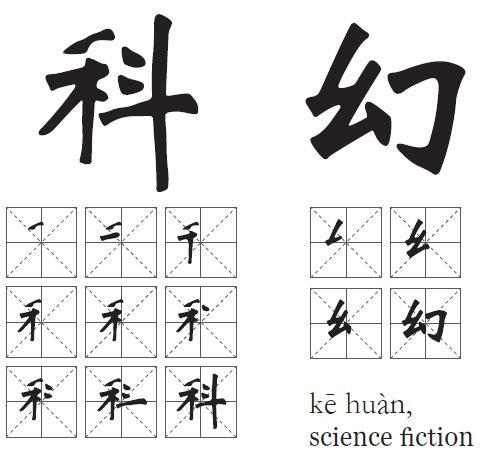

Sci-fi with socialist characteristics

Despite bouts of crippling suppression, Chinese authors over the years provided a glimpse of a better, future world

China has long worshipped science. But science fiction has been more slowly adopted. Fantasies of interplanetary travel go back millennia in China, but it was exposure to the outside world that drove Chinese sci-fi authors.

The technological superiority of the West posed serious challenges to the confidence of Chinese, some of which could best be answered in fictional form. Early 20th century Chinese science fiction fell into two categories. The first is the clearly satirical, like Lao She's (老舍) great Cat Country (《猫城记》), which tells of a voyage to Mars, where travelers discover an ancient civilization of cat people with suspicious similarities to China, or Xu Nianci's (徐念慈) Tales of Mr Braggadocio (《新法螺先生谭》). These are more akin to Gulliver's Travels than modern sci-fi.

The second are nationalist fantasies in which China re-emerges as a great power, defeating foreign invaders through technology. These works ironically mirrored the "Yellow Peril" fantasies once common in the West, in which an Asian power threatens the white man's rule.

The foundation of the People's Republic of China seemed to open up new possibilities for writers, though these mainly proved an illusion. Science occupied a special place in communist ideology. The initial wave of China's science fiction hit in the 1950s, at a time when science seemed to promise dreams of a glittering future and many Chinese scientists were returning to the motherland.

One of the most famous of the Chinese stories at that time was Zheng Wenguang's (郑文光) From the Earth to Mars (《从地球到火星》), the title some playful one-upmanship on Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon. It is a typical example of juvenile adventure as Spaceship No 1 rocketed to the Red Planet.

Zheng, like many science-fiction writers, was a scientist himself - an astronomer at the Beijing Observatory. He was well placed to bitterly observe the limits on science in a country ready to put ideology above reality, whether in copying Soviet pseudo-scientist Trofim Lysenko in genetics or in rejecting the very notion of expert knowledge. The "cultural revolution" (1966-76) ended science fiction in China.

The first tentative hints of change came in 1976, when Ye Yonglie (叶永烈), a then 36-year-old writer, published the first science fiction story in a decade and a half, Strange Cakes

(《石油蛋白》). The venue was Science for Juveniles (《少年科学》), still published today, one of the many popular magazines that survived by being focused on technological matters. Scientific magazines would give many sci-fi authors their first home, until a whole raft of specifically sci-fi magazines sprung up at the end of the 1970s.

From 1978 to 1983, China saw another brief golden age of science fiction, with millions of readers flocking to newsstands every month to enjoy their favorite authors. By Western standards, much of this seems clumsy and didactic - but then, so did most early Western science fiction.

Ye was easily the most dominant writer of the period, and the only one really still remembered by the public. His works tended to be hopeful; the most popular, selling over 3 million copies, was a series called Little Know-It-All Explores The Future (《小灵通漫游未来》).

In these, a Tintin-esque journalist, Xiao Lingtong ("Little Know-It-All") wanders about a China leaping into a new era of robots, artificial suns and other technological wonders. There's not much plot; they're more playful, aspirational inquiries into what could be. For Chinese readers for whom an electric kettle was still a luxury, they represented a world almost unbelievable.

There was plenty of nationalism on display in these works, too, with the focus often on peaceful scientific inventions turned to deadly ends. Thoughtful Chinese, like everyone else, were very much aware that the nuclear clock was close to midnight in the early 1980s. The bomb's shadow looms large in these tales of super-weapons and mass death.

Forty-three-year-old anthropologist Tong Enzheng (童恩正) won a national award for best short story in 1978 with his Death Ray on a Coral Island (《珊瑚岛上的死光》). In it, a Chinese scientist finds that his invention, a super-battery, can be turned to deadly ends by a foreign superpower, the "ASC" - implied to be a fusion of the Soviet Union and the United States - to fuel a death ray. The story was made into China's first science fiction film in 1980, now enjoyable largely as an exercise in accidental camp, especially the Chinese actors dressed in whiteface playing foreign villains.

Faintly menacing foreigners are a mainstay of the stories, especially those specifically aimed at kids, usually rival space expeditions or competing scientists, as in Wang Xiaoda's Mysterious Wave. Later critics tend to identify the antagonists as "American" - the actual nationality is rarely, if ever, stated - but in many cases the writers would have meant them to be read as Russians. The rivalry with the Soviet Union was far more acute, and the potential for real conflict far more alive in people's imaginations in the early 1980s. When Chinese contemplated nuclear annihilation, it was Soviet bombs they imagined.

It was Zhang, fresh out of the labor camp, who wrote some of the most interesting works from the time, mixing science fiction with literature about cultural revolution sufferings. In Mirror Image of Earth, aliens preserve the era's films as evidence of depravity.

The new generation had access to Western literature, fictional and otherwise. One of Ye's novels pays homage to journalist David Rorvik's 1978 book In His Image: The Cloning of a Man, where Rorvik claimed to have been involved in the successful cloning of a human.

Bizarrely, actual pseudo-science thrived in the 1980s, perhaps filling a gulf left by the disappearance of fiction. Alongside the science-fiction boom, a massive market for all manner of "extraordinary powers" supposedly preserved by qigong masters had emerged.

Mainstream newspapers wrote, without skepticism, of telepathy, telekinesis, karmic enlightenment, super-children, and miraculous healings. For years, until the field experienced its own crackdown in the late 1990s, Chinese newspapers were full of accounts that read like the wildest fantasy fiction.

Although some few science-fiction magazines limped on, the field was badly damaged. China's science-fiction dreams were put on hold. Eight years later, a new wave of writers would revitalize the field. But the brief spasms of inspiration from before give a vision, like much science fiction of the past, of what might have been in a better world.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 01/09/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

- Japan's PM seen as playing to right wing

- Mainland increases entry points for Taiwan compatriots

- China notifies Japan of import ban on aquatic products

- Envoy: Japan not qualified to bid for UN seat

- Deforestation is climate action's blind spot

- Japan unqualified for UN Security Council: Chinese envoy