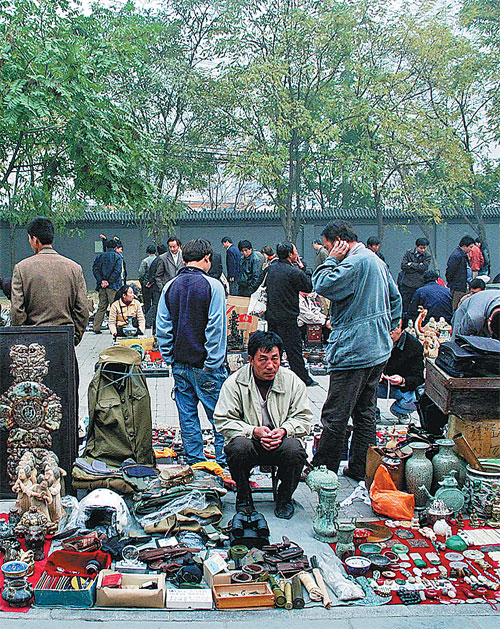

| Objects related to Buddhism are among popular displays at the antique markets across China. Fan Jiashan / China Daily |

| An antique trader from Henan province sells a porcelain pillow. |

Thirty years ago, state-owned antique shops were one of the few places in China where foreign currencies were accepted. "For foreigners, or people from Hong Kong or Taiwan, these stores were a window through which they could take a fascinating peek into Chinese mainland. For us, it was a way to earn US dollars, at a time when there were not many ways to do so," Xu says.

Xu says the antique stores, which operate at provincial or municipal levels, are the descendants of the privately owned antique shops that flourished during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), China's last feudal dynasty.

"In the 1950s, after the founding of the People's Republic of China, all private enterprises, antique shops included, were consolidated and incorporated into the state economy," says Xu. "Every major historic city had its own store. And a province like Henan, which has many historic cities and towns, was certainly entitled to have one provincial store of its own. That was really the beginning of our story."

One issue faced by antique stores was how to replenish their stock. "We offered to pay for 'old' stuff from average Chinese families, and people soon started to come," says Xu. He says people were willing to sell because they were living in poverty and had scant knowledge of antiques. "For those who were living from hand to mouth, saving a piece of antique jade for posterity is really not a major concern."

Things took a dramatic downturn with the commencement of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), a decade-long ideology-centered socio-political movement that shook China to its core. Today, it is believed this period wreaked havoc on the country's invaluable cultural heritage, most notably, antiques.

In an era when antiques were seen as symbols of a "rotting past" and were taken from the homes of their owners to be destroyed, the stores were a haven for the collective cultural memory of the Chinese, says Li Xuejian, from the Tianjin Municipal Antique Store. "Founded in 1960, our store had already earned its reputation among its peers by the time the "cultural revolution" broke out. Operation was effectively in limbo for the ensuing decade, but that didn't stop our staff from offering what they saw as real treasures their sole chance of survival.

"Mostly in their 50s at the time, these people, who had spent their whole life studying antiques, found it impossible to sit and watch while, say, a whole cart of bronze Buddha sculptures from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) were thrown into a factory's melting pot," says the 59-year-old. "A few of them stationed themselves at the gate of a bronze smelting factory in Tianjin. From time to time people would arrive at the gate with loads of antique bronze sculptures and wares, all collected forcibly from local families. There, they were dumped on the ground to be reduced to liquid metal."

"These gentlemen from our store would then contact the person in charge to secretly purchase some pieces at the same price as the raw material. In this way over the years, they saved a total of 20,000 pieces of bronze Buddha," Li says. "Today, all those men have passed away, but what they rescued, at the risk of their own lives, is still with us..."

According to Li, the decade-long confiscation of antiques from average Chinese families, often carried out by the so-called Red Guards, mobs of youngsters, resulted in many antiques being thrown together, lying in warehouses and untended.

"There were indeed numerous cases of antique porcelain being smashed, but luckily, not everything surrendered to the Red Guards was destroyed. Most of the time, they simply made a note of what they got, before putting the stuff in storage," Li said. "In the early 1970s, after all the havoc had come to an end, the government decided that provincial and municipal antique stores were to take charge of the stores of goods."

The goods remained in the antique stores until the end of the 1970s, when the government started to restore the reputations of many people who were persecuted during the "cultural revolution", and return their confiscated assets. "Through the entire 1980s and into the early 1990s, our store had been engaged in the return of antiques to their formers owners, based on the registrations kept by the Red Guards nearly two decades before."

If records had been lost, owners could also make their own claims. "People back then were so honest, there were very few false claims." Li says.

It was during this time that the sale of antiques to people from Hong Kong and Taiwan and elsewhere was reinstated. "The practice was first introduced in 1950, as the officially delineated role for state-owned antique stores at the time was to firstly collect state-level antiques for museums and secondly, sell the less-important ones for foreign exchange," says Xu, from the Henan store. "This was discontinued during the "cultural revolution", when China cut off almost all ties with the outside world. Such activities resumed in high spirit in the 1970s and reached a peak in the mid-1980s."

What seems downright absurd today is the fact that more often than not, the antiques were sold not as individual pieces with their own varying historic and artistic value, but in bundles and bags.

Asked whether there was a realization among those working at the stores that they were underselling valuable, or even invaluable things, Xu says that was not the case.

"The price, a tiny fraction of what the pieces command now, was actually quite high compared to our monthly salary of a couple dozen yuan, or a few US dollars," he says. "As far as I'm concerned, the biggest mistake we made at the time was to allow large number of antiques to go through the Chinese customs. Many of what we then categorized as second-rate and salable turned out to be much rarer or precious than first thought."

Despite the price, Xu says he would like to save money and buy something for himself if it was allowed. "According to the country's Law On The Protection Of Cultural Relics, people working at state-owned antique stores were forbidden to buy or trade in antiques," he says. "As a result, none of us dared to."

The law is still in place today, although people like Xu and Li no longer feel bound by it.

"With China embracing the market economy in the early 1990s, everything changed. The government publicly announced its intention to 'entrust our cultural treasures with the people', which was immediately interpreted as allowing more freedom among its citizens to trade antiques," Xu says.

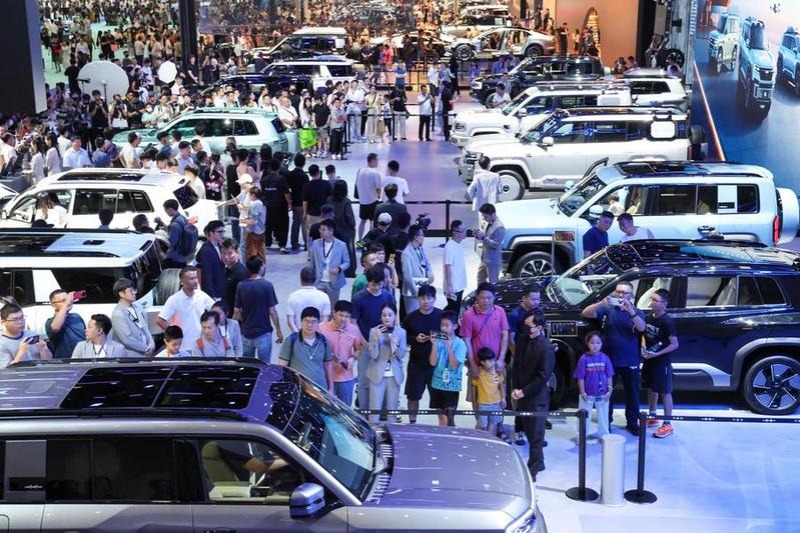

For the next decade, China's antique market flourished, giving birth not only to countless antique malls and open-air bazaars, but also to the darker world of tomb raiding and antique trafficking. Meanwhile, the government has sought to re-evaluate its former antique export policy. Large quantities of antiques previously under the charge of state-owned export companies were transferred to antiques stores, where they had their value reappraised by experts. "Control over the exportation of antiques was considerably tightened," says Li, from the Tianjin store. "The era when Chinese antiques were bought up by the richer parts of the world was gone once and for all, and Chinese were to take the lead in the purchasing of their own cultural treasures."

Antique stores still have a role to play, an even bigger one. "In a market saturated with fakes, state-owned antique stores were viewed by the general public as one of the very few places to buy something authentic. We are brand names."

And for the first time, those who spent decades working in the antique stores have started buying items. "It's so exciting out there, the whole world of collecting. And we had been standing on the doorstep for so long," says Li. "No one seems to bother with the law that much."

Many of the staff from the state-owned stores have approached their former customers, according to Xu. "A colleague of mine flew to Hong Kong a few years ago, where he was led through full rooms of scroll paintings, all tied up in bundles. He was asked to pay a certain price for each bundle, without being able to see what was in it," said Xu. "It was obvious that for all these years, that Hong Kong buyer had never bothered to open any of the bundles, let alone the scrolls."

"For my colleague, it was a gamble. He would win big if there's just one piece inside that bundle that was painted by a master," he says.

Xu says the closest contact he's ever had with a master painting was not long after he joined the Henan store, at the age of 22, having just completed his service in the army. "They asked me to learn how to mount traditional Chinese ink-and-brush paintings, a job that I thought was boring. But I learned nonetheless and the first painting I did was by Wu Changshuo (1844-1927), an undisputable master whose paintings routinely sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars today," says Xu. "After having it mounted, I hung it on the wall, and admired it from a few steps away. That's when a buyer from Japan came in. He looked around the four walls before going directly to the painting. 'This one, please,' he said."

"Because Wu was born relatively late, at the time the painting was sold, in the early 1980s, his works were not rated as national treasures," says Xu. "Even today, I ask myself: Where is the painting? It's my only hope that our future generations will not have to ask that question."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

| China's booming antique market has given birth to a gigantic army of collectors and traders among its own citizens. Provided to China Daily |

| Xu Qing (right), 56, has been working at the Henan Provincial Antiques Store since 22. |

(China Daily European Weekly 06/05/2015 page24)

Today's Top News

- Japan tempting fate if it interferes in the situation of Taiwan Strait

- Stable trade ties benefit China, US

- Experts advocate increasing scope of BRI to include soft power sectors

- New engine powers cargo drone expansion

- China to boost green industry cooperation

- Manufacturing PMI rises in November