Big, weird and oh so Chinese

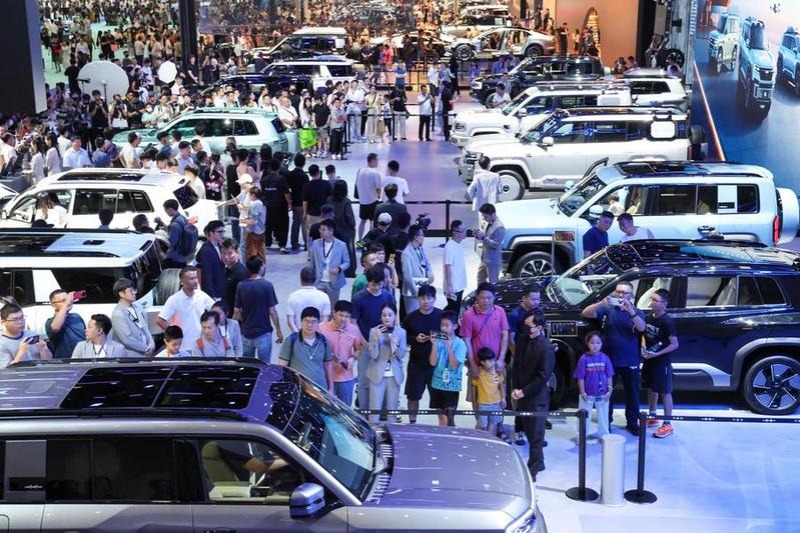

The country is showing the world a thing or two with its architecture

After several years of planning, a massive workforce began building Tianjin West Railway Station in early 2009. With the efforts of several thousand laborers, the vast 179,000 square-meter station was finished within two years.

Like some of the trains that pass through on the 24 lines beneath the station's barrel-vault roof, the construction process was a high- speed affair, even though the previous train station, a historic brick German edifice built in 1910, had to be moved to a location a few hundred meters south.

Construction of such a huge building so quickly would be an incredibly difficult undertaking in the West, but in China it is a frequent occurrence.

Sebastian Linack, one of the architects who worked on the design, says one thing that made it possible was the size of the labor force, which would be prohibitively expensive in developed countries. He also says China's experience with huge construction projects in recent years means it now has the expertise to handle projects of such magnitude.

This is one effect the construction boom has had on China's architecture. But even as it prompts the creation of new technologies and methods of construction, it has also spawned copycat monuments, cookie-cutter neighborhoods, immense skyscrapers, corruption, scandals and more than a few unusual buildings.

In Changsha, Hunan province, lie the seeds of Sky City, which was meant to be the world's tallest building. After being prefabricated on the construction site it was to be built in just 90 days in 2013. The initial plan by the architects and the developer, a subsidiary of the Broad Group, suggested a 666-meter-tall building, but local government officials, eager to have the world's tallest building, suggested bumping it up to 838 meters, thus beating the 829-meter-tall Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Officially the project is still on the books. But apart from about a month of construction activity on the site in 2013, nothing has happened since officials decided the project needed additional approvals. The site is now covered with water and a smattering of melon and corn crops. Sky City seems to be one of many projects that have succumbed to China's rough-and-tumble approach to construction.

But that same approach is what bestowed fame upon the Broad Group and its founder, Zhang Yue, giving them the potential to revolutionize construction and architecture. The company's primary focus is expensive air-conditioning systems that use natural gas and waste heat, which have proven popular in China because of constraints with the electrical grid, a consequence of such a rapid construction boom.

This income source has transformed Zhang and the company into a fierce proponent of tougher environmental standards, which in turn have spawned a subsidiary company specializing in prefabricated buildings erected at an impressive pace.

In 2010 the company built the 15-storey Ark Hotel, also in Changsha, in just six days, with the structural framework erected in less than two of those days. Admittedly, the groundwork and foundations had already been laid. But it remains an impressive achievement, particularly given that it used a fraction of the materials used in standard buildings and is said to be earthquake resistant.

Perhaps this technology will help remedy the style of construction typically used for residential buildings in China, with state media acknowledging the tremendous waste of concrete in buildings that usually last for only 20 to 30 years, and that on rare occasions have cracked or collapsed.

Higher-quality methods of rapid construction are no doubt needed, given China's still-frenetic pace of construction, which continues on a scale far too vast for architects or policy-makers to adequately compensate.

John Van de Water, a Dutch architect with extensive experience in China, describes the approach to architecture in China using "the rule of 10x10x10". "It's 10 times faster, 10 times cheaper and 10 times larger," he says.

"This is very difficult for most Western architects to understand." Architecture in China "requires a different approach", and you "have to design more strategically", he says.

In his book You Can't Change China, China Changes You he talks of occasions in which architects had to adapt their plans during the design process.

"Whereas in Europe it is more about a shared information process, here it has a more serial basis. If requirements change, the project is changed, and the architect may not be involved with that."

He also talks of how, in China, clients exercise a great deal of power over a project and like to have multiple options.

The boom has affected cities in different ways. "Some first-tier cities, like Beijing and Shanghai, were already blessed with an identity. But, second- and third-tier cities are on a quest for identity, and sometimes their construction projects can come across as very superficial. Their modernization process was more derived from Western ideas and less from traditional."

Sometimes these Western ideas come across in a very literal way. Entire neighborhoods have been copied from Western designs. Near the southern city of Huizhou lies an Austrian village. There is a Thames Town near Shanghai, and the country has more than one Times Square, and a large one is on the drawing board for Tianjin. Buildings with elements copied off the White House or Capitol Hill in Washington can be found all over China.

Huaxi, a village in Jiangsu province in which wealth has soared in the past few decades, now claims to be China's richest village. It has its own version of an Arc de Triomphe, not to mention a narrower version of the Sydney Opera House. However, the village has not just copied from overseas, boasting its own Tian'anmen Square.

Perhaps the most egregious example of copying, due to its sheer opulence, is the office building of the state-owned Harbin Pharmaceutical Group, which was built inside and out to be a replica of the Palace of Versailles near Paris, complete with gold-tinted carved walls, chandeliers, marble columns and mahogany furniture. Seemingly oblivious to both public perceptions and rudimentary irony, the company said it was built to promote culture and showcase "social responsibility".

But, that is not to say all the foreign design input has been so crudely handled. Van de Water says many second-tier cities are rapidly becoming more professional in their architecture and seeking designs that complement the local area. However, even when architects strain to integrate a project into the natural environment, it is a difficult path to navigate.

One of the better known recently built edifices in China is the 234-meter-tall building that serves as CCTV's headquarters in Beijing and which, because of its shape, cheeky Internet users have nicknamed Big Pants.

It was designed by the Pritzker Prize-winning Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas and drew attention from Chinese web users and media commentators when President Xi Jinping told a forum audience last October that China should not build "weird architecture".

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 05/01/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

- Japan tempting fate if it interferes in the situation of Taiwan Strait

- Stable trade ties benefit China, US

- Experts advocate increasing scope of BRI to include soft power sectors

- New engine powers cargo drone expansion

- China to boost green industry cooperation

- Manufacturing PMI rises in November