From tiny beginnings

As growth in China's economy slows, a new approach is informing government thinking: small is beautiful

Sun Jia takes a sip of green tea, lights up a cigarette and leans back on the couch in the corner of his well-appointed first-floor office.

"They are the same ones President Xi Jinping used to smoke," he says with obvious pride, tapping a packet that has pictures of flowers emblazoned on it.

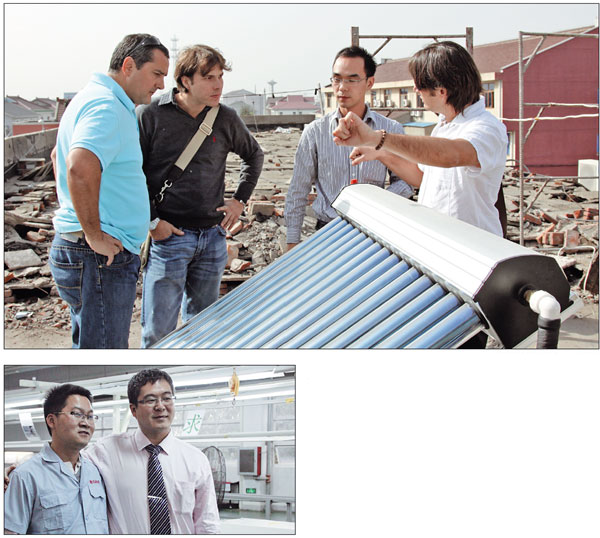

Sun is the general manager of Fuyav Energy Saving Appliances Co, a micro business in the southeastern city of Wuxi that specializes in solar water heating systems.

Fuyav, founded in 2009, is a lean running enterprise that manages to turn over about 30 million yuan ($4.9 million; 3.9 million euros) a year with a staff of just 10.

But that success is a newfound thing. Not so long ago, something as basic as three decent meals a day was a luxury well beyond Sun's reach.

And if the 34-year-old general manager seems keen to show off the trappings of his recent gains, it may be because they have been hard won.

In China, where the economic landscape is still largely dominated by state-owned behemoths, private business juggernauts and big multinationals, a rocky start is the common lot of micro companies and small to medium enterprises.

Many of these minnows of Chinese business also have a common fate, Sun says: failure.

A lack of access to finance, suffocating red tape, minefields of regulation and an almost ingrained cultural obsession with the notion of "big is better" means the odds have long been stacked against small businesses like Sun's in the world's second-largest economy.

But that defining characteristic of modern China, rapid change, is coming to the fore yet again.

And there have been many recent signs from the halls of power in Beijing, and from provincial and city level governments, that suggest some of the biggest political players in the country are backing a push for reform and regulatory overhaul that will benefit the smallest businesses.

The experts say a speech that Premier Li Keqiang gave in Tianjin in September is the clearest signal to date about why Chinese policymakers are now seriously committed to helping small businesses make the biggest impact possible.

China's biggest concern right now is not the slowing of economic growth, Li said, even though flagging GDP figures have the rest of the world fretting over what this will do to their economies. Instead, Li stressed that during its current phase of economic restructuring and reform, China's main preoccupation is in fact stability in workforce participation and job creation.

And promising results from some early reforms and far-sighted initiatives around China have shown that even in a slowing economy, SMEs and micro companies are punching above their weight, particularly in the key areas of employment and job creation.

As Li pointed out, nearly 10 million new urban jobs were created in China in the first eight months of this year, almost the entire yearly target.

And as Zhou Feng, a market financial analyst in Shanghai, pointed out in China Daily this month, Li acknowledged that the country's smaller businesses are contributing the most to this labor force stability. On the back of this, Li has hinted that smaller businesses will be given a further leg-up by reducing restrictions and increasing government approvals, a move that he believes will add to the country's prosperity. He is not alone in thinking this is the right course of action.

Chris Cheung, director of the EU SME Center in Beijing, believes the forecast fall in China's GDP growth to 7.4 percent this year, and even the predicted fall to between 6 and 7 percent by 2020, signals a positive maturation of the economy.

It is also good news for local and foreign SMEs and presents an opportunity for those keen to break into the mainland market.

"This is not a bad thing, especially for SMEs from the EU," he says. "Implied in the drop is the need for the Chinese economy to restructure itself away from export-led manufacturing, which has limitations on adding value to the economy ... toward a more sustainable model based on consumption and services being a greater part of GDP growth."

Professor Chi Renyong, dean of the Institute for SMEs at Zhejiang University of Technology, says China's long infatuation with rapid GDP growth is waning. He believes Li's focus on economic restructuring that will benefit smaller businesses is the right way to go, particularly if China wants to maintain or grow current employment levels.

"The recognition of the importance of SMEs and micro companies has increased in the past few years," he says. "In the past, governments focused more on big companies and paid very little attention to the smaller companies. But now we can see policy is changing, especially when Li says we need to promote and support the innovation of SMEs and micro companies.

"In the past our economic growth relied more on investment by the government and state-owned companies. Such projects promote the economy but provide little in the way of jobs, because they are mainly big infrastructure projects like road or bridge building. The current restructuring of the economy is designed to allow the government-spending dominated economy to make the transition to a market-dominated economy. It will make more creative companies active in the market, and companies that are less efficient and less profitable will be pushed out. In the long-term, a government-dominated economy is unsustainable. A market-driven one will create more jobs."

Chi says even though the contributions of SMEs and micro companies are often overshadowed by those of attention grabbing SOEs, the former already account for more than 95 percent of China's urban economy.

An initial round of reforms already introduced have paid dividends, he says.

The State Administration for Industry and Commerce says that between March and October about 2.5 million new businesses were registered in China, a 56.2 percent increase on the corresponding period last year.

The registered capital of these new companies totaled nearly 13 trillion yuan ($2.1 trillion), up 90 percent year-on-year.

"This is because the registration system has been overhauled recently," Chi says. "Unlike previously, you can now register a business with no capital and with greater flexibility about where you locate your business."

While it is difficult to predict how successful the strategy of improving the operating environment for smaller businesses in China will be, particularly if the aim is to ensure employment in a slowing economy, at least one precedent already indicates that wider reforms will bear fruit.

In the late 1980s, when China's economy was ramping up and almost exclusively dominated by big SOEs, Sun's hometown of Wuxi went a different route. Over the past 30 years it has made big changes specifically aimed at encouraging SME and micro enterprise growth.

Dai Kewei, the vice-director of the Wuxi Commission of Economy and Information's Small and Medium Enterprise Bureau, says the results speak for themselves, and the figures add credence to his view.

More than half the revenue the Wuxi government now receives in tax revenue is generated by SMEs and micro companies. The total take was 151.45 billion yuan last year.

These smaller businesses collectively also generated about 60 percent of the city's GDP of 807 billion yuan last year, and they account for 99 percent of all registered local businesses.

About 70 percent of the population employed in Wuxi, whose GDP grew 9.3 percent last year, work for small businesses, and the unemployment rate among its 6.2 million residents is a mere 2.12 percent.

"SMEs are the main force behind the economic transformation of this city," Dai says.

And viewed as a microcosm for the rest of China, the results in early adopter Wuxi suggest Li's train of thinking is on the right track.

Sun, for one, says his business is proof the initiatives are working. Without them, he says, his micro company would have gone belly up after the first year of operation.

Sun started the business in the nearby town of Nantong with two friends in 2009 using a hodgepodge of capital the three had scraped together. He borrowed his share, 300,000 yuan, from his parents and his uncle.

In the beginning, Sun slept on the floor of his workshop.

"The place I rented had very good ventilation, because there were holes in the walls," he jokes.

When the business lost 800,000 yuan in its first year, Sun's partners cut their losses and opted out.

"It was a very hard time," Sun recalls. "I was forced to become a vegetarian because I couldn't afford to eat meat. I couldn't get a loan from the bank in Nantong because mine is a small enterprise, and we didn't have any real estate or money to guarantee the loan.

"A lack of financing was my main problem."

Desperate but determined, he decided to relocate to his hometown, Wuxi.

It was a move that saved his business and allowed it to flourish.

Although securing finance is a struggle for SMEs almost everywhere in the world, Chi says the problem has long been exacerbated in China, where the big-is-better mentality has made state-owned banks reluctant to lend to small businesses.

This is despite China having an estimated 120 trillion yuan of financing in circulation, Chi says, with financing growing at an annual rate of 20 percent, outstripping that of the national economy.

"This shows that big companies still have a monopoly in the finance industry. Small companies must seek private financing with very high interest rates, which hinders their growth."

He believes this is now beginning to change.

In Wuxi, it already has. And the results there indicate easier access to finance will not only be a boon to startups and small companies wanting to expand, it will also increase employment and the overall performance of the wider economy.

"We recognized fundraising is the most difficult problem for SMEs and microenterprises," Dai says.

So Wuxi took steps to remove the obstacle.

Working in partnership with the Agricultural Bank of China, the city assesses the potential of commercial loan recipients on their patents and business model, instead of requiring capital and hard assets to borrow against.

For successful applicants, the city of Wuxi will then act as a guarantor, allowing the businesses access to the finance they need to start up or expand.

"The government has a budget (for this guarantor fund) of 100 million yuan a year," Dai says.

"All around China, the biggest problem for SMEs is to raise finance. According to our own figures, only 27 percent of SMEs receive finance from banks even here in Wuxi."

"But it's still a lot higher than elsewhere. In Xiamen (a city of comparable size) only 11 percent of SMEs receive finance from the banks."

"The government in Wuxi can make loan repayments for the SMEs if they don't have the money or liquidity at a certain time. We can greatly relieve the pressure on SMEs and reduce the risks for the banks."

Sun says it was the Wuxi government that stepped in, and seeing the potential in his business, interceded with the bank to help him get the finance he needed to get his operation off the ground.

Sunny Yang, president of solar power equipment manufacturer Long Max, similarly says his company would not be where it is today without the incentives the Wuxi government offered.

A manufacturer of power regulators for solar panel energy systems, Yang and three friends from university founded Long Max in 2002 with money borrowed from their parents. The Wuxi government subsidized their rent, provided tax incentives and helped them navigate the complex bureaucracy involved in registering a company.

But Yang, 36, says the biggest factor that made it possible for his company to get up and grow was the local relaxation of restrictive regulations, the same kind of regulations that have in part recently been adjusted in other parts of China, and that Li Keqiang seems keen to overhaul further.

"In Wuxi, we only needed 50,000 yuan in capital to meet the requirement for registration of a new business. At that time in the rest of China the minimum needed was 500,000 yuan in capital to register a business. In China, a company must rent or own a workspace to be registered. It's not like entrepreneurs in the West who can start at home or in a garage. Luckily the Wuxi government helped us find a workspace, too."

The company, which began with two employees, now has a staff of 130 and exports to several countries, including Germany and Australia.

Making his way through the hive of activity on the Long Max factory floor, Yang shouts over the crackle of welders and clanking of machinery.

"We started with nothing," he says. "Now our sales are worth 50 million yuan a year. We already have orders booked up until next July. Our workers are doing a lot of overtime, maybe working 10 hours a day now, and we're trying to hire more."

Chi, like Li, believes helping SMEs and micro companies will help China improve in terms of innovation, an area where it has sometimes struggled to compete with the West.

"Big companies pay more attention to market share and mass production," Chi says. "For small companies, often it's only innovation that allows them to survive, so they often have to develop new products or ways of doing things."

Sun says his business epitomizes this. Struggling to compete with large companies selling solar water heating systems, he approached the problem laterally and came up with an innovative new model that has allowed his business to survive and thrive.

"We used to simply sell our products to hospitals, schools and hotels. Now we build the systems, install them free of charge and continue to own the equipment. We just sell our clients the hot water our equipment makes. And it's working."

Another company that has thrived with the backing of the Wuxi government is Sen-Bio, a medical products manufacturer. Its chairman, Sheng Qingsong, says government support allowed the company to develop groundbreaking devices that can simply and efficiently detect lead and iodine levels in the human body.

"Chinese SMEs don't stand a chance if they choose to compete with the big guys here, or the big European and American companies. But if we focus on new areas we can own the market. They are often areas that require a lot of investment though, but have a lot of potential."

Wuxi has tapped into the potential of SMEs and micro companies through a process of investment and reform, says Dai of the Wuxi Commission of Economy and Information. He is uncertain about whether the same will happen in the rest of China, but with the rest of the country now also starting to see big changes for small business prospects, he thinks it may.

In Wuxi at least, from little things, big things continue to grow.

"Big enterprises provide a steady tax contribution, and some employment. SMEs and micro companies provide a lot of employment, and they are the big companies of the future."

Contact the writers through josephcatanzaro@chinadaily.com.cn

| Top: Sun Jia (second from right), general manager of Fuyav Energy Saving Appliances Co, a micro business in Wuxi that specializes in solar water heating systems, talks with clients. Above: Sunny Yang (right), president of solar power equipment manufacturer Long Max, with his colleague, Wang Yong, at the factory. Photos Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 11/14/2014 page6)

Today's Top News

- Japan tempting fate if it interferes in the situation of Taiwan Strait

- Stable trade ties benefit China, US

- Experts advocate increasing scope of BRI to include soft power sectors

- New engine powers cargo drone expansion

- China to boost green industry cooperation

- Manufacturing PMI rises in November