Six years that shaped a master of arts

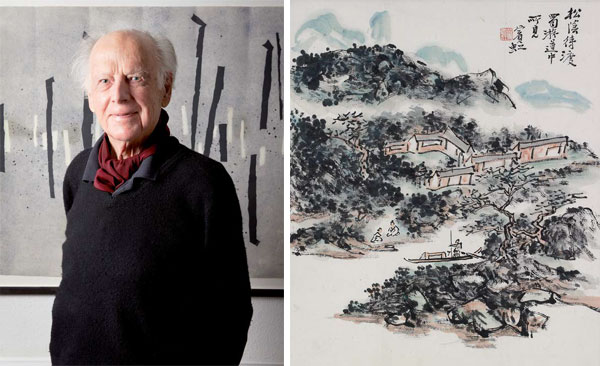

| Left: Art historian Michael Sullivan. Right: Waiting for the ferry in Sichuan by Huang Binhong. Provided to China Daily |

Exhibition portrays career of art historian who became a lifelong friend of Chinese artists

Visitors to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford can now admire what is hailed as the biggest private collection of modern Chinese art in the West. The art historian Michael Sullivan spent a lifetime building the collection and bequeathed it to the museum when he died aged 96 last year.

The collection includes more than 400 pieces, more than 100 of which had never been shown to the public before.

Visitors can also look into the extraordinary life of Sullivan, who developed deep and lifelong friendships with many late 20th and 21st century Chinese artists including Zhang Daqian (1899-1983), Huang Binhong (1865-1955) and Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), whose works are represented in his collection.

Shelagh Vainker, curator of Chinese Art at Ashmolean Museum, says Sullivan's friendship with Chinese artists is shown in the exhibition through letters and other forms of correspondence between Sullivan and his friends placed next to paintings.

In addition, some of the artists also dedicated their works to Sullivan and his wife Khoan, who died in 2003. It is appropriate that the first exhibition curated from the Sullivan collection is subtitled "A Life of Art and Friendship".

"The idea is to show that, over a long period, Michael was in touch with people in China, from the 1940s right to the end of his life," Vainker says.

The exhibition, which consists of about 40 works, will be shown until September, after which the paintings will be stored for a period of rest in order to maintain their quality, and other paintings from the Sullivan collection will be shown.

Sullivan was born in Toronto in 1916, and moved to Britain at the age of 3 with his family. After graduating from the University of Cambridge in 1939, he left for China to drive trucks for the International Red Cross.

He lived in China for six years. In 1942 he settled in Chengdu, working in a museum, where he was introduced to Chinese painting by the Paris-trained painter Pang Xunqin (1906-1985). In 1943, he married Wu Baohuan, a bacteriologist, who became known as Khoan Sullivan.

Vainker says this period of Sullivan's stay in China deeply influenced his life.

"He went to China as a conscious pacifist. He worked for the Red Cross as a way of helping with the war, but not fighting. He liked the country, he met Khoan and became familiar with Chinese art. So when he left the country, he trained formally in Chinese art."

In 1946 Michael and Khoan returned to London and he began his formal study of the language, history and art of China at the School of Oriental and African Studies, and later moved to the United States and completed his PhD in 1952. He then embarked on an academic career, first in the US, and moved to Oxford in 1984.

Over the years, Sullivan kept in touch with many Chinese artists. The many gifts of art he received inspired him to start a collection of Chinese art. Many artists appearing in his collection made a great contribution to revolutionizing Chinese painting and bridging Eastern and Western aesthetics.

One example is Wu Guanzhong, whose sensibilities moved easily between Chinese and Western media. He studied at what is now the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou and later at the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Such experiences allowed Wu to create a new and contemporary style of ink painting that captures the beauty of landscapes in striking simplicity. This can be seen in a landscape scene painted in 1973 and given as a gift to the Sullivans in 1980, called Wuxi and Lake Tai.

Vainker says Wuxi and Lake Tai is a wonderful piece - it is a painting of a Chinese landscape but using Western oil painting techniques.

"It closely fits Michael's own contribution to Western and Eastern understanding of art."

Another example is Huang Binhong, one of the last innovators in the literati style of painting, who was noted for his freehand landscapes.

This painting style can be seen in a landscape of Sichuan province, titled Waiting for the ferry in Sichuan, which Huang painted in the early 1930s when he was on a sketching tour in the province.

The painting shows some freely drawn outlines of cottages and plantations in the background, and a ferry in the foreground. Despite the painting technique's simplicity, the scene is characterized by beauty and calmness.

In addition to the paintings are many letters and other keepsakes that show Sullivan's deep relationship with his Chinese artist friends.

One item is a menu for a dinner in 1980, when Sullivan was invited by the Chinese Artists' Association to visit China, which was signed by Sullivan's Chinese artist friends, a number of whom he had not seen for 34 years.

There is also a letter that artist Pang Xunqin wrote to Sullivan to accompany a painting given to him. The painting, titled Tang Dancing Girl, was among a series of traditional baimiao line drawings he made in the 1940s. Baimiao is a Chinese traditional brush technique that produces a finely controlled, supple ink outline drawing.

Some of the paintings and letters were addressed to Khoan, particularly from Zhang Daqian. The Sullivans' friendship with Zhang developed after the couple moved to California in 1966 when Michael Sullivan was appointed professor of Chinese art at Stanford University.

In one case, a painting named Blue and Green Landscape, which was first exhibited at the Laky Gallery in California, drew Khoan's admiration. Zhang heard about this and sent the painting to Khoan as a gift.

The exhibition also includes other works of art, including ceramic sculptures, calligraphy and furniture. They include a fish ceramic sculpture by Ju Ming (born 1938). It was given to the Sullivans in 1991 and hung in their flat for many years.

Judging by the Chinese artists' generous gifts to Sullivan and their correspondence with him, Vainker says, "they must have had a good feeling about him".

Vainker says Sullivan was a charming person. "He was warm to people and fun. I think he was amazing."

Looking back at Sullivan's extraordinary life, Vainker says it was rare for someone of his generation to go to China in his early 20s, and even more unusual to live for six years and to come back with a Chinese wife.

"Usually men of his background and education would get quite a straightforward job in Britain or the US. Sullivan had his own ideas and independent spirit," Vainker says.

Sullivan's life as a teacher, writer, traveler and collector was celebrated with the exhibition Michael Sullivan and Twentieth-Century Chinese Art at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing in 2012, an event to which Vainker contributed.

"The theme was Michael's life as a scholar. We included letters and photographs of his time in China, and photos of him with various artists, and photographs of him throughout his career," Vainker says.

She says preparing for the Beijing exhibition made her better understand Sullivan's vast range of experience in many parts of the world.

"His perspective is never just the perspective of an Englishman. He lived and worked in China, London, the US and Singapore, and traveled to other countries in Southeast Asia. He had a truly international perspective. He was great at making friends and keeping in touch with his friends."

Perhaps it was Sullivan's international perspective that helped him to look into Chinese art at a time when it was barely noticed on the international stage. As early as 1959, Sullivan published a groundbreaking book, Chinese Art in the Twentieth Century.

Chinese art is becoming increasingly popular in the West, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London recently exhibited Masterpieces of Chinese Painting: 700-1900.

"I think it has a lot to do with the raised profile of China on the international stage," Vainker says. "People are more aware of China, and Chinese artists are more excited about working and exhibiting outside of China."

She is optimistic about this trend, adding that art is a good window into Chinese culture for the Western audience. "Visual things make a different impression, so it's an introduction to a different way of thinking."

Wang Shiyu contributed to this story.

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 05/23/2014 page29)

Today's Top News

- Takaichi must stop rubbing salt in wounds, retract Taiwan remarks

- Millions vie for civil service jobs

- Chinese landmark trade corridor handles over 5m TEUs

- China holds first national civil service exam since raising eligibility age cap

- Xi's article on CPC self-reform to be published

- Xi stresses improving long-term mechanisms for cyberspace governance