Growing pains of an 'aunt' army

China's multitude of domestic service workers experience modern problems despite attempts to find market solutions

在中国的都市家庭中,阿姨变得供不应求,但这个行业的成熟程度还远远赶不上它的扩张速度

Stuffing her backpack with cleaning materials, Lu Shuping, 45, leaves her home at the edge of Beijing, heading to her first appointment of the day at 8 am.

It takes at least two hours and a bus transfer to get to her first customer's home. She wipes and washes meticulously for 25 yuan ($4; 3.7 euros) an hour, until the two-bedroom apartment is spotless, then rushes to do the same on the other side of the city. Lu's face is tanned and there are wrinkles at the corner of her eyes, but her bright eyes reveal a cheerful nature.

Many in Lu's position come from difficult circumstances; in her case, it was a gambling husband. Skipping out on his debts, he disappeared, leaving his job as a coalminer. Lu persuaded the mine to hire her as a replacement in order to earn a living. Today she is part of a burgeoning but sometimes troubled industry, that of the domestic service worker.

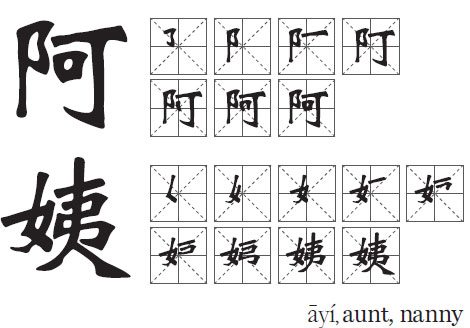

There are more than 22 million women like Lu across China working in the domestic service industry (家政服务). Primarily women from rural areas, they are called baomu (保姆, nanny), zhongdiangong (钟点工, hourly worker), or the more affable ayi, (阿姨) which means aunt.

In the 1990s, before the age of booming factories, salons and stores, domestic services was one of the few options for rural women in the city. Earning a few hundred yuan a month, they still took it as a good deal. Their employers, who trusted their nannies like family, would cover their food and accommodation.

This model is virtually extinct today. More jobs opened up for rural workers, and a domestic service industry grew with rising demand. In one sense, finding an ayi has never been easier, with agencies and, most recently, websites helping to match an ayi with a family. At the same time, there is a serious lack of industry standards.

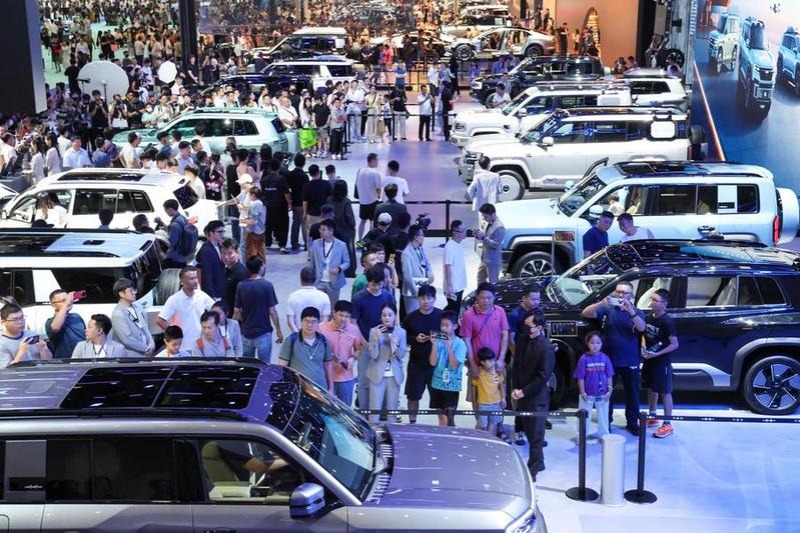

The demand for domestic service workers is at an all time high. People's Daily estimates that of the 190 million urban families in China, 15 percent require domestic service in order to function, and Beijing alone needs more than 1.5 million such workers. This is largely due to drastic changes in the Chinese family structure. Before the 1950s, a Chinese family consisted of 5.3 members on average, a report last year said the number had shrunk to 3.02. With the country's family planning policy, urban migration and lifestyle changes, the extended, multigenerational family has almost died out. This means less help within the family, especially in caring for young and old. With both spouses working full time and an emphasis on quality of life, a typical urban family requires a lot of help at home.

However, many clients say finding the right ayi is difficult. "It's so hard to meet a good one. Once you find her, you want to treat her like a goddess," says Hu Yang of Hangzhou. Hu went through 13 prospects in three years. "The first ayi bailed on me after only a month; another ayi broke our 3,000 yuan stereo while cleaning and left a week later because she found out that she was pregnant. From then on we were afraid to hire anyone under 50."

Hu also says there were cultural problems. "She would drink the leftover milk directly from the baby bottle and feed my baby food that she chewed in her mouth. I told her it was unhygienic, but she insisted that was how babies were raised in her hometown.

"We finally gave up and just wanted an ayi to help with cleaning, but the ayi we hired threw everything into the washing machine at the same time, including baby clothes, adult clothes and dirty cleaning towels. She just refused to change her ways."

Another problem is a lack of security for both parties. This year, a woman in Wenzhou hired an ayi who fell and broke her right hand on the fifth day of work. The employer covered the medical bills, but the ayi claimed she lost her ability to work and sued. After almost four months in court, the ayi got 29,900 yuan including medical bills, only 30 percent of her projected losses. For the employer, it was a colossal expense and headache. Such cases are common.

Some are striving to find a solution. Beijing Fuping Domestic Service Center is a pioneer. Fuping (富平) means to bring wealth to the common people. Founded by economist Mao Yushi and former Asian Development Bank chief economist Tang Min in 2002, the NGO works to train rural women aged 16 to 50 to be professional service workers and help them to find jobs in Beijing.

The Fuping school offers two to three weeks' of training along with food and accommodation at no cost to trainees. In its classroom, resembling a kitchen or a bedroom, many trainees experience an urban home for the first time. Besides housekeeping, the school also teaches basic nutrition, safety, medical and legal issues, communication skills and environmental awareness. Fuping's six offices in central Beijing help these women find employers and provide counseling and home visits.

Though Fuping is respected in the industry today, it, too, has had its woes. In 2006, an ayi was hired to look after a two-year-old girl. The woman left her on the sofa to pick up the laundry in another room, and the girl fell to the floor, hit her head and died. The family sued Fuping for almost 500,000 yuan. The case almost sank the small, struggling NGO. But it led to the birth of the standard industry liability insurance.

By last June, Fuping trained and helped 27,000 domestic service workers to serve more than 13,000 families in Beijing. Many of these women thrived and went on to pursue other careers.

Chen Junxia, 28, is one of them. In her ninth year in Beijing, she has recently opened a yoga studio. At her home in Gansu province, she had dropped out of school since her family was too poor to support her. "I shed many tears and had to work in the fields to help my parents," Chen recalls. Then she heard about Fuping's program.

After Chen finished her training, she got her first job as an ayi and was paid 800 yuan a month. In the years to come, she got married, become pregnant and quit her job. When her baby was 10 months old, she sent him back to her hometown and returned to work. Fuping helped her find another job, and she worked her way up and decided to start her own business. "Though I am not an ayi anymore, I still attend Fuping's various activities on the weekends, and it will always be my home."

Chen plans to get her son back to Beijing now that she can afford it.

Still, the efforts of a few NGOs are not enough. The healthy development of the industry is the real solution. Domestic service has now joined with e-commerce, and families can turn to the Internet or apps to find domestic workers. Big players in the field right now are Ejiajie (e-house clean), Ayibang (ayi helps), Ayilaile (here comes ayi), and Yunjiazheng (cloud domestic service).

Ayibang, for example, hires domestic workers and pays them a monthly salary with insurance, benefits and holidays, while customers pay the company.

Lu is one of Ayibang's recent hires. Hailing from a village in Shanxi province, she began her career as a domestic servant last July. She is already one of the company's highest earners, with a monthly salary of about 5,000 yuan. "I am very quick and thorough," she says.

"I quite like my job now," Lu says. "I work only eight hours a day, and sometimes when I finish early, I enjoy a walk in the park. ... As to the future, I don't worry too much. It can't be worse than before."

Still the lot of most domestic workers is a tough one. Slowly the market and customers are trying to get a better class of ayi by being a better class of customer, giving these essential people the respect, the money, and the safety they deserve.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 06/05/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

- Japan tempting fate if it interferes in the situation of Taiwan Strait

- Stable trade ties benefit China, US

- Experts advocate increasing scope of BRI to include soft power sectors

- New engine powers cargo drone expansion

- China to boost green industry cooperation

- Manufacturing PMI rises in November